“As adults, we forget the empathy side of invention.” That’s just one of the nuggets I’m taking from The Henry Ford professional development courses I recently completed. They really got me thinking about how we as teachers can empower students as the next generation of innovators.

There are four courses currently available:

- Activating Your Innovative Mindset

- Becoming a Culturally Responsive Educator

- Engaging Students With Place-Based Learning

- Bringing Invention Education to Your Classroom

Each self-paced course takes about three hours to complete. Two of the courses are available at no cost (and if you’re a Michigan educator, you can get all of them for free!). You also get a certificate of completion that you may be able to use for clock hours or whatever the equivalent is where you work. That’s all great, but I’m recommending The Henry Ford professional development for bigger reasons:

It promotes student behaviors that are important for life as well as innovation.

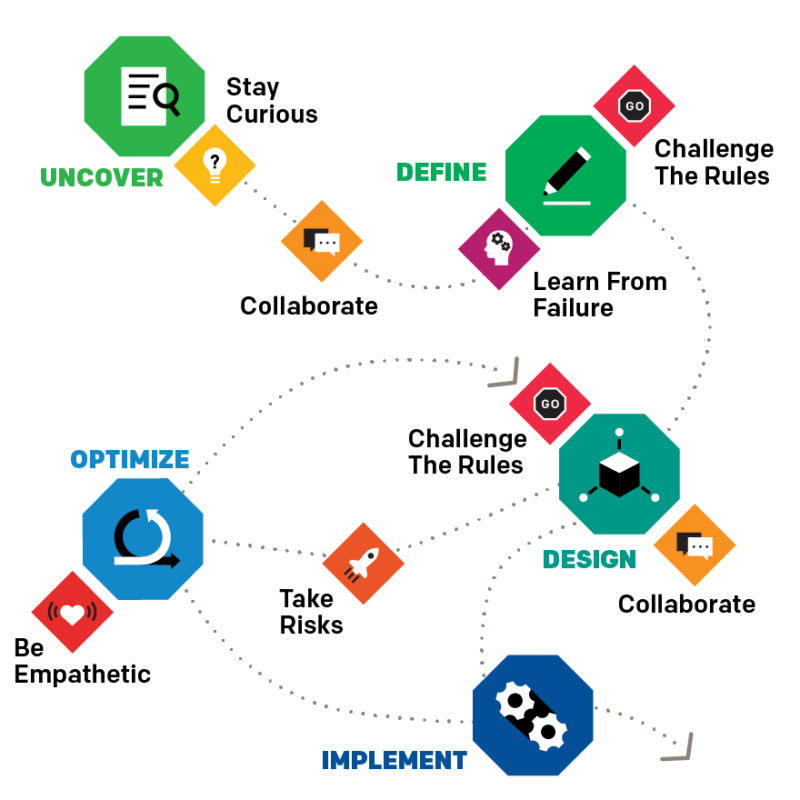

Model i is a framework that is unique to The Henry Ford, and it’s woven throughout their professional development. The framework is based on five actions and six habits that are common in stories of innovators, from the Wright Brothers to Rosa Parks. The actions and habits were designed to help unleash the inner innovator in all students, but what I love about them is they’re applicable to so many things. The path to innovation is anything but linear. Whether you’re creating something new, writing an essay, or solving a complex math problem, you engage in a similarly recursive process. Also, the “habits” are as important to everyday life as they are to innovation. As educators, we all want our students to collaborate, be empathetic, and learn from failure.

It encourages asset-based teaching.

For too long, education has operated under a deficit model, but that’s begun to shift. An important part of our own journeys of culturally responsive teaching is developing an awareness of inequity. These courses introduced me to the Innovation Atlas, a tool that helps you visualize the education and socioeconomic barriers that impact innovation. But while we work to remove barriers, we have to be careful not to view our students’ backgrounds as deficits. Instead, we need to harness them as the powerful tools they are with relevant content that reflects students’ realities and lived experiences.

Place-based learning is perfect for this. I really enjoyed the multiday instructional experience “Considering the Places We Know.” It invites students to consider how they inhabit both personal and collective spaces. They look at late-1800s photos by Jenny Young Chandler from the museum’s collection that have a strong “you are there” quality. The big ask from students is to take one photograph that, in their mind, captures their community in its truest form, the community that they know best.

It’s about empowering students and harnessing their natural empathy.

I just love that the messaging to students is that not only do their ideas matter, but they have the ability to bring their ideas to life. And really, the course content is about guiding students to develop the skills they need to do that. They might learn about the incredible life of Susana Allen Hunter and be inspired by how she challenged the rules of quilting through improvisation. They might work together to plan a hypothetical trip to the zoo. Or they might even consider a way they could help people and end up participating in the Invention Convention. In all of these examples, and the dozens throughout the courses and curriculum, students are building confidence in their own agency. And kids who care and believe in themselves are exactly the kind of people we as teachers want to send out in the world.