(WKBN/NEXSTAR) — Today, daylight saving time is associated with the twice-annual changing of the clocks. But, during a warring age when resources and money were scarce, daylight saving time was implemented in the hopes of cutting down the nation’s costs.

In March 1918, The Standard Time Act was passed by Congress, creating daylight saving time in the United States. President Woodrow Wilson signed the act into law, which then went into effect on March 31 as clocks jumped ahead an hour.

As reported at the time, the bill provision stated that at 2 a.m. on the last Sunday in March clocks nationwide that affect “any operations of the Federal government, or railroads,” would be set ahead by one hour. Then, come the last Sunday in October, they were to be set back one hour. (The bill also established time zones.)

The Washington Times reported at the time that the change was estimated to result in a $4 million cut in the nation’s bill for artificial light.

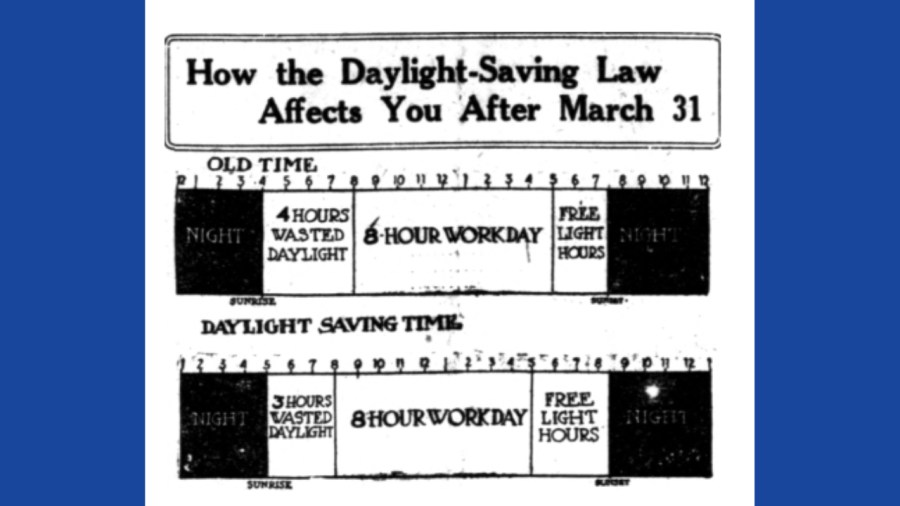

A March 16, 1918, volume of The Washington Herald advocated for the change, claiming it would give workers more hours of daylight that aren’t “wasted” sleeping or getting ready for work.

The article lists numerous benefits of the plan at the time, claiming it would increase food production, decrease traffic accidents, improve health, provide more fresh air, speed up freight transportation, add a shared hour of operations in the New York and London stock exchanges, allow for more time for “golf, amateur baseball and tennis,” give “women workers” the chance to “return from work in daylight,” and save approximately 1-1.5 million tons of coal per year — though it didn’t entirely elaborate on how these things would be impacted by the extra hour.

A representative from Pennsylvania told The Washington Herald that under the daylight saving plan, France had saved $10 million and Great Britain $12 million in fuel that would have been used in lighting.

While some praised the change, others were in opposition, especially Westerners and farmers, whose districts counted for most of the unfavorable votes.

“I once heard of Joshua ordering the sun to stand still three days — or hours — as a war measure. That must have been the first of the freak notions urged upon the people as war measures. I used to think my State legislature had the foolishest ideas in the world. But it never tried to change the sun in its orbit,” a Representative Thomas of Kentucky (presumably Rep. Robert Y. Thomas, Jr., though the report doesn’t clarify) told The Washington Herald.

The opposition seemingly won with the law being repealed one year later after the end of World War I. In 1942, during World War II, daylight saving time was reinstated as a fuel-conserving measure.

Three years later, it was again repealed as World War II ended, leaving individual states to establish their own standard time.

It wasn’t until 1966, when the the Uniform Time Act became law, that the biannual change became the standard that we still abide by today, despite recent failed attempts to observe daylight saving time year-round.

The U.S. did, briefly, observe daylight saving time permanently in the 1970s amid a national energy crisis. In an effort to extend daylight hours and cut back on the demand for energy, President Richard Nixon signed an emergency daylight saving time bill into law. There was great public support for the move, at least at first.

Among those who quickly lost interest in the change were parents, who found themselves sending their children to school under the shroud of winter darkness. (In some parts of the country, the sun wouldn’t rise until after 8 a.m.) Less than a year later, President Gerald Ford signed a bill to put the U.S. back on standard time through the winter, as we are today.

Daylight saving time ends on Sunday, November 3, and won’t restart until March 9, 2025.