The science of reading is a wide body of long-term, reputable research that has a lot to say about how kids learn to read and the most effective ways to teach them. The energetic discussion around this topic has a lot of districts all over the United States (even mega ones like New York City) looking carefully at the literacy curricula they use. How can you tell if the science of reading drives your curriculum? We’ve pulled together a checklist of best practices, red flags, and some reliable resources to help you evaluate specific programs.

Science of reading curriculum must-haves

There’s no one best reading curriculum for all kids that’s aligned to the science of reading (wouldn’t that be easy?), but reading research definitely points to some must-have curriculum components.

Phonemic awareness

Phonemic awareness is a kind of phonological awareness that includes isolating and working with spoken sounds. It is essential for pre- and early readers. It’s also often important to address gaps in this area with older, struggling readers.

Phonics instruction

Direct instruction in phonics—how to read and spell words—takes kids from spoken sounds to written language. A clear progression of phonics skills, and lots of chances to use them, is vital to any reading curriculum.

Content knowledge, vocabulary, and comprehension

Building kids’ knowledge of the world and what words mean enables them to understand (and learn from!) what they read.

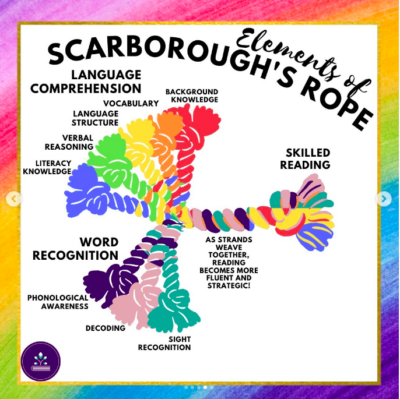

Instruction in all of these areas intertwines to move students toward skilled reading. Scarborough’s Reading Rope is a model to understand the interplay of all the skills needed for reading.

Source: @developingreadersacademy

Science of Reading–Approved Instructional Practices

The way we teach is just as important as what we teach. Research supports these practices:

Explicit, systematic instruction

Simply immersing children in reading, or teaching skills as they pop up, just won’t cut it for all kids. Directly teaching skills in a logical sequence works better. The National Institute for Literacy’s Put Reading First pamphlet is a good resource for understanding what explicit, systematic literacy instruction means.

Plenty of opportunities for “distributed practice” to achieve fluency

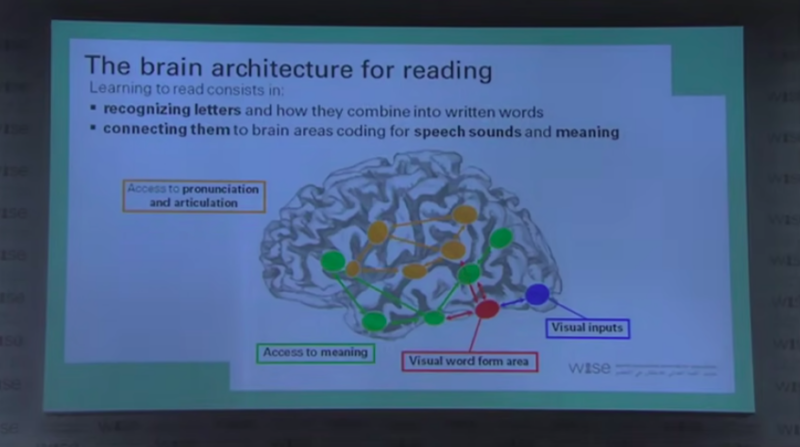

NWEA has a helpful guide for teachers about straightforward ways to align literacy instruction to the science of reading. One of their top tips is to make sure that whatever new skills kids learn, they have tons of chances for frequent, short bursts of practice over time. This frequent practice is what the brain needs to build connections between the different brain areas that are involved with fluent reading and writing.

Source: “How the Brain Learns To Read” by Stanislas Dehaene

Make connections to build knowledge

Rather than reading and writing about random topics, plan to use read-aloud material and writing assignments that continually build kids’ vocabulary and content area knowledge. Taking a close look at your science and social studies curricula and aiming for content overlap is a great first step here.

Use multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS)

MTSS is the practice of using assessment data in a proactive way to plan for the different levels of support kids may need. This includes support for English and multilingual learners.

Reading curriculum red flags and resources to use instead

Just like it’s important to look for key must-haves to tell whether the science of reading drives curriculum, it’s also wise to avoid resources that contradict the research that informs the science of reading. Some red flags are:

Cues encourage guessing at words.

Be wary of lessons that encourage kids to guess at words using the first letter, context, or what would “sound right,” without paying attention to all the letter sounds. This isn’t really reading, and it can lead to hard-to-break habits and stagnated progress. Instead, teach strategies related to using all letter sounds and also for monitoring comprehension. Literacy expert Nell Duke’s guidance on this topic is invaluable.

Reading material doesn’t reflect students’ skill learning.

Even if we do a great job teaching kids foundational skills, if the reading material we give them leaves them no choice but to guess at words, their chance for long-term success is limited. Consider decodable text, especially for early readers, and think carefully about the support students will need for tackling less-controlled text so they aren’t forced to guess.

There’s an emphasis on rote memorization of words.

Memorizing strings of letters without a focus on letter sounds just isn’t the optimal way for brains to learn. Learning to decode simple, phonetically regular words (like CVC words) helps students learn to connect letters and sounds when reading and writing. They can transfer this habit to learning irregular words (for example, some high-frequency words), even if they have to learn specifically about some of the unexpected ways sounds in those words are represented. The University of Florida Literacy Institute is a great place to start learning about teaching irregular words using strategies aligned with the science of reading.

Strategy and content teaching is piecemeal.

The best way to build content knowledge and vocabulary is to build a rich, connected picture of the world for kids over time. Using random passages, books, or writing assignments to teach a comprehension or craft strategies in isolation isn’t as reliable. Instead, consider using fiction and nonfiction reading material and writing assignments that relate to your social studies and science units, or otherwise build deep knowledge of a topic over time. Search our book lists for great titles on tons of topics.

Source: Fascinating Animal Books for Kids To Wow Your Readers

Science of Reading Curriculum Tools for Educators

Does your district mandate a certain curriculum that you want to do your homework on? Or are you in the market for new curriculum and don’t know where to start? There are reputable resources to help make your work easier.

Resources from The Reading League

The Reading League is a national education nonprofit aimed at sharing scientifically based information about teaching reading. Download their free Science of Reading: Defining Guide to build your own background knowledge about the science of reading to help you evaluate your curriculum. Also check out their Curriculum Evaluation Guidelines. They include a free downloadable workbook to help you look through your curriculum in detail.

Curriculum ratings from EdReports

EdReports is an independent nonprofit that evaluates and reviews instructional materials. The English Language Arts curriculum ratings score curricula for standards alignment and usability. High scores here aren’t the only data points you’ll want, but the reports do give helpful guidance.

Institute of Education Sciences (IES) Rubric for Evaluating Reading/Language Arts Instructional Materials

This rubric was developed for the Florida Department of Education but can be useful for everyone. It helps users evaluate K-5 literacy curriculum materials, including intervention materials. It weaves in recommendations from the What Works Clearinghouse practice guides. (This is another resource to bookmark!)

What is your favorite science of reading curriculum resource? Tell us about it in the comments!

Want more articles like this? Be sure to subscribe to our newsletters.