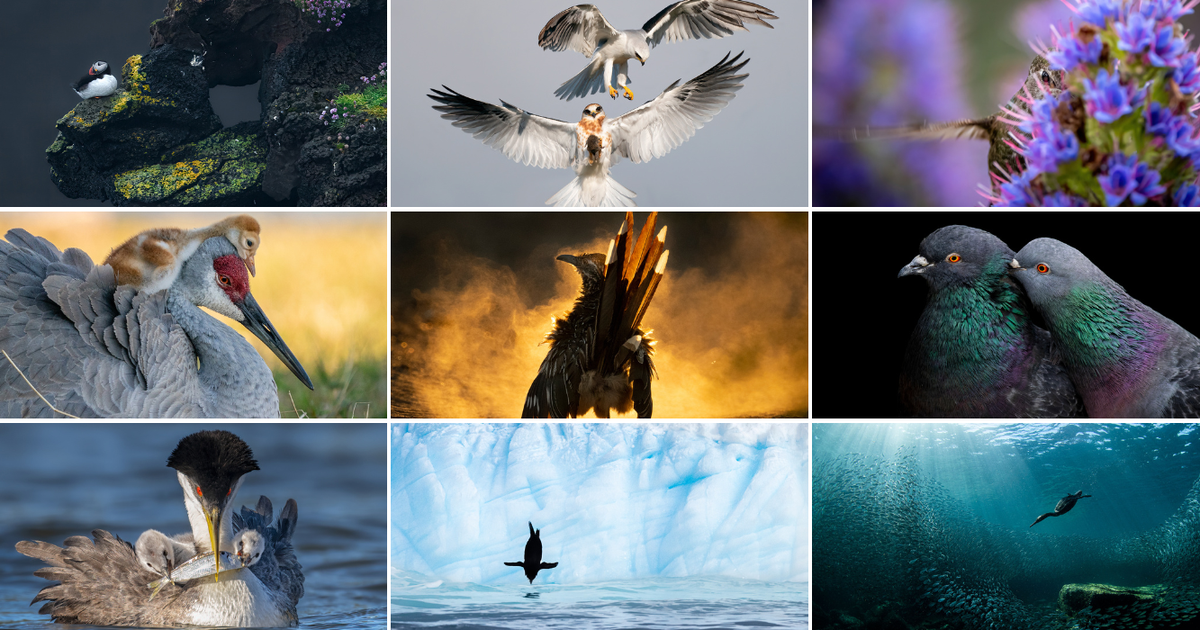

Each year we receive thousands of entries to the Audubon Photography Awards (APAs) that depict the beauty and behavior of birds around the world. But what does it take to stand out among the photographs? What are our judges looking for when deciding the winners of each competition?

To find out, we spoke with conservation photographer and judge Morgan Heim on Instagram. We covered editing tips and ethical bird photography. Heim also shared what photographers should be thinking about when submitting photos for consideration for our various prizes, including our new Birds In Landscapes Prize. From smartphone photography advice to ideas for getting that creative shot, we touched on the various ways photographers can wow the judges with their photos.

Read on for a curated version of the conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, and then watch the entire interview at the end.

And if you’re feeling inspired to submit your photos and videos to the 2024 Audubon Photography Awards, enter them by February 28 at 12 p.m. (noon) EST.

What are you looking for in a photo submitted to the Audubon Photography Awards?

There are three main things that I’m personally looking for, which are: you want it to be technically good. The other thing is that we want these photographs to be ethically made. We try to catch everything we possibly can so [photographers need to] adhere to strong ethical standards. And then the third thing is that there has to be something special about it. You need a moment—you need a cool behavior, maybe something we haven’t seen before. It doesn’t mean that it has to be an exotic bird. A lot of the most amazing pictures that we get in the competition that blow us away come from these everyday birds that [aren’t] photographed a whole lot. But when we do see photographs of them, [we know] someone paid attention and noticed an extraordinary behavior happening. Because we get to see them so much, you get to [notice] more behavior with these everyday birds.

Could you dive deeper into some of the elements that contribute to an award-winning bird photo?

We see a lot of technically great photos in this competition. And it’s the technical part I think that’s actually the easiest thing to learn as a photographer. Take a hard look at your photographs. You want to be thinking about composition. There’s all these rules—[you want to use] the rule of thirds and you want your pictures to be well-lit and well-framed. But we have to go beyond that for these competitions because there are many talented photographers out there. We’re looking for things like gestures, something that has an emotive sense to either the action that’s taking place or the way that the light is falling across the scene. That doesn’t mean that the bird has to be this big frame-filling [subject]. Some of the pictures that we got the most excited about last year were ones with this small, vulnerable-looking bird and this big, gorgeous landscape. There’s a different sense that comes from that picture, where you start to read the scene and almost feel like you’re there watching it. You don’t need a big telephoto lens to get those shots.

There can be a difference between a glance and a pose. You can have a pose that’s nice. But then it’s that frame—where a slight cock of the head, or the way the light catches in the eye, or the way the bird is looking at the other bird in the frame—where all of a sudden, it’s like there’s a conversation happening between them. You don’t want to anthropomorphize, but you can tell that there’s a moment happening between those two individuals in the frame. Those are the kinds of things that we’re looking for: moments, emotion, technical prowess.

What are the best ways to make simple edits to bird photos?

If you have to spend 15, 20, or 30 minutes editing your photo, you’re probably diving a little too much in the weeds. And it might be an indication that the picture is not that strong to begin with because you’re having to do so much work on it. I advocate for making simple adjustments, rather than just working in brightness and contrast. I work in Lightroom, just for reference, but a lot of platforms have these same sliders. I’ll work with my lights, my darks, my shadows, and my blacks. I’ll work on them separately because they’re a little more nuanced. I might sometimes take that brush tool and make some selective adjustments on the subject just to help make it pop a little bit. You’re not creating a completely different sense of lighting to the scene. You’re just helping to create a little bit more dimensionality.

I also recommend rather than pushing saturation, to push vibrancy a little bit so it won’t look as crunchy crayon-ish with your colors. But you don’t want to remove any elements that were there. The whole point is that you’re representing what was there when you took the photo. The only thing that’s okay to remove is if you’ve got dust spots on your sensor or lens or something that doesn’t change what you were photographing.

Audubon has a set of ethical bird photography guidelines to adhere to. But what recommendations do you have for others to practice ethical bird photography in the field?

There are some general rules that are good to follow. One is to stay away from baiting. Don’t bait your animals, especially mice with owls. That’s the most popular thing that I think happens out there and is held up as an example. Don’t encroach on nests—you want to be very mindful of nesting birds. I think that one of the big things no matter how you’re photographing is to always be paying attention to bird behavior. Think about how they are reacting to you. Come in with as much knowledge as you can about the species you’re likely to see and how they’re using their spaces during a particular time of year. Raptors could be a lot more sensitive—or, say owls at a nesting hole—to human presence. If they’re watching you, they’re not looking for food. If you’re in the field where they want to go after prey, they’re not going to while you’re right there. But songbirds, on the other hand, are just manically going through the trees and going after all the berries and bugs. For a person standing in a field, they just don’t have time to pay you any mind when they’re doing that. Keep your distance, but they’re just going to keep doing their thing.

Always pay attention to how the bird is responding to your presence. If you see it spending a lot of time paying attention to you or shifting off its nest or acting disturbed, back away and create some distance, or give it a rest and come back later. Read the cues so that you’re being respectful to the animal that you’re photographing. We’re not just there to get a shot. We’re there to be respectful of the birds and to wonder at the fact that we get to share this planet with them. Anything that we can do to make sure that that continues to happen is more important than a cool photo.

Want more tips and guidance? Watch our full conversation with Morgan Heim below.