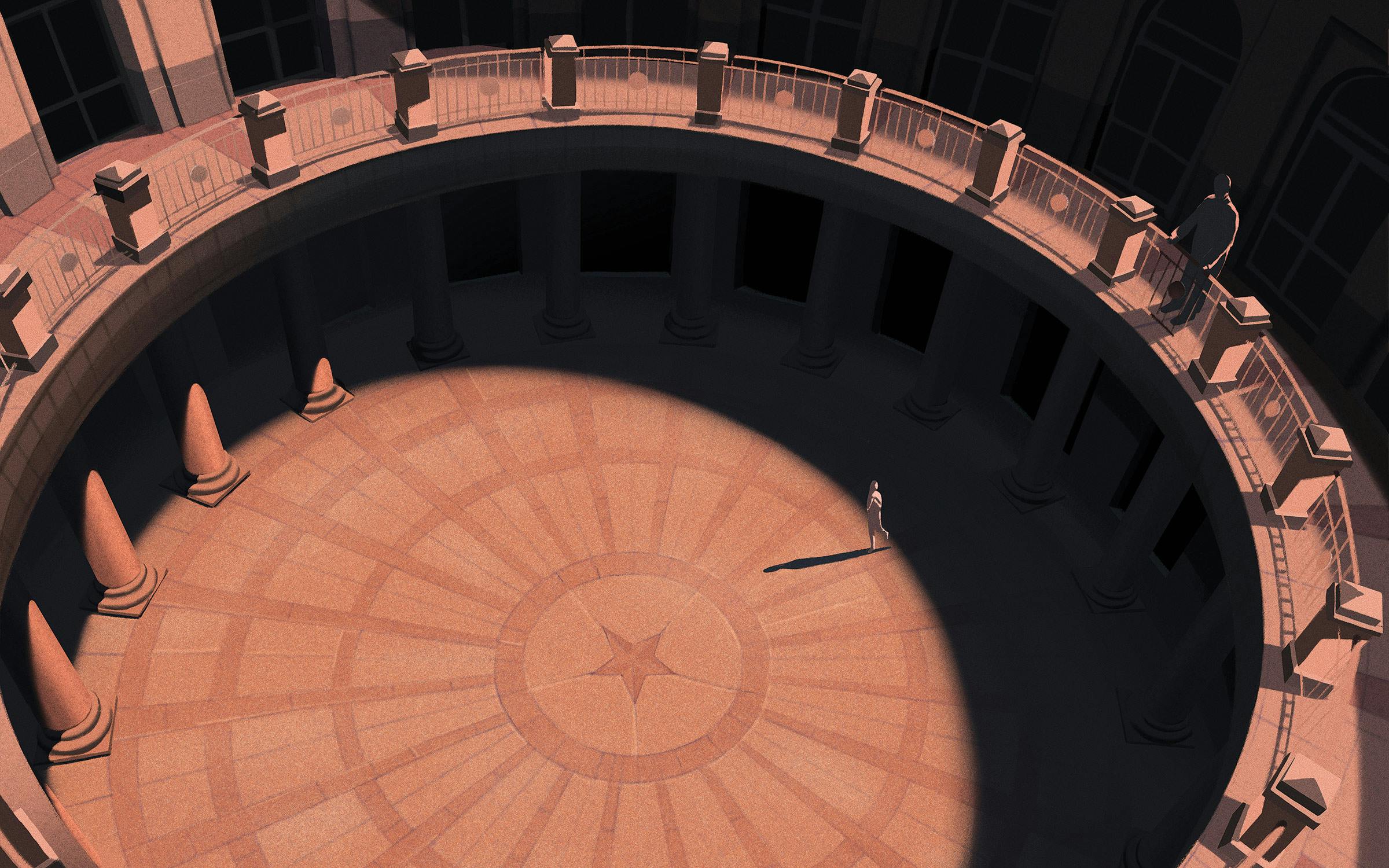

Lila had been working late again. Her ballet flats pattered on the terrazzo floors of the Texas Capitol as she walked through the bowels of the building, up the stairs, and out its heavy, carved oak doors. Across the expansive south lawn, a few blocks away, she joined some fellow Senate interns who were enjoying the evening at a bustling rooftop bar. She looked forward to relaxing with Moscow mules and tacos under the glow of the string lights overhead. It was a beautiful March evening—until it wasn’t.

A 21-year-old college senior, Lila worked for state senator José Menéndez, a San Antonio Democrat. Soon after sitting down with her friends, she started venting about the months of touching, after-hours texts, and questions about her dating life that she had been facing from the lawmaker’s 52-year-old chief of staff, Thomas “Tomas” Larralde. As she talked, her phone buzzed on the sticky high-top table. Larralde had sent an incoherent message to the office group chat—which included the district director and the senator. It appeared that Larralde, a brash and divisive figure, was drunk. If he’d spoken the jumbled words, Lila imagined they would’ve been slurred.

Someone else in the chat responded to ask if he was okay. Larralde didn’t reply, but five minutes later he sent a private message to Lila (who asked that we not use her real name, out of fear of retaliation). “How’s your night,” he texted.

“Pretty good! Nothing too crazy, yours?” Lila responded.

“I’ve been drinking,” he said. “So on a scale of 1 to 10. It’s a 5.”

As her phone lit up, the other interns looked on in horror at the behavior they were witnessing in real time. “I remember showing my friends,” Lila told Texas Monthly. “I was like, ‘This is exactly what I was talking about!’ ”

Soon Larralde, who did not respond to multiple requests for an interview or to specific questions about his time in Menéndez’s office, called her. Lila didn’t answer. Later that night, she parked in front of a friend’s one-bedroom apartment, where she’d been staying. She sat in her car for half an hour, thinking about how she would have to work with Larralde on Monday. “I could not physically move,” Lila recounted. “I felt really terrified at that point, too, of what was going to happen next.”

Around 10 p.m. on Sunday, Larralde texted again and asked about her weekend. He sent another message at 7:25 a.m. on Monday, on his way into the office. Lila tried to keep their interactions professional, but her anxiety persisted. One afternoon about a week later, she answered the office phone. An official with the San Antonio Police Department asked to speak with the senator about Larralde. Neither was in the office, so Lila promised to pass a message to Menéndez. She then opened Google, typed “tomas” and “san antonio police,” and saw the headline “Chief of staff for Sen. Jose Menendez faces DWI charge.” The date of his arrest was March 27, 2021.

She was startled at the sight of Larralde’s mug shot—head cocked to one side, brown eyes flanked by smirking smile lines, salt-and-pepper stubble dappling his chin. A San Antonio police officer found Larralde asleep behind the wheel of a parked, still-running vehicle with its headlights on in a San Antonio lot around 2:50 a.m., a few hours after he had been texting Lila as she ate tacos with her friends. The arrest report noted that his eyes were bloodshot and he smelled like alcohol.

“It made me feel so disgusted that he was essentially getting arrested but still thinking about me,” she recounted. Then she thought: the senator can’t ignore this. A week after the SAPD call, when things went back to business as usual in the office, Lila felt overwhelmed. She walked to the restroom, closed a stall door behind her, slid to the floor, and sobbed. She composed herself enough to find Pearl Cruz, Menéndez’s then–legislative director, and told her that Larralde was making her so uncomfortable that she couldn’t work. She explained how, during her second week on the job, Larralde had plopped down on the oxblood chesterfield next to her reception-area desk and asked if she had a boyfriend. She told Cruz how he’d stop by most mornings he was in Austin to ask for help putting on the wristband that indicated he’d tested negative for COVID-19, part of the Senate’s pandemic protocol. And she told Cruz about the late-night texts he’d sent.

Cruz asked to see the messages from Larralde, then sent Lila home. Lila sent Cruz screenshots when she followed up the next day. In interviews with Texas Monthly, the senator said he acted quickly, ordering Cruz to ask Patsy Spaw, the secretary of the Senate (the executive administrator of the upper chamber), “ ‘What is the fastest way possible to terminate someone without them ever coming back into the office?’ ” He recalled telling Cruz, “ ‘I want all the documents ready for me—and I want all the keys, key cards, everything turned off.’ ”

Menéndez decided to fire his chief of staff. “I was like, ‘Okay, this guy’s gone,’ ” he said. “It took less than twenty-four hours to get rid of him.”

Others in the Capitol, however, told Texas Monthly that he had known of Larralde’s misconduct for more than five years. By the time Lila came forward, three current and former statehouse employees had reported to Menéndez what they described as Larralde’s demeaning and sexist behavior, during incidents starting in 2015, Texas Monthly found. One former staffer said she repeatedly told the senator that she saw Larralde touch female colleagues inappropriately and also complained to Menéndez about the chief of staff’s lewd jokes. Another former staffer said she described Larralde’s conduct to Menéndez as flirtatious, creepy, and belittling. One former lawmaker told reporters she’d called out Larralde’s use of sexist language, and Menéndez had apologized for it.

When asked about these complaints, Menéndez told Texas Monthly that he did not believe they involved behavior constituting sexual harassment and that Larralde’s texts to Lila were the first proof he had seen. “ ‘Tomas was a real asshole today.’ Maybe I heard that a few times,” he said. “But nothing specific that crossed the line.” That said, the senator admitted that he’d threatened to fire his chief of staff in 2019 “due to his party atmosphere.”

The complaints Menéndez received were about behavior consistent with the examples of sexual harassment detailed in the Senate’s policy, including “sexually oriented comments, jokes, or gestures,” “messages that are sexually suggestive, or in any manner demeaning, intimidating, or insulting,” “unwelcome physical contact,” and “repeatedly asking a person to socialize during off-duty hours when the person has said no or has indicated that he or she is not interested.” Other staffers said they left Menéndez’s office in part because they didn’t feel comfortable working with a man they described as misogynistic.

Menéndez’s failure to view these complaints as reports of sexual harassment is emblematic of breakdowns in the enforcement of the Senate’s sexual harassment policy, which was updated in 2018 and trumpeted as a deterrent to misconduct in the Capitol. In practice, the new policy has functioned to protect individual senators accused of misbehavior and the reputation of the institution rather than the women who work there.

Lila had made a verbal complaint to a supervisor, as instructed in the policy, but there are no public records of her complaint or of any investigation into allegations of sexual harassment by Larralde, according to Spaw, who serves as the custodian of all Senate records. Menéndez confirmed to Texas Monthly that at his direction Larralde signed a nondisclosure agreement barring him from discussing the circumstances of his termination. Then, days after Larralde was fired, Lila’s internship coordinator called her and asked her to sign a document that Lila understood would have given the internship program “cover” by outlining steps it had taken to handle the situation. Lila never signed anything. “I kept saying, ‘No, I don’t want to sign it, I don’t feel comfortable signing it,’ ” Lila told Texas Monthly. “I felt very alone and taken advantage of. I don’t have an attorney.”

Nearly as soon as Lila spoke up, the allegations, and Larralde, disappeared. Larralde sent a goodbye email to the office announcing that he was going to focus on his family (he now works as an insurance agent). Many inside the Senate, including Lila, believed that the DWI arrest had prompted his ouster. After his departure, the San Antonio district attorney’s office declined to prosecute the charge against him, citing insufficient evidence.

It would be easy to see Larralde’s case as an isolated incident—and one that was eventually solved with his firing. Most Texas lawmakers and their staffers have never been publicly accused of sexual harassment. But in the macho culture of the Capitol, where some legislators have famously watched porn on iPads on the Senate floor and forcibly kissed journalists, Lila’s experience is hardly unique, and harassment remains widespread. During nearly twelve months of reporting and more than a hundred hours of interviews with current and former elected officials, legislative staffers, interns, and lobbyists, Texas Monthly reporters learned about new sexual-misconduct allegations against Senator Borris Miles, a Democrat from Houston; Senator Charles Schwertner, a Republican from Georgetown; and former senator Carlos Uresti, a Democrat from San Antonio. (None of the three responded to multiple interview requests or to specific questions we sent them about the allegations.) We also spoke with the woman at the center of a headline-grabbing 2018 Title IX complaint against Schwertner. She agreed to her first-ever interview about a lewd photo and text messages she says she received from the senator (which he has denied sending), in part because of lingering frustrations she felt over the investigation he thwarted by refusing to cooperate.

One accuser came forward by name for the first time. Others, like Lila, spoke only on the condition of anonymity because they fear retaliation and professional damage—outcomes some have experienced, witnessed, or heard about at the Legislature. (We verified their identities and corroborated their stories through interviews with current and former statehouse employees and contemporaneous records.) Several other women who work at the Capitol told us they had experienced sexual harassment but were unwilling to speak for this story, even anonymously, for fear of professional blowback.

Since the #MeToo movement went viral, in 2017, women have increasingly come forward about sexual harassment they’ve experienced in workplaces across the country, encouraged by signs that their complaints will spur change. Yet unlike other employers that have made progress toward zero-tolerance policies, leaders in the Texas Senate have created a system in which lawmakers who sexually harass employees, interns, and students—a state crime—are seldom held accountable. As a result of a lack of records, the public is left in the dark.

The Senate’s revised policy removed a clear instruction that anyone with knowledge of sexual harassment should report it directly to human resources and the secretary of the Senate. It now says employees may report misconduct to their supervisor or chief of staff or submit an internal complaint to the HR director or the Senate secretary. In practice, Texas Monthly has found, only reports made to the latter two individuals are treated as “official complaints” that trigger an immediate investigation, with the probe to be handled by the director of human resources and impartial attorneys. The 31 senators are given leeway to handle sexual harassment complaints reported to supervisors within their offices as they see fit. The policy does not require that senators keep any record of complaints, investigate those complaints, report those complaints to any central office in the Senate, or hold anyone accountable for misconduct.

At best, experts say, the wording of the policy is confusing. “You have to kind of read closely to realize that a complaint to your boss would resolve things in a more informal manner,” said Elizabeth Tippett, a professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Law who researches employment discrimination. “People might think this bigger process is involved, even though if you read it, you realize it’s different.” Letting individual senators or their staff investigate sexual harassment complaints makes it more difficult to demonstrate that the body has taken immediate and appropriate action on complaints, as required by state and federal law, said Robert E. Goodman Jr., a Dallas-based managing member of Kilgore Law who has litigated decades of employment cases in Texas.

What’s more, there’s no public accounting for how complaints have been handled. Multiple written requests to Spaw and to Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, the president of the Senate, for any records of sexual harassment complaints or investigations were met with similar answers: no responsive records. Requests for notes, emails, or other documentation from meetings,

discussions, or consultations involving questions of whether or not sexual harassment occurred elicited the same reply. Archivists with the Legislative Reference Library also said they had nothing.

When asked why his office didn’t turn over records of complaints, Patrick’s press secretary, Steven Aranyi, wrote, “Our office released no records because there are no records to release, as no complaints of sexual harassment have been filed with Lt. Gov. Patrick’s office.” In a statement to Texas Monthly, Spaw, who did not respond to multiple interview requests

but answered some written questions, acknowledged that she knew about Lila’s case. She wrote that she never “received and neither has Senate Human Resources received an official complaint regarding Senator Menendez’s office. It is my understanding that, as provided in the Senate policy, a matter was reported to and handled and resolved by the Senator, both expeditiously and appropriately.”

Spaw added that “no official sexual harassment complaints have been filed in the Senate since 2001,” an idea that Lisa Banks, an employment attorney and founding partner at D.C.-based law firm Katz Banks Kumin, called “utterly preposterous.” Banks represented Christine Blasey Ford when she testified to the U.S. Senate judiciary committee that Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her when they were high school students.

“The fact that they say that shows they have a problem,” she said. “The clear inference is they’re making an effort to not have anything in writing, to cover themselves.”

While the Texas House has recently demonstrated its policy’s efficacy by ousting a member accused of sexual misconduct, in the Senate it appears that multiple harassers have been given free passes. Jen Ramos, a political consultant who has worked in and around the Texas Capitol for seven years, contends that some senators continue to behave this way because no one has held them accountable. “They feel like gods in the building.”

Patsy Spaw is a key figure in the Senate’s handling of sexual harassment. A graduate of St. Edward’s University and the University of Texas School of Law, she has worked in the Senate for more than 55 consecutive years—23 in her current position—which is longer than any current senator’s tenure. On most days of a legislative session, she wears rimless glasses and a warm, confident smile as she oversees the chamber’s procedures and reads bills from her podium on the Senate floor, just in front of the lieutenant governor’s desk. She rarely takes breaks. Her resolve to stand through Wendy Davis’s historic eleven-hour filibuster of an abortion bill has become Capitol lore. “I’ve been working here a very long time, and I still love to come into this building every day,” Spaw told the Texas Tribune in 2019. “I feel privileged to work here.”

Behind the scenes, Spaw also serves as general counsel to the body and is responsible for its operational functions. According to the Senate website, she supervises the elected officers and department directors, including the head of human resources for the chamber. Most current and former Senate employees interviewed for this story describe her as the main arbiter—under the direction of Senate president Patrick—of policy regarding most personnel issues; many junior Senate employees said they didn’t even know how to contact human resources, let alone what its authority might be. Spaw denied this characterization and wrote that she was “not responsible for personnel issues” in each Senate office. She said those offices and Patrick’s were in charge of setting their own policies and procedures, and described them as “akin to 32 small agencies.”

When anyone in the building complains of harassment by senators or their staff, Spaw is hardly an impartial actor. “The Secretary must satisfy the demands of her electorate, the 31 members of the Senate,” according to the chamber’s official website. While Spaw is notionally responsible for reining in any misconduct by lawmakers, those same lawmakers have the power to replace her at the beginning of every session, when she must seek reappointment—a point that Patrick’s press secretary and Spaw both noted in their statements to Texas Monthly.

Some of those who have worked in the Senate say Spaw seems to see her role not as protecting female staffers but rather as protecting senators from temptation. They say she and her aides hold young women in the chamber responsible for not attracting undue male attention. Texas Monthly has found that Spaw employs a three-pronged approach to curbing harassment in the Senate: chide errant senators in private, aggressively police a rigid dress code among women working in the chamber, and remove from the floor any women who’ve repeatedly “distracted” lawmakers. Spaw has adopted the mantra of her predecessors: “No toes. No cleavage. No shoulders.”

Spaw and her deputies believed “girls distract boys,” according to a former Senate messenger. Rick DeLeon served from 2007 to 2021 as sergeant-at-arms (reporting to Spaw) and was tasked with enforcing the dress code.

Grace Gnasigamany, who worked as a messenger in 2017, told Texas Monthly that when she showed up for her final job interview in black dress pants and a navy blazer, DeLeon berated her for dressing “unprofessionally.” Pants, DeLeon told her, were off-limits for ladies. Bare legs and even tights—as opposed to pantyhose—were also forbidden. He drew a layout of the Senate chamber for her and explained how visible messengers were to the senators. “He said, ‘With the angle of where you sit when you’re on the floor, it’s easy to look up your skirt,’ ” Gnasigamany recalled. (She left the interview fuming, confused as to why she couldn’t just wear pants, then took to Snapchat to vent and saved the screenshots, which she shared with Texas Monthly.)

DeLeon did not respond to multiple requests for an interview and declined to respond to a list of detailed questions about his time in the Senate. One former messenger told Texas Monthly that DeLeon’s methods were outdated, but that she ultimately believed he had a big heart and was trying to protect her. She said DeLeon once pinched her legs in his office to make sure she was “in her uniform” of pantyhose.

Some women who tried to report sexual harassment, or watched their colleagues do so, learned quickly that they, and not their tormentors, would be the ones to face consequences. Kara, who worked under Spaw and DeLeon in 2017 as a 22-year-old, told Texas Monthly about her experience on the floor that session. (She chose a pseudonym to protect her identity, as she still works in state politics.)

Early in January of that year, in the bustling back hallway behind the floor of the upper chamber, then-senator Carlos Uresti, a Democrat from San Antonio, approached her. The middle-aged lawmaker with neatly styled black hair asked how old she was, where she liked to drink, and eventually if she had a boyfriend. Then, Kara said, he gave her a gold card with his contact information and said he’d love to take her out for a drink. Kara reported the interaction to DeLeon. A few days later, he told Kara he’d spoken to Spaw and it would be taken care of; Uresti shouldn’t be bothering her anymore. “I thought that was the end,” Kara said, “and the worst of it.”

It wasn’t. Shortly after, Kara said, Uresti confronted her in the same hallway, saying she could have told him she wasn’t interested and that she didn’t have to go to Spaw behind his back. Uresti, who did not respond to a request for an interview, resigned his office in 2018 after he was convicted of money laundering and wire fraud, and later was also convicted of conspiracy to commit bribery. He served four years in federal prison and now consults for a law firm in San Antonio.

For the remainder of Kara’s time in the Senate, she no longer felt comfortable reporting the harassment she continued to face. After talking about her experience with DeLeon, she says he confronted her multiple times that session about her attire in ways she found misogynistic and demeaning.

On a few occasions when DeLeon thought she might be wearing stockings instead of pantyhose, he asked women more senior to Kara to go with her to the bathroom to make her show them what was under her skirt, she said. Another time, on a particularly warm sixteen-hour workday, a colleague took off the cardigan she was wearing, so Kara, who believed her arms were supposed to be covered at all times, asked another colleague if it was okay to take off her sweater. When DeLeon saw her in a shirt with cap sleeves, revealing her arms, Kara said, he confronted her and called her a “hussy.” He lectured her about “how I had been showing myself off all session,” said Kara. “What he attacked wasn’t my work. It was me, my appearance.” Kara said she left to cry in the copy room, gathered herself, went back out, and did her job.

Within a few months, Kara was no longer assigned to spend time on the floor “because certain senators found it too distracting,” she says.

Another former colleague confirmed that DeLeon acted as if enforcing the dress code and moving Kara’s workspace were part of an effort to protect her, when instead those actions essentially penalized her. The colleague recounted, “Just because she did what they said, and just because she told them what was going on—that didn’t mean that it stopped.”

In the wake of reporting in 2017 by the Daily Beast and the Texas Tribune on sexual harassment at the statehouse, Dan Patrick tasked Senator Lois Kolkhorst, a Republican from Brenham, with reviewing the Senate’s sexual harassment policy. The policy amounted to just a handful of paragraphs at the very end of the 95-page employee handbook. It included examples of sexual harassment and instructions for those who’ve experienced or had knowledge of such behavior to report it to their supervisor, human resources, or the secretary of the Senate. In accordance with the policy, a complaint would prompt an immediate investigation.

That December, Spaw and human resources director Delicia Sams testified for more than an hour before Kolkhorst and four other members of the Senate Committee on Administration. While the hearing was open to the public, testimony was by invitation only. Spaw and Sams were the sole witnesses. The green visitors’ seats stayed largely empty.

Adjusting the microphone down closer to her mouth, Spaw introduced herself for the record—though everyone in attendance knew who she was. Just nine months earlier, she had been honored by the chamber in a resolution celebrating her work ethic, her diplomacy, and “her loyalty to each of the members of the Senate.” As she opened a three-ring binder resting before her, Spaw started her testimony with a confident declaration: “It is my opinion as secretary of the Senate that we do not tolerate sexual harassment. If we know about it, we would investigate it,” said Spaw. “It is true that the policy needs to be updated.”

Sams provided an overview of the Senate’s written and unwritten policy, noting that as secretary, Spaw would receive investigative reports resulting from complaints and consult the perpetrator’s supervisor about any resulting discipline. If a senator had been investigated and was found to have committed an offense, Sams said, Spaw would decide what to do based on the “seriousness of the conduct.”

“For something like off-color jokes or remarks, the secretary would address the issue with the senator,” Sams said, adding that Spaw would take anything more serious to the administration committee chair and the lieutenant governor. During the remaining hour, Spaw provided a rare public glimpse into her definition of “serious” misconduct and the policy’s implementation, which, she acknowledged, boiled down to her “interpretation and Delicia[ Sams]’s interpretation.”

When Kolkhorst asked what she’d do after receiving the results of an investigation, Spaw said she followed in her predecessor’s footsteps. “If somebody was uncomfortable or a senator was, you know, making comments that they didn’t like, she just would go to them and talk to them and tell them, ‘You gotta cut it out, knock it off.’ ” She continued: “It’s my belief that anything more than that—that I would need to report it to the chair of administration and to the lieutenant governor and that both would know.”

Sylvia Garcia, a Democrat from Houston—who now serves as a U.S. congresswoman—was the only non–committee member who attended the hearing. She challenged what she saw as Spaw’s notion that senators and administrators could essentially police themselves. When Garcia asked whether the Senate might retain an independent third party to handle investigations, Spaw said that anyone could file a complaint with outside agencies, such as the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or the Civil Rights Division of the Texas Workforce Commission. Though others would conduct investigations, Spaw said, “I will receive the complaint. It will come to me. . . . I will have to respond to it.”

When Senator Royce West, a Democrat from Dallas, asked if the results of an investigation would be subject to open-records requests, Spaw said: “As long as it’s still a draft, it’s not. I would like to make it not subject to it. But, uh—I think it is unless it’s a draft. In other words, it’s not a final report.”

Garcia sought clarity on whether Spaw had received complaints. “The policy was put in place in 1995, and since then, we’ve had absolutely no complaints?” Garcia asked. “Or not since you’ve been here?”

Spaw admitted that she had received “sexual harassment complaints,” adding, “The questions that I’ve been asked by the press have been since 2011 or 2008.”

“Okay, so how many have we had, and how long ago were those?” Garcia prodded.

“Well the only official one that we had,” Spaw said, looking at Sams, “was in 2001.”

“Do you recall how that investigation was handled?” Garcia asked.

Dropping her voice, Spaw said: “Yes, I do.”

Spaw summarized the case as a “staff-to-staff complaint” handled “in-house,” but she omitted the details. Spaw had fired three women in the Senate Media Services department after a Senate employee had complained she was the target “of a virtual cabal” of fellow employees engaged in “lesbian, partisan, anti-Christian harassment, and seduction,” according to a 2001 report published by the Austin Chronicle. The complainant said two women working for the Senate took her to a “restaurant that was predominantly lesbian” and suggested that she change her sexuality. The Chronicle reported that investigators failed to ask the name of the establishment. The third woman, the Senate’s media-services director, wasn’t present but found herself without a job anyway, according to her friend and lawyer, Karl Bayer. “In my heart of hearts I think [she] got fired because she was gay,” Bayer told Texas Monthly, “and the whole thing could have exposed, ‘Oh my god, the Senate has hired gay people.’ ”

In short, according to Spaw’s testimony, the Senate had never received or investigated any sexual harassment complaints against men.

Earlier in the conversation, Spaw contradicted the claim that she knew of only one sexual harassment complaint since 2001. “There are instances where there’s inappropriate conduct in a member’s office and the chief of staff handles it,” she clarified. “We don’t get the complaint.” Five months after that 2017 hearing, the Senate released a new policy, which Spaw and Patrick both praised. The new rules suggest that victims can first ask the offender to stop, if they feel comfortable doing so. Tippett, the employment lawyer, says this guidance could be read as an expectation for a complainant to confront their abuser.

A victim may also contact supervisors and chiefs of staff “for assistance in resolving the issue.” If they don’t feel comfortable reporting to those officials, the policy says, they may submit a complaint directly to human resources or the secretary of the Senate. Then, as before, the policy states, the Senate will initiate an immediate investigation of any complaint, conducted by the director of human resources and by impartial attorneys. Outside attorneys or investigators may be engaged. Results are to be turned over to the secretary, and if the report indicates that sexual harassment has occurred, the Senate or an office supervisor will take the “appropriate action” to resolve the problem. Actions may range from a written reprimand to termination, but the policy doesn’t explain exactly what type of discipline will apply to what cases. (According to Sams’s testimony, under the old policy, if a senator had committed “serious” sexual harassment, the lieutenant governor and the chair of the administration committee would “make a decision on the appropriate remedial action.”)

Both Patrick’s press secretary and Spaw also highlighted a change in the rules requiring the lieutenant governor, senators, and all their staffers to participate in training on what constitutes sexual harassment. “This was a significant improvement to the policy and unanimously agreed to,” Spaw wrote to Texas Monthly.

Under the Texas Penal Code, public servants are specifically prohibited from subjecting anyone to sexual harassment—an abuse of power that can constitute a Class A misdemeanor or, in very rare cases, a felony. Even if an allegation was never directly made to Spaw’s office, Texas law requires employers to take immediate and appropriate action if they “know” or “should have known” that harassment was occurring. But instead of exercising their expansive control and investigative powers, Spaw and Patrick have punted responsibility when complaints arise, providing wide discretion to senators and their offices to handle them, Texas Monthly has found.

There is nothing in the policy explicitly stating whether supervisors need to investigate a complaint or report it to Spaw. If that is a “loophole” Spaw is exploiting by claiming not to have any records of complaints or investigations related to sexual harassment, it’s a weak excuse, said Banks, the employment lawyer. Allowing individual supervisors to avoid the process articulated in the policy is a “terrible way to handle a complaint of sexual harassment—which is to have interested individuals conduct an investigation where there’s no sunlight on it whatsoever,” Banks said. Providing an independent inquiry and transparency “is, like, Sexual Harassment Investigations 101.”

Given the outline of the story in Menéndez’s office and the administration’s response to it, Banks concluded that Lila’s case was buried.

By the time Tomas Larralde was fired, he’d had a decades-long history of making at least seven women, including another intern in Lila’s cohort, uncomfortable in the workplace, Texas Monthly has learned.

Leticia Van de Putte, who served as a state senator for San Antonio from 1999 to 2015, inherited Larralde from her predecessor but decided not to retain him. Van de Putte said she heard about his treatment of female colleagues at least as early as 2019 and noted that it had left a bad taste in her mouth. When asked about his 2021 firing by Menéndez, she said bluntly: “That needed to happen.” That kind of “behavior catches up to you.” Before that happened for Larralde, however, he went on to work in Uresti’s office and later for Menéndez.

Menéndez won a special election to fill Van de Putte’s seat and quickly learned that the fourteen years he’d spent in the Texas House hadn’t prepared him for the internal machinations of the Senate. He described the onboarding process as “Here’s your budget, good luck.” So when he heard about a potential hire who’d previously worked for Van de Putte, the senator-elect brought him on. “I wouldn’t have hired him,” Menéndez said, “if I knew that there was a pattern” of misconduct toward women.

In Larralde’s first year in his new gig, one of Menéndez’s former staffers said she saw him “touching and grabbing people inappropriately,” belittling the women around him, and making vulgar jokes about “cocks” and “breasts.” The staffer says she discussed his behavior repeatedly with Menéndez. “I told him many times,” she said, “ ‘Your chief of staff is talking to people in a certain way, touching people in a certain way.’ ” The staffer resigned after that session, telling Texas Monthly she could no longer work with Larralde, whom she called a “monster.”

Ina Minjarez, then a Democratic representative, got involved in the Larralde situation in 2017. That year, Minjarez and Menéndez, members of the San Antonio delegation, worked together on a piece of legislation. An argument erupted between Larralde and members of Minjarez’s staff, according to screenshots of contemporaneous texts between the two lawmakers as well as interviews with people who witnessed the exchange or heard about it shortly afterward. Minjarez says she was told that Larralde called her a “bitch.”

That same day, she confronted the senator about his chief of staff’s behavior. In the texts, Menéndez apologized on behalf of his office but said his hands were tied because he hadn’t witnessed the exchange. Afterward Minjarez declared that Larralde was no longer allowed to contact anyone on her staff.

“I get a call saying he’s rude. He’s disrespectful. He lost his temper. Okay, ‘I’m sorry,’ ” Menéndez said. “That’s common in politics when you’re having disagreements.” In fact, that’s how Larralde portrayed himself, said the senator: “ ‘I’m the bad guy so you can be the good guy. I get it done.’ ”

It wasn’t until Lila’s case in 2021 that Menéndez took action against Larralde. Asked why he directed Larralde to sign an NDA, the senator emphasized that Cruz told him Lila “didn’t want any attention whatsoever” and didn’t “want anybody talking about this.” Lila’s response to Menéndez’s statements, upon recently hearing them for the first time, was succinct: “I was never asked about how I felt about privacy or what the senator could or couldn’t say to people.”

The public perception that Larralde was fired over the DWI arrest, not sexual harassment, “was an assumption,” Menéndez said, “because of a lack of other facts.”

As to the previous complaints made to him about Larralde, Menéndez said, “If you want to go back to 1997, I challenge anybody to bring anything forward that I’ve done wrong.” He added, “If they’re catching me on my way out of the office, and they say, ‘This happened,’ or something, maybe I didn’t pay enough attention. Maybe I didn’t stop and say, ‘You know, I’ll give you the time to have a meeting.’ ” He later said, “I’m frustrated by people who feel that they told me something that was so serious. They should put it in writing.”

While Minjarez warned Menéndez about Larralde, she sees the case as part of a larger problem. She blames the Senate’s administrative apparatus for “taking an active role in silencing harassment complaints and protecting its members.” The Senate leadership, she says, thinks “it’s best to keep its dirty laundry a secret.”

Others, however, pointed fingers at the senator. “It’s not just Tomas [Larralde] who is responsible,” said a former Menéndez staffer. “It’s José [Menéndez]. He covered it up.” She added that Larralde “just thought this was the culture” of the Senate.

On that score, at least, he may have been right.

Office locations signal power in the state Senate, and proximity to the floor is the currency. An encaustic-tiled hall spans the back of the chamber, leading to meeting rooms decorated with artwork, including a large-scale portrait of Sam Houston wearing a Roman-style toga. At either end of the corridor sit two glass-enclosed offices. The north is Spaw’s domain. The south, with views of the downtown skyline, is Dan Patrick’s.

Though Spaw is beholden to senators, insiders pointed out that in practice, she serves at Patrick’s will—a characterization the lieutenant governor’s spokesman disputed. Republican former senator Kel Seliger, of Amarillo, called Spaw “an absolute state treasure” who is loyal to the Senate as an institution above all else. He said that lawmakers approach her because “she knows the rules and thinks people oughta follow the rules.” The primary rule is simple: those who don’t bend the knee to Patrick, Seliger said, can expect one thing: “retribution.”

Patrick enjoys nearly absolute power over the Senate and its policies. Seliger said if Spaw were aware of any “breach of law or an action that was generally detrimental to the Senate,” she’d “feel compelled” to inform the lieutenant governor about it.

In response to multiple requests for interviews about the role that Patrick plays in policy enforcement and oversight of senators’ conduct, the lieutenant governor’s office sent a brief statement: “In 2018, the Lt. Governor called for the Senate sexual harassment policy to be updated. The new policy is designed to include and protect everyone working in and around the Capitol. It is a robust policy that offers multiple avenues for victims to report sexual harassment without fear of retaliation while providing a fair and just process for those accused.”

Of course, not everyone agrees with the A+ grade that Patrick has awarded himself. In February state senator Sarah Eckhardt, an Austin Democrat, submitted a request asking that the Senate examine the chamber’s “response to workplace harassment claims.” Patrick declined to include it in his priorities for the 2025 legislative session.

Ana Ramón worked as a legislative staffer during five sessions in the Senate and House and now serves as the executive director of Annie’s List, which supports progressive female candidates in Texas. “The sentiment has been about protecting the Senate and the institution and not the victims,” she said. Ramón’s assessment was supported by a half dozen other sources in the Legislature and was shared by young women who reported—or watched a colleague report—harassment to Spaw and her deputies. As a result, sexual harassment is “par for the course” in the Senate, said Ramón.

The other chamber of the Legislature has been more proactive in addressing sexual harassment. In 2018 a work group in the House convened by then-Speaker Joe Straus asked a research team from the University of Texas to administer a questionnaire to employees on their perceptions of the chamber’s sexual harassment policy. Those results were returned within months. Now the House’s General Investigating Committee is responsible for looking into complaints. The committee has subpoena power and the ability to hold an alleged abuser in contempt if they decline to cooperate with an investigation. The House policy also includes provisions to avoid conflicts of interest, stipulating that the committee will appoint an independent investigator if a complaint involves a House member.

This new apparatus was tested in 2023, when then–Republican representative Bryan Slaton, 45, a married former pastor from Royse City, got a 19-year-old woman on his staff drunk and then had sex with her. The committee investigated Slaton, and the House voted to expel him based on its reports. At any time, Patrick could form a similar committee in the Senate, or task its current committees with similar inquiries, but he has not done so, and he won’t say why not.

Though his chamber’s written policy now contains some best practices for addressing sexual harassment, “if they don’t enforce the policy, it’s not that valuable,” said Tippett. “There’s the policy on paper, then the policy in practice.”

Perhaps no case better exemplifies how Patrick approaches reports of sexual harassment than that of Senator Charles Schwertner, a Republican from Georgetown. Serving in the chamber since 2013, the surgeon with thinning brown hair stands at six two. He’s one of Patrick’s most loyal lieutenants and has enjoyed his unwavering support.

Schwertner, who did not respond to requests for an interview or to a list of detailed questions, has for years developed an unseemly reputation among female Senate staffers. When Kara got her job in the Senate, in 2017, she heard him described by others in the chamber as creepy—a doctor, a messenger said, whom you wouldn’t trust with your daughter. The Senate’s whisper network warned young women to steer clear of him. But Kara found that was impossible. “Every corner I turned, he was there,” she told Texas Monthly. “He would flirt with me or tell me I looked nice. I didn’t like it.”

Schwertner’s advances escalated throughout the session, Kara said. While he was leaving a committee hearing one day in May, Schwertner approached her alone in a break room. She says he encouraged her to seek him out to discuss her career and then passed her a piece of paper. On it was his contact information for an encrypted messenger app called Dust that boasts high-level security and permanent deletion of texts, and once used a provocative tagline: “The app that protects your ass(ets).”

Kara had never heard of it. Soon after, she said, the senator hounded her and kept asking why she hadn’t reached out, even questioning whether she was lacking in ambition. “I felt very much like the prey that was outrunning him,” she said, “and that made him be more aggressive.”

Later that same month, Schwertner once again approached Kara in a break room, she said, and started lamenting that he was going to miss seeing her when the session ended. Then he pulled her in for a hug and grabbed her butt. Kara said she spent the rest of the day feeling untethered. When she got home, she threw up. She took off her pantyhose and skirt, shoved them in the trash, and scrubbed her skin in the shower. But by the time Schwertner groped her, Kara had already been yelled at and demeaned after reporting Uresti, and she was convinced that it would be a mistake to inform her superiors. “I knew if I told Rick [DeLeon] what had happened,” she said, “I would be fired because I was asking for it.”

After Kara moved on from her time in the Senate, another young woman complained about Schwertner. In the spring of 2018, the woman, a studious 25-year-old member of a statewide health association, attended a professional event that was promoted by the University of Texas. During a brief interaction with Schwertner at the event, Maya (whose name has been changed to protect her from retaliation) expressed an interest in pursuing a career in health advocacy. A few days later, Schwertner, the chairman of the Health and Human Services Committee, messaged her on LinkedIn. “Nice meeting you!” the senator wrote. “Please reach out if you ever need anything.”

They began a brief exchange as Maya asked about the senator’s journey from medicine to politics. She realized they were planning to attend the same health-care conference that summer. There, Maya was surprised when the senator remembered her name. He handed her his card with a handwritten phone number. “I thought that was super sketchy,” she told Texas Monthly. “I did not call.”

A few weeks later, she received a voicemail from Schwertner’s chief of staff, who’d gotten her phone number from the CEO of the professional association that ran the conference. In the message, played for Texas Monthly, the chief of staff said he’d heard Maya was interested in working at the Capitol and invited her to attend a hearing. Thinking it was an opportunity for professional advancement, Maya made arrangements with the chief of staff and committee staff.

Then, on August 28, 2018, a few days before the hearing, Maya received a message from Schwertner on LinkedIn asking for her cellphone number. He added later that he wouldn’t be able to make the hearing invitation work. She replied with her number and said she understood. An hour and a half later, she got a text that appeared to be from him: “Sorry. I really just wanted to f[—] you.” Then: “This is Charles.” Then: “Send a pic?”

“It’s me,” he continued when she didn’t respond. “Want me to prove?”

Minutes later he texted, “And I have more proof of life,” with a winking emoticon, accompanied by a photo of a penis.

“Please stop, this is unprofessional,” Maya finally replied. “I’m a student interested in learning about healthcare policy. These advances are unwanted.”

Maya recounted the incident to a dean at UT, who was required to report any such complaints under provisions of Title IX of the federal Education Amendments of 1972. “I am also afraid he will do this to another woman,” she told officials at the time. UT opened an investigation and hired Johnny Sutton, a former U.S. attorney for the Western District of Texas, to conduct it. When the story first made headlines, Patrick issued a statement: “The Texas Senate is awaiting the conclusion of the investigation and expects a full report on this matter.”

Sutton and his team found that the handwritten number on the business card Schwertner gave Maya was purchased through Hushed, a “second number app” that keeps your “real phone number” hidden, according to its website. Schwertner claimed, through his attorneys, that the messages were from someone else. His lawyers told investigators that the senator had shared his usernames and passwords with a third party. A forensic analysis found that the photo had been sent from a device that wasn’t Schwertner’s phone. Sutton noted that it was plausible that a third party had sent it, or that Schwertner sent it from a different device, such as an iPad. Schwertner refused to meet with Sutton, to be interviewed, or to answer five written questions, and he declined to name the third party he blamed.

The final investigative report concluded that Maya had received uninvited and offensive texts that she reasonably believed came from Schwertner, but Sutton did not have the power to legally compel Schwertner to testify or hand over evidence that would have settled the matter—power that Dan Patrick’s Senate chose not to wield. Schwertner and his attorneys publicly proclaimed that the senator had been “cleared” and that the report confirmed his “innocence.” But the report provided no determination as to whether he’d violated either university policy or federal law, citing the senator’s refusal to cooperate and a lack of available evidence. No Senate committees, which have the subpoena power UT does not, subsequently pursued the matter. When asked why Patrick chose not to investigate further, a spokesperson for the lieutenant governor said the matter was “handled by the university and no complaint was filed with the Office of the Lt. Governor or the Texas Senate.”

Schwertner voluntarily removed himself as chairman of Health and Human Services in 2019. A session later, Patrick named him the head of the Senate Committee on Administration—the same committee that handles personnel issues and is supposed to enforce the chamber’s sexual harassment policies. The move signaled to many that he was “back in the fold,” as Texas Monthly reported in a story at the time. The message many heard was that Patrick wasn’t serious about sexual harassment complaints and that as long as a lawmaker did as he commanded in the Senate, Patrick would have his back.

In February 2023 Austin police officers arrested Schwertner and charged him with driving while intoxicated. A few weeks later Patrick gave the senator a bear hug during a press conference at the Capitol about the Texas electric grid and repeatedly emphasized how “proud” he was of his protégé. (Travis County attorney Delia Garza said in July that her office would not pursue the charges because there was not sufficient evidence to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.) Since then, Schwertner’s appointments from Patrick have gotten more prestigious: last session he chaired the Business and Commerce Committee as well as the Sunset Advisory Commission, which evaluates the performance of state agencies.

That lack of accountability still stings for Maya. In the moment, the lewd messages struck her as more absurd than damaging. But going through the Title IX process was traumatizing: having the investigation leaked to the media, worrying that she’d be exposed and blackballed in her career, and seeing the senator avoid any legal or political consequences. “It was just frustrating because all these people are saying he’s such a good guy, he’s a family man,” Maya said. “There’s data evidence and there’s time stamps and there’s IP addresses” on the messages. “How is this still happening?”

Senate leadership’s tolerance of members who are accused of sexual misconduct isn’t limited to partisan favorites. Exhibit A, according to sources in the upper chamber, is Senator Borris Miles, of Houston. In 2008 Miles was indicted on two counts of deadly conduct, including pulling out a gun at a party where he was alleged to have forcibly kissed a woman. A jury acquitted Miles of the criminal charges, but the woman sued for assault and battery, resulting in a settlement. “That’s what Borris does,” one lobbyist said. “He does it for shock value. Whether he kisses your wife or puts a pistol in your hand, he wants you to understand that he’s capable of just about everything.”

Miles did not respond to multiple requests for an interview or to specific questions about allegations against him. His spokesperson has denied previous allegations, calling them “unfounded and implausible.”

Five women told Texas Monthly that Miles harassed them: Two said that he forcibly kissed them, one that he groped her, one that he propositioned her. Another said he cornered her, suggested she had been hitting on him, and ogled her in a “cartoonishly obvious” way. None of the women reported Miles’s behavior to Spaw, but several allegations against him were prominently featured in multiple stories for the Daily Beast in 2017. Patrick could have ordered an investigation but chose not to—again, a spokesperson said, because “the Lt. Governor’s office has not received a complaint.” And Miles didn’t stop. One woman told Texas Monthly that Miles forcibly kissed her in a nighttime meeting in the Capitol in 2019.

In the past, Miles has given little credence to anonymous accusations, and his career has been relatively unaffected by them. Now, for the first time, an accuser is willing to come forward by name: 36-year-old Tayhlor Coleman, a Houston native who works as a political consultant and voting-rights activist. She shares a church community and even a sickle cell anemia diagnosis with Miles. “Especially as a Black woman anchored in the Third Ward, to work in politics, you’ve got to go through Borris,” she said. “There is no escaping him.”

Like the other women who spoke to Texas Monthly, Coleman said she was warned about Miles well before she attended a party thrown by U.S. representative Joaquin Castro in San Antonio in June 2016. Coleman, who was then 27, greeted Miles when she saw him. “I try to make it a point to shake people’s hands,” Coleman said. “But he specifically grabbed me in for a hug, slid his hand down, and palmed my butt.”

Coleman said recently, “I just remember freezing in that moment. I’m working, so it’s not like I could turn around and punch the guy in the face.” Paralyzed, she said nothing. Miles, she said, told her she should come “party” with him that night.

A spokeswoman for Castro said the congressman did not witness the incident and was unaware of the allegation against Miles until speaking to Texas Monthly but “condemns any kind of harassment or mistreatment.” Castro also condemned the state’s leadership for not acting more aggressively to curb sexual harassment. In an interview, he blamed “a culture of corruption” that has persisted for decades. “Say what you will about Congress,” Castro added, “and there’s plenty of unflattering things to say, but there’s a fairly strict ethics system. And there has, in my experience, been much better enforcement in Congress than in the state Legislature.”

That Miles felt “entitled to grab my ass in front of all of these people” was creepy but unsurprising, said Coleman. Still, the prospect of reporting it—to a boss, to anyone—seemed daunting. “Everybody knew that this is who this man was, and there had never been accountability. I didn’t see any value in opening myself up to retaliation.”

Nearly a decade later, she feels differently. “I’m just not f—ing scared of these guys anymore,” Coleman said recently. “It’s not that I don’t think there might be consequences,” but where there was fear and shame, she said, something else has grown in its place: “rage.”

Coleman—and the other women interviewed for this story—believe that their speaking out about powerful abusers is necessary for progress on the issue, but they want support. They say the senators’ peers need to step up. “The folks who claim to care about the rights of women, that we’re treated equally and that we have freedom over our own bodies: that goes for your colleagues groping us,” Coleman said. “Unless you are willing to hold these people accountable—that makes you complicit.”

When interviewed for this story, several lawmakers voiced broad support for zero tolerance of harassment, including state senators Joan Huffman, a Republican, and Carol Alvarado, a Democrat, both from Houston. Senator Judith Zaffirini, a Laredo Democrat, warned her colleagues, in 2018, against hollow rhetoric about sexual abuse. Now, as dean of the Senate—the member who has served longest—Zaffirini is renewing her appeal to “take all accusations of sexual misconduct seriously and provide support to victims.”

In the meantime, accusers say, the Texas Senate loses female talent. That’s why sexual harassment is a form of employment discrimination under federal law, said Tippett, “because you can’t do your job very well if you’re being harassed, or your workplace is intolerable and you leave—either way it prevents your access to opportunities.”

Several of the women who spoke to Texas Monthly said they moved or changed careers after their experiences. Coleman moved to Washington, D.C., for a while. “There is such a dearth of talented women because of the harassment that they face,” she said of Texas politics. Grace Gnasigamany left her job interview with DeLeon seething over how questions about what she wore overshadowed any interest in her qualifications. But like many of the women interviewed for this story, she took the job anyway and kept her head down. “I just did it for the summer and never thought about it again,” she said. At the end of her internship, instead of pursuing politics, she moved to Los Angeles and went into entertainment law.

Maya, too, gave up on the idea of bridging her passion for health care with Texas politics. That she never worked in the Capitol gave her the confidence to report what happened in the first place. “I had no skin in the game. When I said no [to Schwertner], I was like, ‘I don’t have a career in politics, and I’m definitely not going to after that,’ ” she said. “I’m in a different profession, so if no one else is going to say something, I’m going to.”

Several of the women who suffered harassment say it took a serious toll on their mental health. Kara still works in Texas politics but said she’s in therapy and, even eight years later, gets nervous around men—and doesn’t like to be alone with any at work. Nearly seven years after she met Schwertner, Maya teared up when recounting her experience. The anxiety that the public will learn that she was at the center of such a high-profile accusation remains strong.

For Lila, things got worse after Larralde’s 2021 exit. She sought therapy and vented in her journal about her worsening anxiety, weight loss, and frequent crying. “I don’t know how to cope or deal with it,” she wrote. “I don’t feel supported or heard.”

At the end of her internship, Lila tried to tell Senator Menéndez how much she’d struggled. She approached him in his fluorescent-lit district office in a mall where elderly San Antonio residents saunter in the halls for exercise. The senator, who says he cannot recall this meeting, had his head down, signing documents. “I was telling him how working in his office had given me really bad depression, and my therapist wanted to put me on antidepressants,” she said. “I was choking on my words. I was ready to cry.”

Menéndez advised her not to get on antidepressants and wished her well, she said, adding that he hoped some time off would help. Then, she recalled, he asked her to leave his office.

Olivia Messer is a journalist who has covered sexual harassment in the Texas Capitol for more than ten years. Cara Kelly is an investigative editor and adjunct professor at American University’s School of Communication.

This article appears in the August 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Dome of Silence: Sexual Harassment in the Texas Senate.” Subscribe today.