Ever since China ended its “zero-Covid” policy late last month, its hospitals have been overwhelmed by cases. But as concerns grow about the threat of new variants Beijing has been criticised by global health bodies for a lack of transparency about the prevalence of the virus in the country.

At least 15 countries have introduced mandatory Covid testing for travellers arriving from China, mostly to ensure that no dangerous variants go undetected. The UK Health Security Agency, for example, has asked hospitals to sequence all viral samples from patients who have arrived from China that are hospitalised with Covid.

But are surging infection rates likely to lead to powerful variants from China or other countries with current high caseloads, such as the US? The chances are seen as low by many epidemiologists though they remain concerned that a lack of transparency in some countries could hinder detection.

What do we know about variants in China?

Gisaid, the global repository of genomes that allows scientists to track coronavirus as it mutates, on Tuesday said the samples uploaded to its database “all closely resemble known globally circulating variants seen in different parts of the world between July and December”.

Data presented to the World Health Organization, an analysis of which was published on Wednesday, reached a similar conclusion. “No new variant or mutation of known significance is noted in the publicly available sequence data,” the health body said.

Peter Bogner, Gisaid’s chief executive, said it was “a grave mistake” to focus solely on acquiring timely data from China, because “new variants of significance can appear anywhere in the world”.

“Unfortunately we’re starting to see surveillance gaps appear across the globe,” he told the Financial Times.

“[But] China is actively ramping up its efforts in making available more data on circulating variants, so our surveillance lens in Asia is getting sharper by the day. It would thus be advisable to trust science over politics.”

Why do passengers from China face restrictions?

Western health officials say privately that the checks on travellers have mostly been introduced to avert potential variants spreading undetected but that the current measures are not justified by any existing threat. One senior European official, who declined to be named, said it was a “political” decision, citing “governments that want to be seen as protecting their own people”.

China was criticised earlier in the pandemic for its reticence on publishing Covid data, which may have made western officials wary of Beijing’s approach, according to officials familiar with the thinking in European capitals. Beijing’s strict zero-Covid policy for most of the past three years in turn makes restrictions on arrivals from China more politically palatable, they add.

The current “intense” rates of transmission made it “understandable” that countries were taking steps to protect their citizens, WHO said on Wednesday. Moreover, the 13mn cases reported to WHO in the past month were considered to be an “underestimate”, said the Geneva-based health body.

Mike Ryan, head of WHO’s emergencies programme, said some countries had opted for caution as a hedge against new variants amid a relative lack of data, adding it “would be much better if we had much more extensive sequencing”.

Where do new variants come from?

Viruses inevitably undergo genetic mutations as they reproduce within their hosts. A few variants prosper because they spread more readily between people than existing strains, by overcoming their immune defences and binding themselves more efficiently to human cells.

There are competing theories about exactly where new variants originate, because it is impossible to identify the true patient zero, the first carrier of the virus.

The most popular view among virologists is that most significant variants result from chronic infection in an immunosuppressed person who cannot clear the virus for several months, giving a series of mutations time to develop.

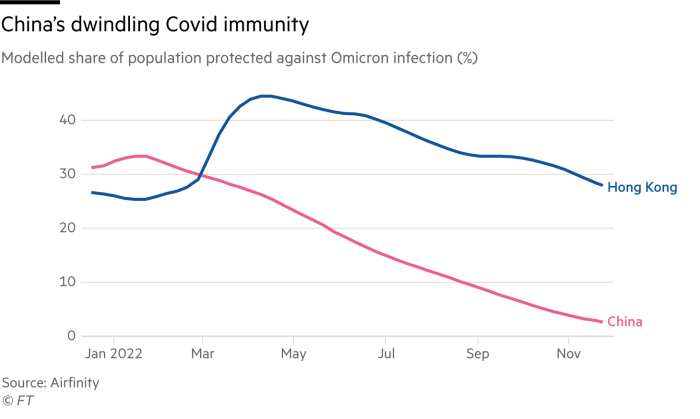

Which variants thrive will depend on a population’s immunity levels as determined by rates of previous infection or vaccination. Strains of Omicron, the dominant variant in many countries since late 2021, which are now surging through China may not be best adapted to transmit through European or American populations with different immune profiles.

Which variants are spreading beyond China?

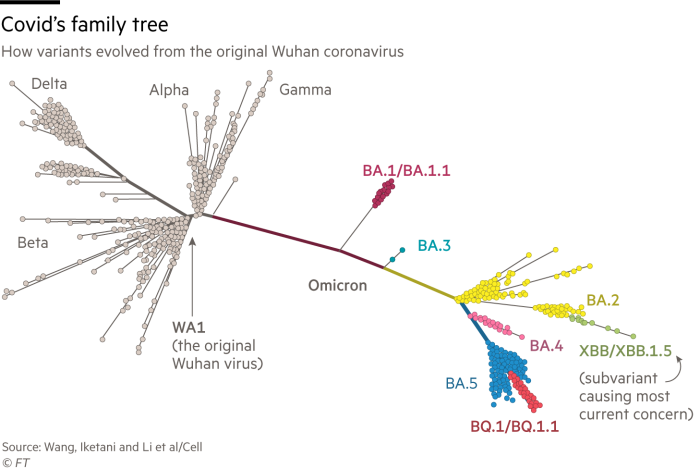

Omicron’s descendants dominate transmission worldwide. The original Sars-Cov-2 virus and Omicron’s predecessor variants, officially denoted by Greek letters, are almost extinct. The Omega subvariant causing most concern among virologists is XBB.1.5, which seems to have originated in the north-eastern US in October and is spreading rapidly across the country.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, XBB.1.5 was responsible for 40 per cent of US cases during the last week of December. XBB.1.5 is on the increase in Europe and has been identified in more than 25 countries, the WHO said on Wednesday.

XBB.1.5 is informally called Kraken after the mythological sea monster, one of a number nicknames that scientists have applied “to help people keep track of the ever-growing variant soup”, said Ryan Gregory, an evolutionary biologist at Canada’s University of Guelph in Canada. “There are now more than 650 Omicron subvariants.”

Kraken is descended from XBB or Gryphon — itself a hybrid of two Omicron BA.2 descendants. A key mutation enables XBB.1.5 to transmit rapidly between people by evading antibodies conferred by previous infection or vaccination, while at the same time binding more tightly to human cells.

“While there’s still much to learn about this variant, it doesn’t have the look of a ‘scariant’,” said Eric Topol, professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research in California, referring to the term he coined for strains that sound scary but are not really dangerous. “This one is the real deal and we’re betting on our immunity wall of infections, vaccinations, boosters and their combinations to help withstand its impact,” he added.