[ad_1]

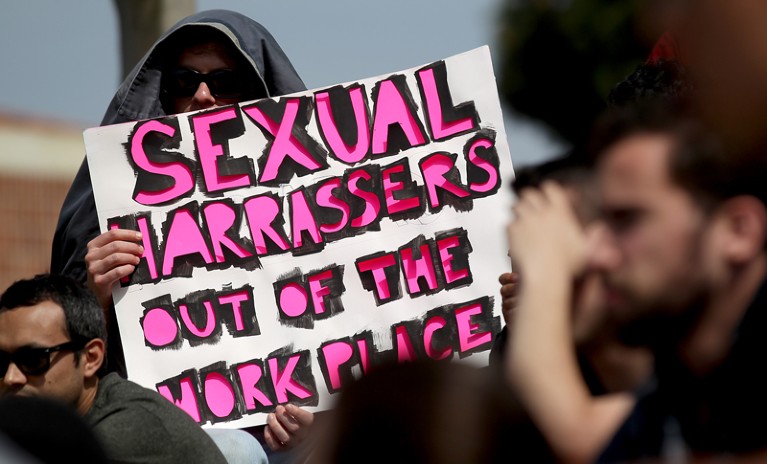

Students at a California university protest over the handling of a sexual-harassment case.Credit: Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times/Getty

In 2015, an assistant dean at a University of Wisconsin campus resigned following allegations that he had sexually harassed a campus employee. During the next two years, he took similar jobs at two other universities, neither of which learnt of the investigation or its findings during reference checks. He eventually resigned from the second position, which was at another of the 26 campuses of the University of Wisconsin system, after former colleagues contacted the institution about the original harassment investigation.

The case and others like it have provoked media coverage when they are exposed and, at the University of Wisconsin, have led to a revamping of policies to prevent similar scenarios from playing out. But for each high-profile example in which an accused harasser ends up, and sometimes reoffends, at another institution, there are many others that don’t receive public attention and so go uncounted, says Susan Fortney, a law scholar at Texas A&M University in Fort Worth who specializes in legal and organizational ethics.

The #MeToo movement, which encourages people to share experiences of sexual abuse and harassment, has increasingly led to such ‘pass-the-harasser’ cases coming to light — so named because individuals are able to move to another employer without them knowing about past misconduct findings. This has led to some high-profile court cases and disputes. For example, in August last year, prominent biologist David Sabatini resigned from his position at the Whitehead Institute, a non-profit institution in Cambridge associated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, after an investigation by a law firm disclosed that he had sexually harassed a Whitehead employee. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which provided funding for Sabatini’s laboratory at Whitehead, ended his contract because of the investigation’s results.

When it emerged this May that Sabatini was being considered for a position at New York University, students and faculty members there protested. Sabatini withdrew from consideration, saying he did not want to distract from the university’s work. He denies the allegations and has filed defamation lawsuits against the Whitehead Institute and two individuals involved in the case. In a response to Nature, Sabatini denies being a harasser, adding: “I had no opportunity to respond to [the investigation] before the decision to fire me was made. I resigned rather than be fired. The way my reputation was destroyed makes a mockery of due process.”

Sexual harassment is rife in the sciences, finds landmark US study

In response to such high-profile cases, some US institutions are developing procedures aimed at identifying people with a history of sexual harassment during the hiring process. They include the University of Wisconsin system and the University of California, Davis, which both implemented new policies in 2019. Among other measures, these require asking candidates more questions about previous misconduct investigations. And in 2020, the state of Washington passed a law to address pass-the-harasser cases by requiring that applicants declare any sexual-misconduct investigations or findings, and mandating that public institutions in the state request histories of sexual-harassment offences from previous employers.

They are not alone. The US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) in Washington DC is also highlighting the issue through working groups and public forums, including a panel Fortney spoke on last October at an annual summit organized by the academies’ Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education. Most of the 28 founding members of the collaborative are US universities, colleges and research institutions. Although pass-the-harasser is by no means limited to the United States, the summit highlighted a handful of US-based efforts to address it. “The next question is, how do you get universities on board nationwide?” Fortney says. “This is truly a national problem. And it requires a national solution.”

A festering problem

Harassment in higher education has been a problem for decades, reports show. In a 2003 review1, nearly 60% of female employees in academia reported experiencing potentially harassing behaviours. A 2020 study found that almost 42% of undergraduates, graduates and professionals at universities had experienced at least one type of sexually harassing behaviour2. This ranged from non-consensual sexual contact to stalking and rape. Among that proportion, 5.5% of undergraduate women and 24% of graduate and professional women reported being harassed by a faculty member2. And a 2018 review3 of more than 300 sexual-harassment cases found that 53% involve serial offenders. Although harassment can occur between any combination of genders and gender identities, the overwhelming number of cases in academia are of men harassing cisgender female, transgender, non-binary, genderqueer or gender-questioning colleagues and students.

Workplace harassment can harm a scientist’s life and career prospects — leading to depression, anxiety, sleep disruptions, trouble concentrating, avoidance of the harasser and other outcomes that can impair academic performance. Success in academia depends on hierarchies of mentors and advisers, who can have a strong influence on career advancement and financial stability for early-career researchers, says Frazier Benya, director of NASEM’s Action Collaborative. This steep power differential opens the door for harassers to abuse it and for harassment to go unreported, she says.

Julia, a geologist and tenured professor in the United States who has published influential studies in high-impact journals, has been bullied repeatedly by a prestigious scientist and former collaborator from another institution who confessed to having romantic feelings for her. After she refused to share accommodation with him during a conference, she says, his stalking and vindictive behaviour worsened. The geologist, who asked Nature to refer to her by a pseudonym to guard against career repercussions and prevent future harassment by the same person, says that her former collaborator has criticized her in online forums.

Harassment can be even more devastating for early-career scientists, says Julia, who avoids conferences and other places where she might encounter her harasser. His behaviour harms her research and productivity, she adds. “This person is so powerful and has such a broad reach that it’s impossible for me not to cross paths with him,” she says. “Now, I’m having to exclude myself from work that I love and is important, because it’s [become] a toxic space for me.”

Fortney and her colleague Theresa Morris have written4 about how the problem continues to escalate, in part because harassers manage to switch institutions without disclosing past accusations. Hiring institutions don’t ask. Previous employers don’t bother to share.

Women gather with placards in support of victims speaking at the trial of a university sexual harasser in the US Midwest.Credit: Anthony Lanzilote/Getty

Quinn Williams, general counsel at the University of Wisconsin system, who is based in Madison, says that a major reason disclosure doesn’t happen, historically and today, is employers’ fear of potential defamation claims by people whose employment contracts are terminated for reasons they deny. Academic employers might find it easier to let harassers leave, resign or settle a claim with the hope of limiting public scrutiny, reputational damage and ongoing risk. But, he says, that is short-sighted because not disclosing harassment findings can backfire on institutions, potentially bringing more legal, reputational and financial harm.

Also, Fortney adds, US universities can be sprawling, decentralized networks, in which faculty members are often selected by departments that might not have an official system for checking references. Human-resources offices tend to have limited roles in hiring decisions, she says. Tenure structures make it simpler to let a harasser leave on their own than be fired.

Despite those obstacles, it is essential to work on fixing systemic problems, both for individuals and for science in general, Fortney says. “Students and employees should not be left to study and work in unsafe environments because schools fail to ask and answer questions related to substantiated findings of sexual misconduct,” she says. Tolerance of harassment also amplifies the numbers of women and scientists from under-represented groups who flee the academic workforce, she notes.

A patchwork of state and federal laws makes the situation even murkier for institutions, scientific societies and professional associations, adds Travis York, director of Inclusive STEMM Ecosystems for Equity & Diversity at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Washington DC. “It can be really difficult for organizations to navigate what they can do” if they want to alert a potential future employer to harassment findings, he says.

One by one

Attempts to tackle the pass-the-harasser issue accelerated in 2018 after NASEM published a landmark study5 on sexual harassment, York says.

The serial-offender case at the University of Wisconsin in 2015 was far from the only sign that the institution needed to pay more attention to harassment. According to an investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel newspaper in 2018, more than half of students in the Wisconsin system who responded to a survey in 2015 said they had been sexually harassed. Among female graduate students who reported being harassed in the survey, more than 22% said that their harasser was a faculty member. The newspaper documented nearly 100 formal investigations of sexual misconduct by the university’s employees from 2014 to 2017.

Smithsonian island outpost reeling from sexual-misconduct claims

Williams says the university’s Board of Regents — an appointed governing body that oversees the university system — quickly revised its hiring process. By January 2019, Williams says, its departments started asking applicants about any history of sexual harassment or other misconduct, and sharing records when other institutions asked about former staff.

All job postings, which already disclosed that there would be a criminal-background check, now tell applicants that they will be asked about sexual misconduct. Job candidates must also sign a document allowing past employers and references to release information about previous findings of sexual misconduct. Those don’t automatically disqualify applicants, Williams says, but they trigger a closer look. If an applicant doesn’t disclose, and it is subsequently discovered that they lied or misrepresented their past, it could lead to termination of their contract.

“The absolute minimum requirement,” Williams says, “is that prior to hire, final candidates are asked whether or not they violated any sexual-harassment or sexual-misconduct policies at any previous places of employment, or left during an active investigation into a violation of those policies.”

The University of California, Davis, developed a similar policy around the same time, requiring, among other things, that candidates in the final rounds of consideration give departments permission to ask all previous post-secondary educational employers about findings of misconduct from any formal investigation. (The policy does not cover non-academic employers, which critics say is a key gap.)

Other institutions are starting to follow suit. In May, the US National Institutes of Health announced that institutions receiving grants should report if a principal investigator or someone in a similar position on the grant-award team is disciplined for harassment, bullying or related behaviours. The Ohio State University in Columbus and the University of Illinois system have implemented hiring-disclosure policies, and other institutions have expressed interest in launching their own, says Benya.

Broader policies

In 2019, local media in Seattle covered an investigation into a former University of Washington (UW) sports administrator who was accused of sexual assault by a student athlete. The administrator was subsequently hired by a university in Arizona. Washington’s state governor called for action and Gerry Pollet, a state legislator and UW health-policy lecturer, responded by meeting with survivors, advocates, university officers who oversee compliance with gender-discrimination laws, students and others.

Sexual harassment must not be kept under wraps

Pollet and several other state lawmakers introduced legislation and, in March 2020, Washington became the first US state to approve a law aimed at ending the pass-the-harasser problem. It requires job applicants to sign a statement that discloses any sexual-misconduct investigations or findings, and gives permission to former university employers in Washington to disclose related information. When hiring, public institutions in the state must request information about substantiated findings of misconduct from an applicant’s employers. If they don’t, they will be violating the law. The law also voids any non-disclosure agreements the employee signed with previous employers that might have prevented them from mentioning sexual-harassment findings.

It has taken a while to iron out kinks and misunderstandings in implementation, Pollet says, including delays in the hiring process as a result of contacting other universities and filing requests. He knows of other states considering a law similar to Washington’s, and he wants to work towards inter-state agreements. “Someone has to start the ball rolling, and it’s just like a chain reaction,” he says. “One ball hits another state and it knocks into another state.”

Bumpy road ahead

To motivate more universities nationwide to ask for and provide information, Fortney has proposed an accreditation-based approach. In the United States, this would rely on evaluation by one of at least seven private, regional accreditation agencies, such as the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. These agencies determine whether an institution meets high-quality standards of teaching, student support and other categories. Fortney argues that accreditation should also have a standard for due diligence in hiring that includes disclosure of misconduct investigations. Universities could have leeway in deciding how to meet the standard, but their need to comply would decrease the likelihood that harassers get passed on to other institutions.

An accreditation standard would apply to both public and private non-state institutions, aiding cooperation between them and adding transparency to the hiring processes, Fortney told the 2021 summit. It “communicates that safety really goes beyond bricks and mortar”, she said.

Indecent advances

The Societies Consortium on Sexual Harassment in STEMM, a working group that represents more than 120 academic and professional societies, proposes a flag-sharing system that would highlight individuals who have a record of misconduct. Institutions, organizations and societies could turn to the system when they wanted to give an award or hire or promote someone to a leadership role. If a person were flagged, the system would enable organizations to share relevant information in a legally compliant way. The system itself wouldn’t contain any details.

There would be no obligation to enter the system, but York, an AAAS representative on the consortium task force, thinks people and organizations would be motivated to do so to foster a safer, fairer and more inclusive community. Organizations could also require applicants to be in the system, which would drive participation. The consortium expects to have a pilot programme in place by next year. “We’re moving quickly, but with deliberate intent because we think that this is so important,” says York.

In its report, NASEM found that one of the strongest factors influencing rates of sexual harassment is an organizational climate that conveys tolerance for it, Benya says. Regardless of policies and codes of conduct, harassment will keep happening if people see that there are no consequences. Interrupting that cycle is a main goal of the Action Collaborative’s activities.

These efforts represent a step forwards, says Julia, the geologist, but she suspects these policy changes will catch only a subset of cases, namely those in which harassers are officially investigated. In reality, she says, power structures in academia that depend on peer review, reference letters and collaboration prevent many people from reporting harassment in the first place. When her harasser accepted a high-powered post at a different institution, she felt powerless to do anything about it.

Even if strategies to prevent the pass-the-harasser problem only catch a fraction of bad actors, putting a policy in place “is better than not having this in place, for sure”, she says. “But I think the scope of the problem is so much larger.”

[ad_2]

Source link