Pinti, J., Jónasdóttir, S. H., Record, N. R., & Visser, A. W. (2023). The global contribution of seasonally migrating copepods to the biological carbon pump. Limnology and Oceanography. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.12335

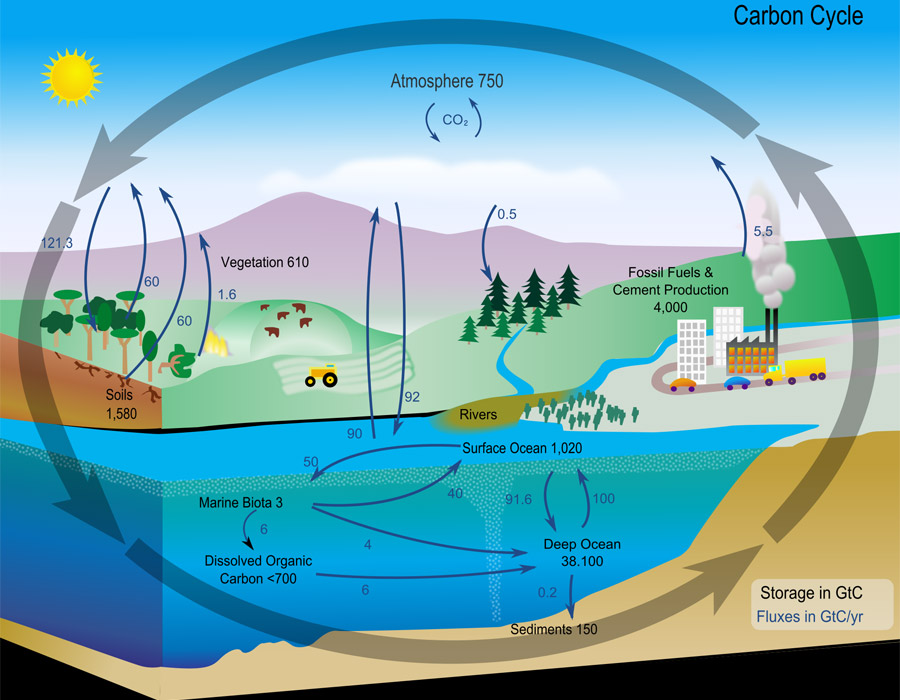

Burning fossil fuels causes the planet to warm up because it puts carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which traps heat. However, carbon in the atmosphere doesn’t just stay put! Some of it physically mixes with the ocean, becoming dissolved in seawater. Other carbon is taken up by living things. Organisms’ bodies are made up of carbon, and they release carbon back into the environment every time they breathe—and poop. Importantly, some of the carbon that ends up in the ocean can be effectively removed from the atmosphere by sinking into deep waters.

When carbon is transported from the surface to depths greater than about 1000 meters, it can take hundreds of years to come back up the surface. By removing carbon from the atmosphere, this process reduces the effects of climate change. Carbon can enter the deep ocean in one of two ways: it can sink (in the form of organic matter, such as fecal pellets or dead animals), or it can be transported by the movement of living organisms themselves. Together, these processes transport many tons of carbon into the deep ocean each year—the so-called “biological carbon pump.”

The largest migrations on earth are in the ocean

One particular group of zooplankton—small crustaceans called copepods—are responsible for massive annual migrations into the deep ocean. These animals become dormant at certain times of year—much like hibernating bears—and basically hide out in deep, dark waters until it’s safe to return to the surface. When these animals migrate to depth, they breathe and poop. Additionally, many of the copepods will die in deep waters due to predation, starvation, or disease, adding their entire body to the pool of deep carbon. Copepods are so numerous (some say they are the most abundant group of animals on Earth) that their annual migration could conceivably transport millions of tons of carbon each year! However, this process is difficult to study, and scientists are still trying to figure out just how much carbon these animals might be moving.

Recently, scientists estimated the amount of carbon transported into the deep ocean by five major species of migrating copepods. To do this, the researchers used data on the abundance of these species at different locations and applied a mathematical model of metabolism. They also used models of deep ocean currents to estimate how much of this carbon is likely to stay at depth long-term.

Little animals have a big effect on our climate

These five species alone were estimated to transport roughly 0.05 petagrams of carbon per year. To put that in perspective, one petagram is about 1 billion tons… so we are talking about some pretty big numbers here. And, because dormancy takes place in deep waters, this carbon is pretty likely to STAY at depth, which is good if we want to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Although these are big numbers, these species still only account for about 1% of the global biological carbon pump—which itself is only about 1% of the total carbon in the atmosphere. Unfortunately, the ocean won’t save us from climate change—we still need to urgently move to a zero-emissions society in order to limit global warming. Nonetheless, these processes are really important. If the biological pump didn’t exist, climate change would be much, much worse. Modeling individual species is difficult because you need a lot of data, but future studies that extend this approach to more species will help fill in the global picture.

An interconnected carbon biosphere

The good news is, by understanding the connections between the ocean and the atmosphere, we can better predict what the climate will look like in the future, and plan our strategies to create the best possible outcomes. We need more basic oceanography to understand where and when zooplankton, such as copepods, live in order to develop better models of the biological pump.

Studies like this also highlight the links between living things and our planet. Not only do migrating zooplankton reduce the amount of carbon in our atmosphere, but the changing climate will in turn impact zooplankton populations in the future. Living things, including humans, are not separate from the atmosphere, the ocean, or the climate. Instead, all of these things are intimately connected and make up the Earth’s biosphere. We influence the climate, and the climate influences us.

I am a PhD student at MIT and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, where I study the evolution and physiology of marine invertebrates. I usually work with zooplankton and sea anemones, and I am especially interested in circadian rhythms of these animals. Outside work, I love to play trumpet, listen to music, and watch hockey.