“For me as a Louisianan, it is not always as severe as, you know, we get a killer storm every three years,” Sanders says. “It’s also as subtle as everyone in this neighborhood walks around in closed-toed shoes because they’re so used to having [flood]water … Sometimes when we’re thinking about research or community engagement projects, we have these big ideas, but a lot of times, it’s right in our face.”

The argument that disasters happen “by design,” when the natural world and the world shaped by humans intersect, was laid out by the sociologist Dennis Mileti in his 1999 book Disasters by Design: A Reassessment of Natural Hazards in the United States. It’s an idea that is widely accepted by disaster researchers—there’s even an international organization called No Natural Disasters. At its conference last year, Sanders was a presenter, explaining how use of the word “natural” removes responsibility from those in power who have the ability to craft policies that could better support vulnerable communities. She pointed as an example to the intersection of industry pollution, sea-level rise, and inadequate infrastructure in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” which is one of the areas the Undivide Project has mapped to demonstrate how these risks compound at residents’ expense.

Sanders hatched the idea for the Undivide Project during the covid-19 pandemic. She was volunteering with RowdyOrb.it, a Baltimore-based organization that trains and hires people to install mesh networks in their own neighborhoods in order to build community, improve access to high-speed internet, and generate local wealth. Walking around one of those neighborhoods in 2019, Sanders remembers, she saw a telltale sign of flooding: water marks on the third or fourth steps leading up to houses.

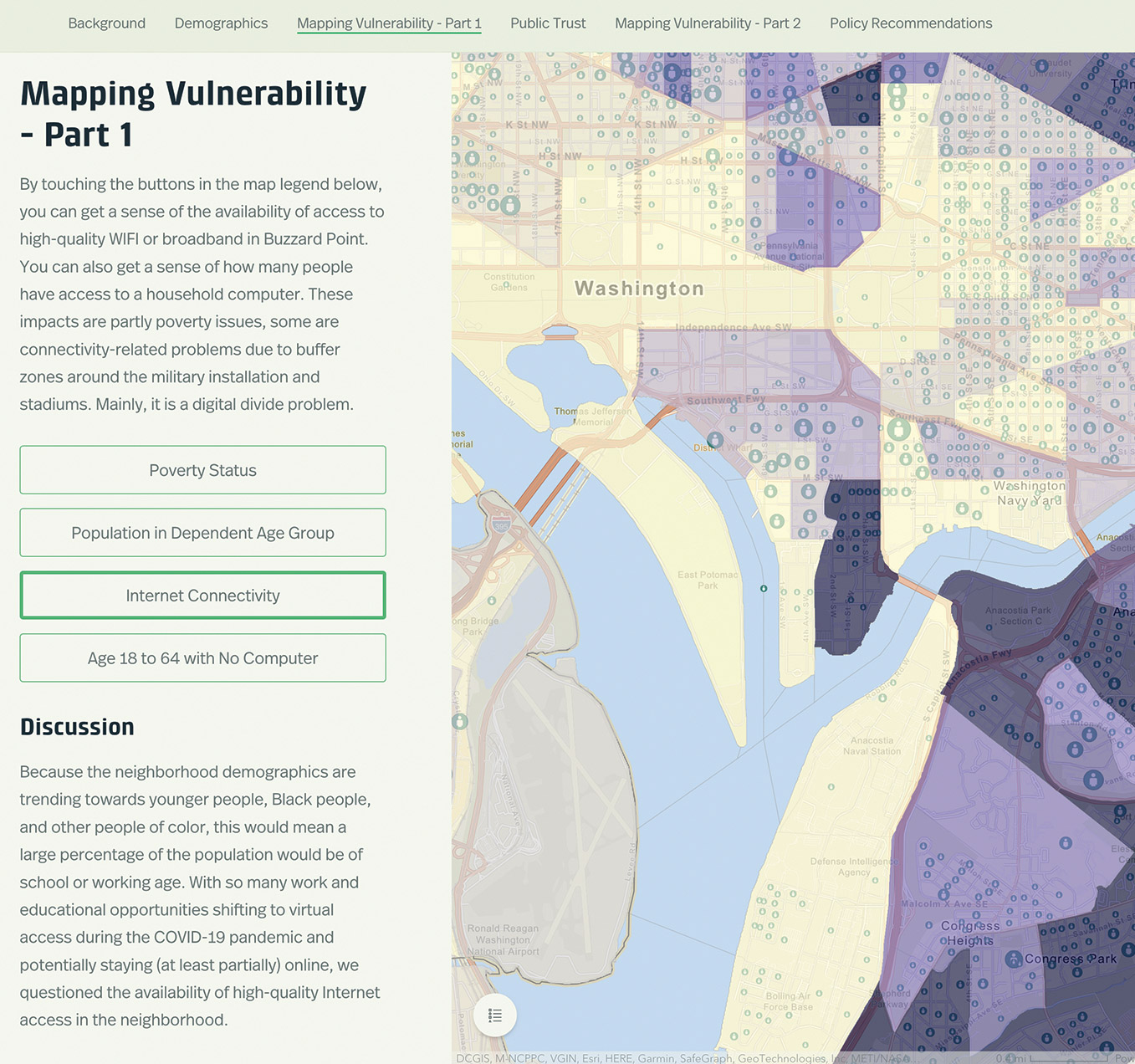

“As we’re going through the neighborhood working on the Wi-Fi issue, that’s when I came to the realization—I was like, this is a redlined neighborhood. They have urban heat issues, which have already been studied, but not by anyone from the community,” Sanders says. “It can’t be a coincidence that all of these things are happening at the same time.”

Jonathan Moore, RowdyOrb.it’s founder, sees the overlap as well.

“We’re recycling the same problems, but just in the digital world,” Moore says. “How do we make sure the biases that exist in normal society and the redlining that exists in normal society don’t exist online?”

But Sanders says she struggled to convince other colleagues and realized it would take more than anecdotal evidence—she needed research and proof to ensure that future policies would address these communities holistically, rather than cherry-picking issues in a way that would only chip away at the larger problem. The Undivide Project is an effort to gather that data, drawing further inspiration from RowdyOrb.it’s community-focused model.

THE UNDIVIDE PROJECT

In 2020, almost 20,000 households in Baltimore with school-age children did not have broadband or computers at home, according to a report from the Abell Foundation. Working with a cadre of other local nonprofit organizations and using funding from the Internet Society, locals trained through RowdyOrb.it installed antennas on city schools, community centers, and churches in Baltimore throughout the year. RowdyOrb.it has since received additional funding from United Way of Central Maryland, which is supporting new infrastructure that can also reach individual residences. The organization says its community hot spots now serve around 2,000 people each week, a number they expect to spike to 6,000 once the new installations are complete.