At the Wheeler Avenue Baptist Church in Houston’s Third Ward, the writing appeared to be already on the wall for Propositions A and B—a pair of school bonds totaling $4.4 billion for the Houston Independent School District. Voters showed up Tuesday telling poll greeters that their mind was already made up, announcing to campaigners they would not vote for the bond. “It’s a no go,” said one voter.

Despite the flood of glossy flyers, phone calls, and text messages sent to voters promising improvements to the district’s aging schools, promotional efforts bankrolled by more than $2 million from HISD and a charter school-backed PAC, 60 percent of early voters rejected the bond, a gap that election day voting is very unlikely to make up. Proclaiming “No trust, no bond,” its critics largely saw their vote as a referendum on the state takeover of Houston’s largest school district and state-appointed Superintendent Mike Miles, who has stirred up dissension among parents, teachers, principals, and other community members since he took control of the district in June 2023.

“In my 33 years as an educator, I’ve never known teachers to come out against a bond. I’ve never known the Republican Party and the Democratic Party to agree on anything. I’ve never seen so much community involvement and participation, mainly because we do not trust Mike Miles,” said Houston Federations of Teachers President Jackie Anderson. “You want us to give you a $4.4 billion check with no real community involvement or input. You stack the deck after you kicked off the elected [board]. … You just refused to work with us, parents, community at all, and this is the result of that. This failed bond is a result of his failure as a superintendent, his failed leadership.”

Cited as the largest bond proposal in state history, the measure would have allocated $2.3 billion for rebuilding and renovating 43 schools, $1 billion for lead remediation, security upgrades, and HVAC improvements, and another $1.1 billion to expand pre-K, build three new career and technical education centers, and make technology upgrades. Infrastructure upgrades of $3.96 billion were listed under Proposition A and $440 million for technology upgrades was listed under Proposition B on the ballot.

According to the election order, the bond would have added an additional $8.9 billion in debt (including $4.5 billion in interest) for the district over more than 30 years. And while the district promised there would be no property tax increases with the bond, the ballot stated “this is a property tax increase.” The tax rate would not change since there is already a current bond which has debt payments ending in 2043, but the new bond would have added more than $8.9 billion in debt through 2058.

Though simple opposition to higher taxes likely fuelled some votes, bond critics that the Texas Observer spoke to all said that they wanted to see improvements in the schools, but they did not trust Miles or the state-appointed board of managers to make those improvements, after Miles and the board alienated the community with a top-down approach in governing the district.

“They’ve [Miles and the board of managers] proven that over the last year and a half, they don’t care what the public thinks or says. They’re antagonistic to what the public thinks and says. So, why am I going to sign away our tax dollars for these people who are antagonistic to us?” Melissa Yarborough, a former teacher and parent of two children in the district, said.

Without a democratically elected board, Yarborough said there was no system of public accountability to oversee the bond. While there is a bond committee, its role is only to advise the superintendent.

“I’m waiting for an elected board that I can trust to listen to the people, to plan a bond that is reasonable, to take their time and get real public input on it, to really do thorough assessment of the schools, to see what the real needs are, rather than a rushed one, because that’s also wasteful.”

Like other critics, Yarborough told the Observer that in that short time period, Miles had already left the district in disarray, citing the mass exodus of experienced teachers and the firing of principals and staff last year. Yarborough left her teaching position at Navarro Middle School in the middle of the last school year after teachers there were increasingly asked to implement what she calls “militaristic” instruction with a “really tight control over every student’s movement the entire class period.” Even though the school was not part of the district’s “New Education System” reform program, Yarborough still had to teach from a powerpoint handed down by the district. When she raised concerns that the majority of the non-native English speakers in her class did not understand the powerpoint, a supervisor told her, “It doesn’t matter if the kids don’t understand it. It doesn’t matter if it’s not accessible to your beginner English learners. You have to follow it exactly as it is.”

Yarborough also moved her two children, ages 7 and 10 from Pugh Elementary School, after it lost 20 out of 28 teachers after being directed to join Miles’ “New Education System” program. She said of the program, “There’s no enthusiasm, there’s no care, they [her children] don’t see it as anything meaningful.”

Critics also noted Miles’ financial accountability record as another reason they rejected the bond, listing $470,000 of district funds Miles spent for a musical about his leadership, $356,000 spent on adult-sized spin bikes for elementary students, and $9 million wasted on library books after he closed school libraries, contributing to a $450 million shortfall after his first year in charge.

In a process the district called “co-location,” the bond would have also allocated $580 million to relocate students at eight schools to seven schools slated to be renovated nearby. Most of these schools are in Houston’s low-income communities of color.

“Co-location to me is just a cover-up word for [school] closure,” said Patrece Wright, a parent with an eight-year-old child in a HISD campus.

Wright is a PTO president at Blackshear Elementary School in the predominantly Black community of Third Ward. Her son had been attending the school since the age of three until Wright transferred him elsewhere after the school joined Miles’ “New Education System” program and she found the instruction her son was receiving was not on grade level and riddled with errors. Blackshear was one of the schools slated for closure, but the bond proposal included $8.4 million in upgrades for the school building. There were similar upgrades proposed for the other schools slated to be closed.

“My question is why are we putting $8.4 million in a school we’re no longer returning to,” Wright said, adding, “I believe they would sell it to a charter school.”

Critics also raised concerns that the scope and content of the proposal could change after the election. The school board can use unspent proceeds authorized in the election order for purposes beyond what was originally proposed after a public meeting, per state law.

“If Miles doesn’t follow what the bond plan is, who’s going to say anything? Sure as hell not the appointed board of trustees. They have not checked him on a single thing. They’re all just yes men and yes women who gladly rubber stamp whatever Mike Miles wants. So why would the people of Houston take on $4.4 billion of debt that they’re gonna have to pay for the next 30 years, when we don’t know that money is even going to be used for,” state House Representative Gene Wu told the Observer.

The bond prompted a rare instance of bipartisan opposition, albeit for slightly different reasons. Harris County Republican Party Chair Cindy Siegel told the Observer that the GOP organization did not take issue with Miles, but the bond was “too much, too soon.”

“This is way, way too much money at a time when HISD’s enrollment has declined about 10 percent. It should have been a maybe more phased approach, smaller amount, with high priority needs, and then get another year or two under their belt of improved scores and hopefully turn around the enrollment issue,” Siegel said, adding that there needed to be more community engagement if there is to be another bond proposal. “ It needs to take into account the students, and the parents need to have input into that.”

According to reporting by the Houston Chronicle, since February, the district had spent $1.48 billion in school funds to pay at least three different firms for the development and promotion of the bond: $730,000 to public relations firm Outreach Strategists for research, website development, and presentations to stakeholders; $325,000 to the consulting firm Kitamaba for project management, data analysis, and facilitating meetings; and $424,000 to the construction and project management firm Rice & Gardner for facilities assessment.

In a statement Tuesday night about the bond election results, Miles said: “In this instance, the politics of adults beat out the needs of our children. It’s unfortunate and wrong, but I want to assure you that it will not limit our ability to do the things that our students need.”

The Houstonians for Great Public Schools PAC spent more than $1.68 million to promote the bond. The group was founded by Veronica Garcia, the chief policy officer for Good Reason Houston, which supports mostly charter schools, Doug Foshee, business owner and former Kipp Charter School board member, and Ramon Manning, a chairman of a private investment firm in August when the district board of managers voted to place the bond on the ballot.

Early in October, a group of wealthy builders, contractors, and architects hosted a fundraiser asking donors to contribute as much as $100,000 to help promote the bond.

“They are a strong charter school supporting group in Houston, and they are wealthy business owners, architects, contractors, builders, people who could benefit from this bond getting passed, so that they can bid for contracts and get that money. It’s disgusting because they’re going against what the community clearly wants, which is a better bond with elected people to oversee that bond,” Yarborough said.

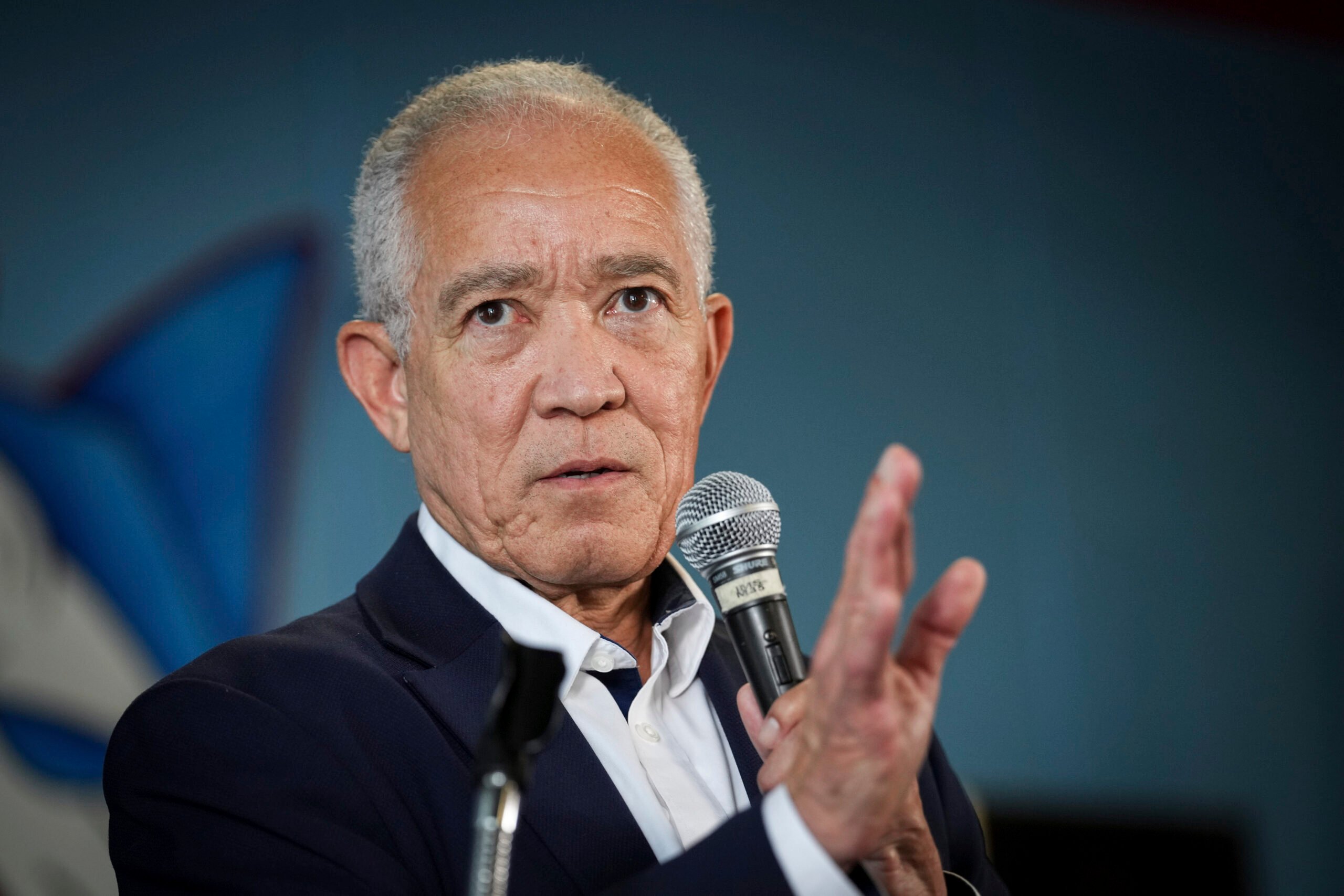

Former Houston mayor and newly elected Congressman Sylvester Turner told the Observer that the supporters of the bond revealed it was not for the schools or the students.

“I’m not convinced that some of the key players, like the governor, like the leadership at the state level, are really wanting to see public education succeed. So if you start off not wanting public education to work, and if you start off not wanting to invest in public education, then you come forth with these bond proposals, who are the bond proposals for?” Turner said.

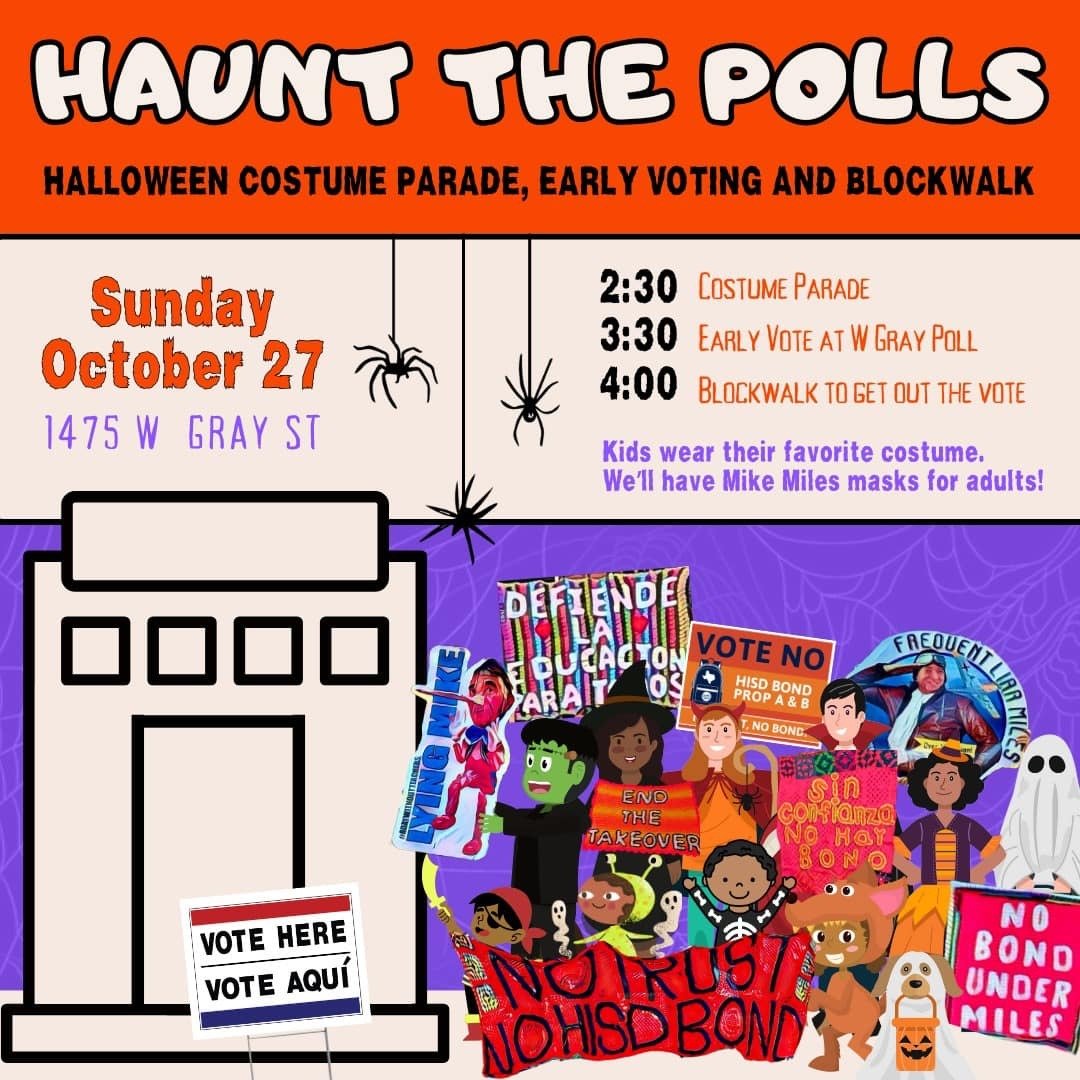

Leading up to the election, 24 Houston-area organizations and numerous elected officials spoke out against the bond, while parents in the district joined a knitting campaign or a Halloween parade to the polls to get Houstonians to vote against the bond.

Like other district stakeholders, Turner believes the widespread rejection of the HISD bond is a signal that the takeover needs to end.

“The takeover needs to come to an end. There needs to be a total reset,” Turner said. “You just can’t remove an elected board, put in place your people who are not accountable to the people in the area, and expect that model to succeed.”