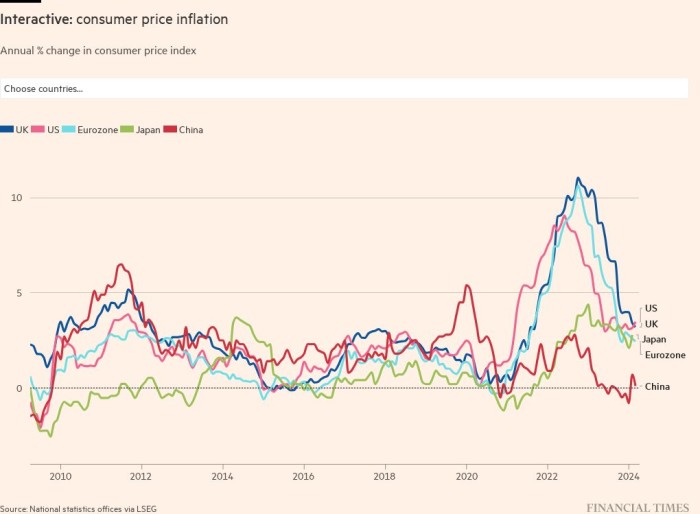

Inflation has hit its highest level in decades in many countries, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushing up energy and food prices and squeezing households’ real incomes.

Price pressures — and growth downgrades — have increased, triggered by the conflict. Some economists fear a return to the chronic inflation and recessionary environment of the 1970s.

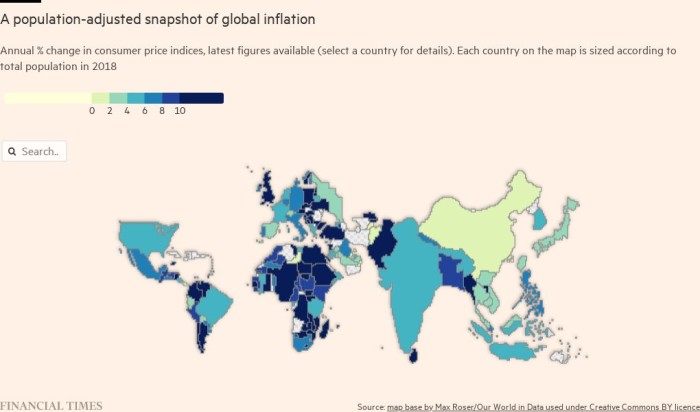

High inflation remains geographically broad-based. Consumer price growth has even started rising in Asia, a region that until recently had largely been an exception to the worldwide pattern.

As regular readers will know, this page provides a regularly updated visual narrative of consumer price inflation around the world, including economists’ expectations for the future. The latest figures for most of the world’s largest economies make for worrying reading, with price pressures surging to the highest level in many decades.

The rise in energy prices drove inflation in many countries even before Russia invaded Ukraine. Daily data show how the pressure has recently intensified on the back of a conflict that has led to Europe and the US banning, or considering bans, on Russian energy exports.

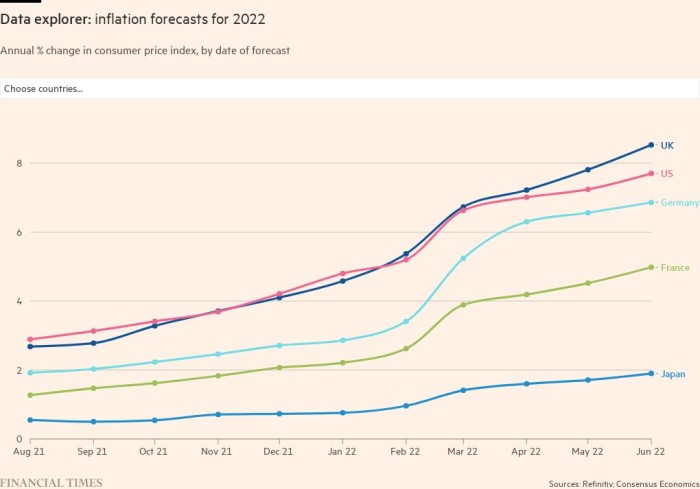

Leading forecasters polled by Consensus Economics have steadily revised up their expected inflation figures for 2022 and 2023.

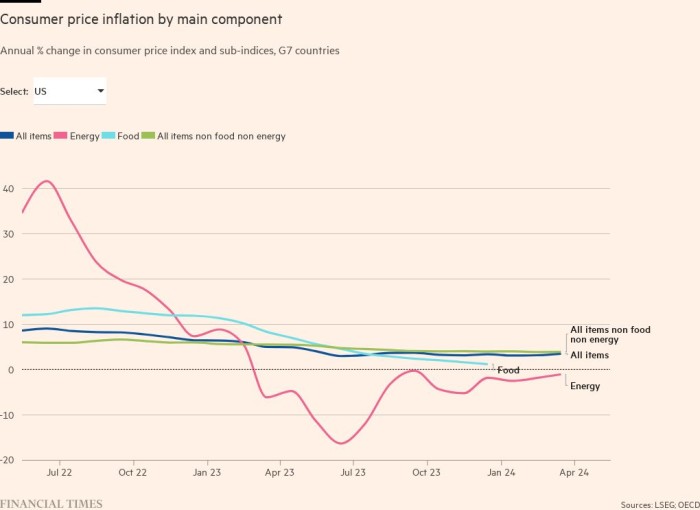

Higher inflation is also spreading beyond energy to many other consumer items, especially in countries where demand is strong enough for businesses to pass on higher costs.

Rising consumer prices present a challenge for central banks, not least those in G7 countries that have a price stability target of about 2 per cent. To reach that goal, central banks can adjust monetary policy to curb demand. But choking off demand by raising borrowing costs could exacerbate the squeeze on real incomes that has resulted from higher prices.

Rising prices limit what households can spend on goods and services. For the less well-off, that could lead to a struggle to afford basics, such as food and shelter.

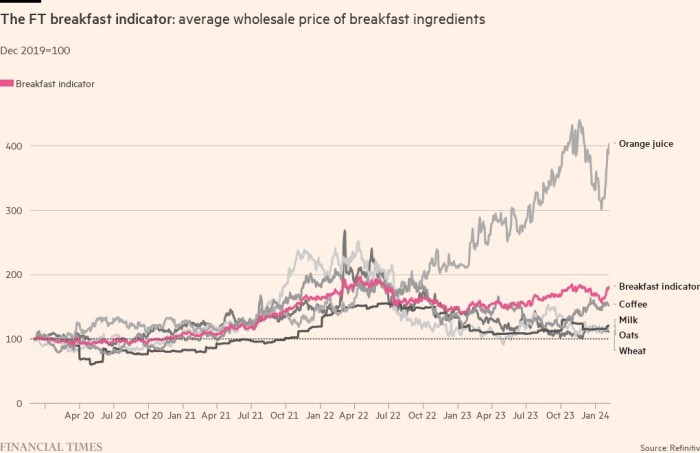

Daily data on staple goods, such as the wholesale price of breakfast ingredients, provide an up-to-date indicator of the pressures faced. In developing countries, the wholesale cost of these ingredients has a larger impact on final food prices; food also accounts for a larger share of household spending.

Another point of concern is asset prices, especially for houses.

These soared in many countries during the pandemic, boosted by ultra loose monetary policy, homeworkers’ desire for more space and government income-support schemes.

The key debate among policymakers and economists remains focused on how long high inflation will last. A few months ago, many expected the surge to be too shortlived for monetary policy to have much of an impact, with the effect of higher rates taking time to seep through into economies. However, the conflict in Ukraine — along with signs that inflationary pressures have become more broad based — have exacerbated fears that inflation will prove stickier than hoped.

Markets’ expectations for inflation over the next five years are generally rising, suggesting support for the view that the pain businesses and households are experiencing will endure.