If he wins the presidential election in October, it will go down as the political comeback of the decade — if not the century. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a former shoeshine boy and metalworker, benefited from an economic boom as Brazil’s president and left office in 2010 with an approval rating above 80 per cent.

“I was aware that if I reached the presidency of Brazil and my government didn’t work out, a worker would never again be able to think about becoming president,” he says in an interview with the Financial Times at his campaign’s media hub, a hip office space in a fashionable neighbourhood of São Paulo.

Under his anointed successor, Dilma Rousseff, however, the economy plunged into a brutal two-year recession — partly as a result of policies introduced in his second term. It has struggled to generate strong, sustained growth ever since.

The leftwing Workers’ party (PT) he has dominated for four decades was revealed to have been at the centre of a massive graft scheme while Lula and Rousseff were in office. The US Department of Justice described it as the “largest foreign bribery case in history”.

As the country became enraged at the extent of the corruption under PT rule, Lula was jailed in 2018 on graft charges — spending 580 days in a federal prison. While he was in jail, Jair Bolsonaro, an anti-establishment far-right former army captain, won the presidency.

Yet after being released in 2019 on a procedural issue, Lula is now on the verge of a stunning second chance. According to the opinion polls, the 76-year-old, who remains an icon of the Latin American left, is a strong favourite to win back the presidency in October from Bolsonaro.

With many Brazilians seemingly exhausted by Bolsonaro’s mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic and endless culture war antics, Lula — dressed in a smart navy blue suit and red-striped tie — is trying to persuade people that he is a statesman who can bring political stability and haul the country out of the economic hole it has been in for much of the past decade.

“I am very sad because 12 years after I left the presidency, I find Brazil poorer,” he says. “I find more unemployment, more people going hungry and Brazil with a government that has very low credibility at home and abroad.”

Lula greets his interviewers like old friends and the conversation includes an animated discourse about the relative merits of Brazilian and British football, ending with his conclusion that the sport has been the biggest winner from globalisation.

Although there are still three months to go before the first round of voting on October 2, Lula is leading in some polls by a margin of 10 percentage points or more. “It’s Lula’s election to lose,” says Oliver Stuenkel, a political expert at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo. “It’s incredibly difficult for Bolsonaro to be a competitive candidate.”

With their strong bases of loyal supporters, Lula and Bolsonaro dominate the political landscape, leaving little space for challengers. But both are also divisive figures who generate a lot of resentment.

Indeed, they have fed off each other. Lula’s insistence that the corruption scandal was largely a conspiracy against his party generated a deep well of cynicism among many voters, opening the way for a political outsider. Bolsonaro won in 2018 by presenting himself as the anti-Lula candidate.

Now Lula is positioning himself as the antithesis of Bolsonaro, a politician known for tirades against women, gays and environmentalists. After nearly four years of the current president, who champions conservative values and gun ownership, Lula says Bolsonaro “has become a pariah of humanity”.

His capacity to connect with people stands in contrast to Bolsonaro, who, according to pollsters, alienated voters through his reckless attitude to Covid and his lack of empathy for the 674,000 Brazilians who lost their lives.

For the business community, the question is: if he does win, which version of himself will Lula govern as — the economic pragmatist of his first years or the more ideological interventionist who emerged during his second term?

Lula gives away few specifics about his plans: however hard you try to point his gaze towards the future, he prefers to recall past triumphs and his dealings with former leaders such as Tony Blair, Jacques Chirac and Gerhard Schroeder.

But he wants to be seen as a safe pair of hands. Lula stresses “three magic words in governing”: credibility, predictability and stability. At his age, he adds, he is “more experienced, more seasoned and with a much greater desire to get it right”.

Looming recession

Lula’s first election to the presidency in 2002 was marked by a piece of great political fortune: it coincided with a long rally in global commodity markets that was sparked by rapid growth in China. Along with several other resource-rich countries in the region, Brazil’s economy soared.

If he wins again this October, however, Lula will be faced with a very different environment: a potential global recession and a stretched budget that leaves little room for discretionary spending.

Brazil is set to grow between 1 and 2 per cent this year and unemployment has fallen below double digits for the first time since 2016, but inflation is a big worry. Prices are rising 12 per cent a year, even though the central bank has pushed up interest rates to more than 13 per cent. A generous fiscal stimulus during the pandemic reduced deprivation but was withdrawn soon after.

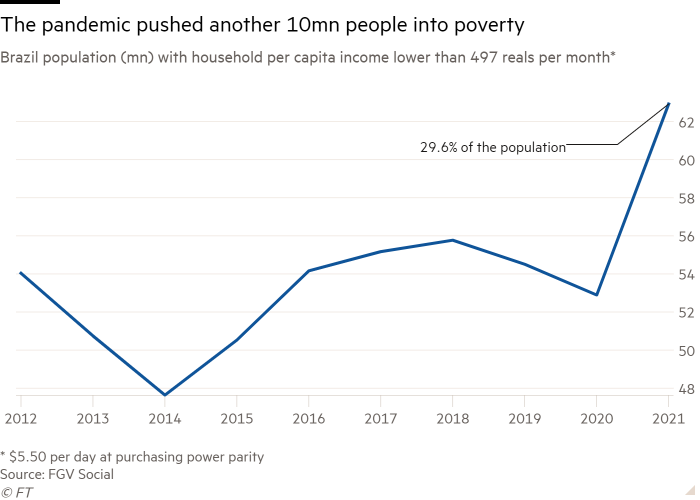

Extreme poverty jumped by more than a third last year to 14 per cent, according to FGV Social. The research centre said 36 per cent of the population did not have enough money for food, based on a Gallup poll, in a country that is one of the world’s biggest agricultural exporters.

Ahead of the ballot, Bolsonaro is betting on bigger handouts to the poorest and is hoping to push through fuel subsidies for truckers and taxi drivers.

Lula prefers soaring rhetoric over policy detail. He becomes emotional when he speaks about his own deprivation as a child. “I didn’t eat bread until I was seven,” he recalls. “I often saw my mother standing by the stove with nothing to make for lunch or dinner.”

He says he will do away with a constitutional cap on public expenditure and insists that social spending is an investment, not a cost. “When poor people stop being very poor and become consumers of health, education and goods, the whole economy grows,” he says.

Yet he also dismisses doubts about his commitment to fiscal responsibility. “I learnt very young from my illiterate mother that I couldn’t spend more than I earned.” He points to his choice of vice-president, Geraldo Alckmin, a centrist leader who once ran against him, as evidence of moderation.

Lula says he will name a finance minister who is not an economist but a skilled politician advised by a group of experts, as he did in his first term. He wants to review labour reforms enacted after the PT left office and says he will overhaul the tax regime — a move the Bolsonaro government attempted but failed — to make the rich pay more.

Thomas Traumann, a political commentator who worked in the Rousseff administration, believes Brazil can expect a mixture of Lula’s pragmatic first term and the greater state interventionism of his second term. But he dismisses fears of radicalism.

“The main difference from Lula today and the Lula who was president is now he centralises decisions much more than before,” says Traumann. “He trusts less people. You can count them on one hand.”

Lula has little sympathy with business people who worry about possible extremism and criticise him for a lack of new ideas. “The Brazilian elite has a slave-owning mentality,” he says, referring to the criticism he received when his party formalised the employment of domestic workers. “You know what they said here in Brazil when the traffic was bad? That it’s a disgrace that Lula allowed poor people to buy cars.”

Despite his hostile rhetoric, Brazil’s economic elite is not panicking at the idea of Lula’s return to power. The constant political turbulence of the Bolsonaro administration has unnerved the business community despite the implementation of some economic reforms, such as limits on public sector pensions and some privatisations. And Lula is a known quantity. “Lula is not an institutional threat,” says one senior banker. “We’ll lose some quality in economic policy but it won’t be a reversal.”

Alberto Ramos, chief Latin America economist at Goldman Sachs, is more concerned. “The public sector in Brazil is astonishingly inefficient and Lula wants to empower it — and that’s not a good thing,” he says.

‘The poor were seen’

Lula’s greatest strength as a candidate is the memory of the rising prosperity during his time in office.

Half an hour away from his campaign office, along a street of tall, makeshift buildings painted in bright colours, local activists have used the pandemic as an opportunity to launch a social enterprise hub that provides everything from vegetable growing classes in an allotment for women facing domestic violence to microcredit. In this favela, or shanty town, named Paraisópolis, some 100,000 people live on the margins of São Paulo. Many recall Lula’s time in office fondly. “The poor were seen,” says Gilson Rodrigues, a community leader.

Like others, he says things worsened during the pandemic in a neighbourhood where ambulance drivers fear to enter. No one has forgotten the corruption during the PT years. But Lula is seen as a leader who transcends his party and is not motivated by personal gain. “Lula stole but gave to the poor, Bolsonaro stole but gave to the rich,” quips a young delivery driver, reflecting a popular perception.

During the Lula years, Brazil sharply reduced poverty through social welfare programmes such as Bolsa Familia — a cash transfer programme for the poorest.

Under Rousseff, however, the reach of the Brazilian state into the economy expanded further as interventionist policies took hold. Her government’s meddling and years of loose fiscal policy were blamed for soaring inflation and Brazil’s worst recession on record.

The PT was also at the centre of Latin America’s biggest corruption scandal, known as Lava Jato (Car Wash), centred on kickbacks for contracts with state-controlled oil group Petrobras. With her popularity in the doldrums, Dilma was impeached in 2016.

By the end of the Car Wash investigation, several hundred businessmen and politicians had been convicted. Lula himself was found guilty of receiving bribes in the form of favours related to a beachside apartment and a country house. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison, eliminating him from an expected run in the 2018 presidential race.

Released from prison pending a new appeal, his conviction was overturned by the supreme court in April 2021 on a jurisdictional technicality. Lula has always insisted that the investigation was politically motivated. The fact that the judge who initially convicted Lula, Sergio Moro, then went on to serve as Bolsonaro’s justice minister added weight to that view.

“If there was corruption, it was investigated and people paid a price for having paid a mistake,” Lula says. “What happened in Brazil was a political action to try to destroy the image of many people and prevent me from becoming president in 2018.”

Bearing arms

Inside the cramped Brasília office of Eduardo Bolsonaro, third son of the president and a congressman for São Paulo state, are the trappings of his family’s rightwing world view: miniature figures of Donald Trump, the former US president, a replica revolver and a framed copy of the second amendment of the American constitution guaranteeing the right to bear arms. A tall, smartly dressed former federal policeman, the young Bolsanaro rails against the supreme court and mainstream media, who he says are clamouring for the return of Lula.

He insists the polls are wrong and that the race is tied. His father, he says, is a “freedom fighter” who was one of the few world leaders to stand against Covid restrictions, while Lula is a dictator in the making.

Will his father concede if Lula prevails? Bolsonaro has said that only God could remove him from power. Eduardo repeats the president’s claim that the long-established electronic voting system must be changed before the election but will not comment on the consequences if it is not. Lula himself dismisses suggestions of a post-election crisis similar to the US Capitol insurrection or military intervention. “Bolsonaro is someone who bluffs,” says Lula. The president may want a coup but “he would be on his own”.

Brazil’s allies will be watching closely. Lula promises to bring the country back to the global stage as an environmentally responsible and socially aware major developing power. He says he will introduce a new border force and sharply reduce deforestation, citing his success in the first term as proof of his ability to deliver. “We have to make the preservation of the Amazon a top priority.”

His views on geopolitics will be less welcome, with the west now enmeshed in a new cold war with Russia and China. Lula has previously criticised Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as partly responsible for the Russian invasion. But he insists that Brazil will not be drawn into taking sides in the Ukraine war, and that negotiations must be attempted. He criticises the US for its “lack of patience” in seeking peace and sees himself as a potential negotiator who can speak to all sides, including China, Brazil’s biggest trading partner, and the US, its ally and biggest foreign investor.

A victory this October would hand him the opportunity to define his legacy for posterity. He has said he will not run for a fourth term. Veteran pollster Carlos Augusto Montenegro says that to secure his place in history, Lula should appoint a broad cabinet of experts and attempt real reforms to Brazil’s dysfunctional political system.

Lula insists that his immediate priority will be improving social conditions. Can he slay Brazil’s twin demons of hunger and poverty? Lula answers with a gruff chuckle: “If I manage that, my dear friend, I will go to heaven.”