This story is the first of a two-part series by Public Health Watch and The Texas Tribune. It is co-published by Grist.

Danny Hardy was sitting in the third-row pew at Deer Park First Baptist Church when the cellphones began buzzing in unison. Several men quickly shifted in their seats — all of them first responders or employees at one of the dozens of nearby refineries and chemical plants.

Hardy, a retired police officer and head of the church security team, wasn’t alarmed. After living in the Houston suburb of Deer Park for nearly 40 years, he was accustomed to the sight of refinery flares burning in the night, the occasional stench of chemicals and the sound of sirens wailing in the distance. Deer Park was nestled in the heart of North America’s petrochemical industry. These things were to be expected.

But as ripples of conversation spread through the congregation, it became clear that this emergency alert — on Sunday, March 17, 2019 — was different. After a few tense moments Wayne Riddle, a former mayor, stepped onstage and addressed the crowded worship center.

There had been an accident. A facility housing millions of barrels of volatile chemicals was burning a little more than two miles away. City officials had issued a shelter-in-place advisory.

Hardy looked out a window and saw a towering plume of ink-black smoke blanketing the sky. He instructed a team of 30 deacons and volunteers to shut off the air-conditioning system and guard the exits. Everyone needed to stay inside, safe from whatever fumes might be lurking outside.

The choir sang a worship song to calm the parishioners: “Lift your voice / It’s the year of jubilee / And out of Zion’s hill / Salvation comes.”

Mark Felix for The Texas Tribune / Public Health Watch

Four hours later and 1,000 miles away in Boulder, Colorado, Ken Garing got an email about the mushrooming chemical fire in southeast Texas.

For 30 years, Garing had worked as a chemical engineer for a branch of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that investigates high-stakes cases of industrial pollution. His back stiffened when he saw that the blaze was at Intercontinental Terminals Company, or ITC, in Deer Park.

Garing had visited the 265-acre chemical storage facility twice, in 2013 and 2016. Both times he’d left shaken by what he’d seen. Worrisome amounts of chemicals were leaking into the air from dozens of ITC’s massive tanks, including an outpouring of benzene, a carcinogen that can cause leukemia.

“I remember thinking, ‘Holy cow.’ They had by far the highest benzene numbers we’d ever seen inside a facility,” he said. “Something bad was going to happen at ITC. It was just a matter of time.”

A 10-month investigation by Public Health Watch found that Garing was one of many state and federal scientists who documented problems at ITC long before catastrophe struck. The fire didn’t just punctuate years of government negligence — it revealed regulatory failures familiar to communities that experience chemical disasters, including the recent train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio. The pattern is a common one: State and federal officials know for years of a looming danger but repeatedly fail to correct it. And then, after an accident occurs, they fail to adequately protect those who are harmed.

The story of how this pattern unfolded in Deer Park, a tight-knit city of 30,000 and the self-proclaimed “Birthplace of Texas,” is based on thousands of pages of state and federal documents, on investigative reports and pollution data from the EPA and on eyewitness accounts from residents. It also draws on extensive interviews with a handful of retired government regulators who tried to sound the alarm about ITC years ago and are speaking out now in the hope of preventing future disasters.

ITC’s 227 chemical storage tanks sit on the northern outskirts of Deer Park like giant, white monuments to Texas’ powerful petrochemical industry. The facility is owned by Japan-based Mitsui Group, one of the world’s largest corporations. It stores and distributes toxic chemicals, noxious gases and petroleum products essential to the region’s thousands of chemical plants and refineries, moving the products from freighters to railways, barges to pipelines, tankers to refineries. It has more than 20,000 feet of rail lines, plus five shipping docks and 10 barge docks that back up to the Houston Ship Channel. Downtown Houston is just 17 miles away.

The petrochemical industry has been intertwined with Deer Park for nearly 100 years. It is the city’s largest employer and a major philanthropic source for civic activities. It has especially close ties with Deer Park’s schools, which, along with well-paying industry jobs, are key draws for families. When the town’s school district was created in 1930, its board met at the local Shell refinery.

Mark Felix for The Texas Tribune / Public Health Watch

Deer Park has plenty of reasons to be loyal to industry. But in July 2004, Tim Doty and 14 other scientists from the state’s environmental regulatory agency — the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ — were focused on the risks industry might pose to the town.

The TCEQ was barely a decade old at the time, but it was already under heavy fire from environmental leaders — especially Houston Mayor Bill White, a Democrat whose city was fighting a losing battle against air pollution. The American Lung Association named Houston the nation’s fifth smoggiest city that year, and emissions from Deer Park and neighboring towns contributed to the problem. White wanted the TCEQ to toughen regulations and increase fines for repeat offenders of the federal Clean Air Act.

Doty had been tracking industrial emissions since 1990, when he went to work for the Texas Air Control Board, an agency that preceded the TCEQ. His ability to interpret complex chemical readings had made him one of its sharpest investigators. His dogged commitment made him one of its toughest.

Doty’s mobile monitoring team had taken chemical readings around ITC before.

In 2002, his scientists found startling levels of benzene and other dangerous chemicals outside the facility, including toluene, which is found in nail polish and explosives, and 1,3-butadiene, a carcinogen used in plastic and rubber products. The emissions were so strong that three of Doty’s scientists experienced burning throats, burning noses and watering eyes.

But the incident didn’t lead to any fines. The TCEQ, the state’s primary enforcer of the federal Clean Air Act, penalized ITC only once between 2002 and 2004 — for equipment problems, not chemical leaks. Most of the meager fines the company faced in that period came from the Federal Railroad Administration and the EPA.

Just six months before Doty’s team arrived in Deer Park in July 2004, ITC had illegally released 101 pounds of 1,3-butadiene into the air. But no fines were issued and 16 days later, the TCEQ gave ITC permission to install an additional tank of 1,3-butadiene. It also renewed the facility’s 10-year chemical permit — one of two key permits required of any company that emits pollution as part of its routine operation.

The TCEQ scientists spent almost a week that July combing Deer Park and surrounding communities for illegal emissions. For 13 to 14 hours each day, they triangulated emission sources along the peripheries of various facilities.

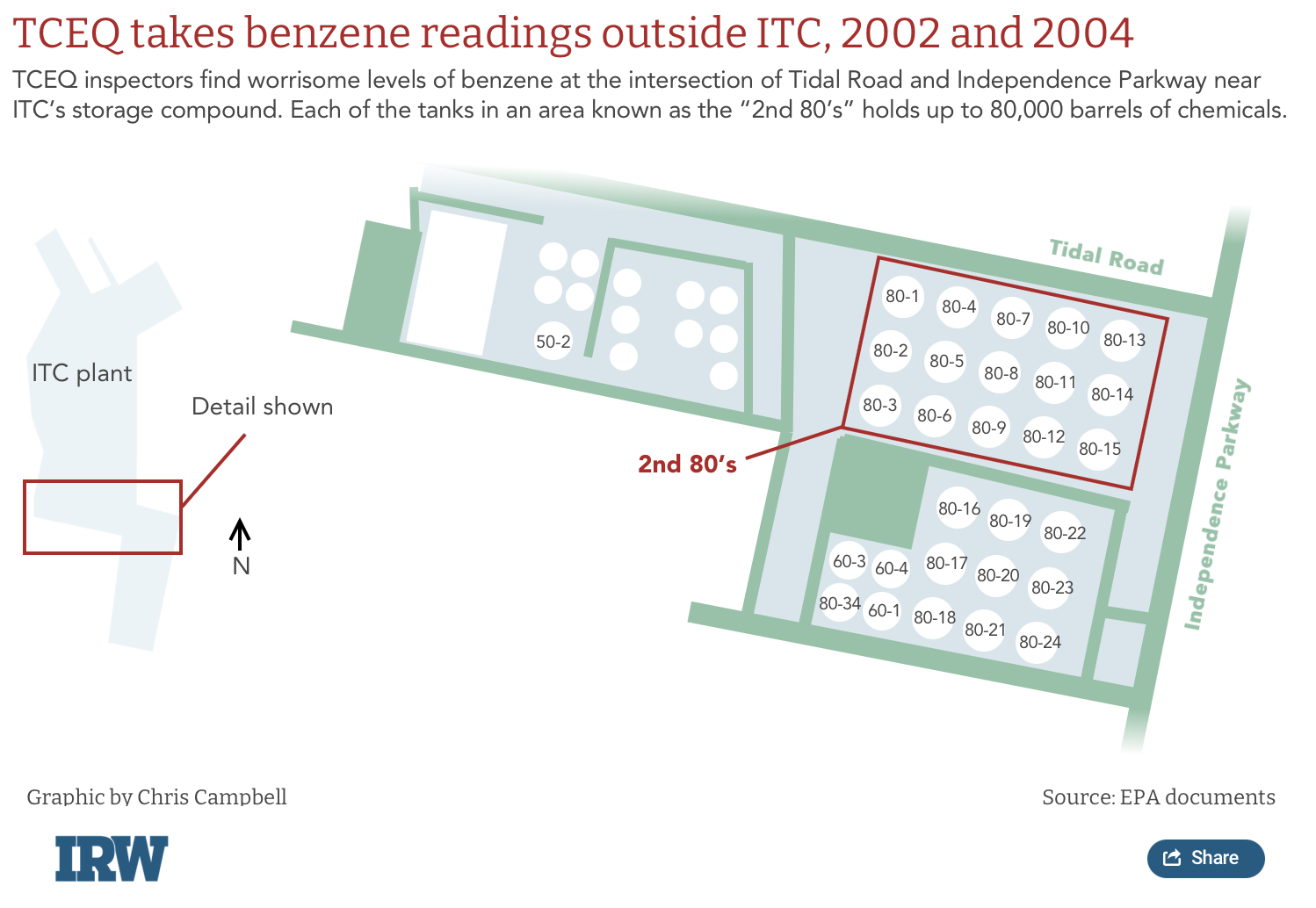

The corner of Tidal Road and Independence Parkway quickly became their top priority.

Two hazardous waste facilities and a chemical plant that produced chlorine and caustic soda, which is used in soaps and to cure foods, sat nearby. But ITC’s storage compound dominated the intersection. It was filled with tanks housing volatile fuels, including gooey leftovers from the refining process. Each tank had a number that allowed ITC — and regulators — to keep track of its emissions and compliance record over the years. The tanks in this corner, known as the “2nd 80’s” because each could hold up to 80,000 barrels of product, were 80-1 through 80-15. All of them were built in the 1970s.

That intersection “was literally ground zero for benzene,” Doty said. “There were many chemical sources around there, but ITC was right in the middle of it all. It was one of our main focuses.”

The scientists used handheld vapor analyzers to take rough measurements of chemicals in the air. They used small, metal canisters to trap air samples that would later be tested at the TCEQ laboratory. But their biggest weapons were their 16-foot box vans. The vans were outfitted with 30-foot weather masts that allowed them to track wind direction and small ovens that rapidly analyzed air samples by burning off chemicals one by one.

The scientists’ findings led to a follow-up inspection by the TCEQ. They were also summarized in an internal memo to seven agency officials, including the directors of the offices of compliance and enforcement and air permitting.

“Elevated levels of benzene and 1,3-butadiene” had been detected near the intersection of Tidal Road and Independence Parkway, the memo said. ITC, the suspected culprit, had been issued a notice of violation, a document that lists problems a company is required to address. According to the memo, ITC had released a sustained concentration of 720 parts per billion of benzene over the course of an hour, a “violation of their permit.”

But again the TCEQ let ITC off the hook.

The company said it had fixed the faulty tanks and no further action was taken. A year later, the TCEQ gave ITC permission to install 48 additional tanks.

To Doty, these decisions were just more examples of the TCEQ bending to industry rather than protecting the public.

“It was frustrating. My team was always trying to do the right thing,” he said. “Whether TCEQ actually followed up with any meaningful action, well, that’s a different issue.”

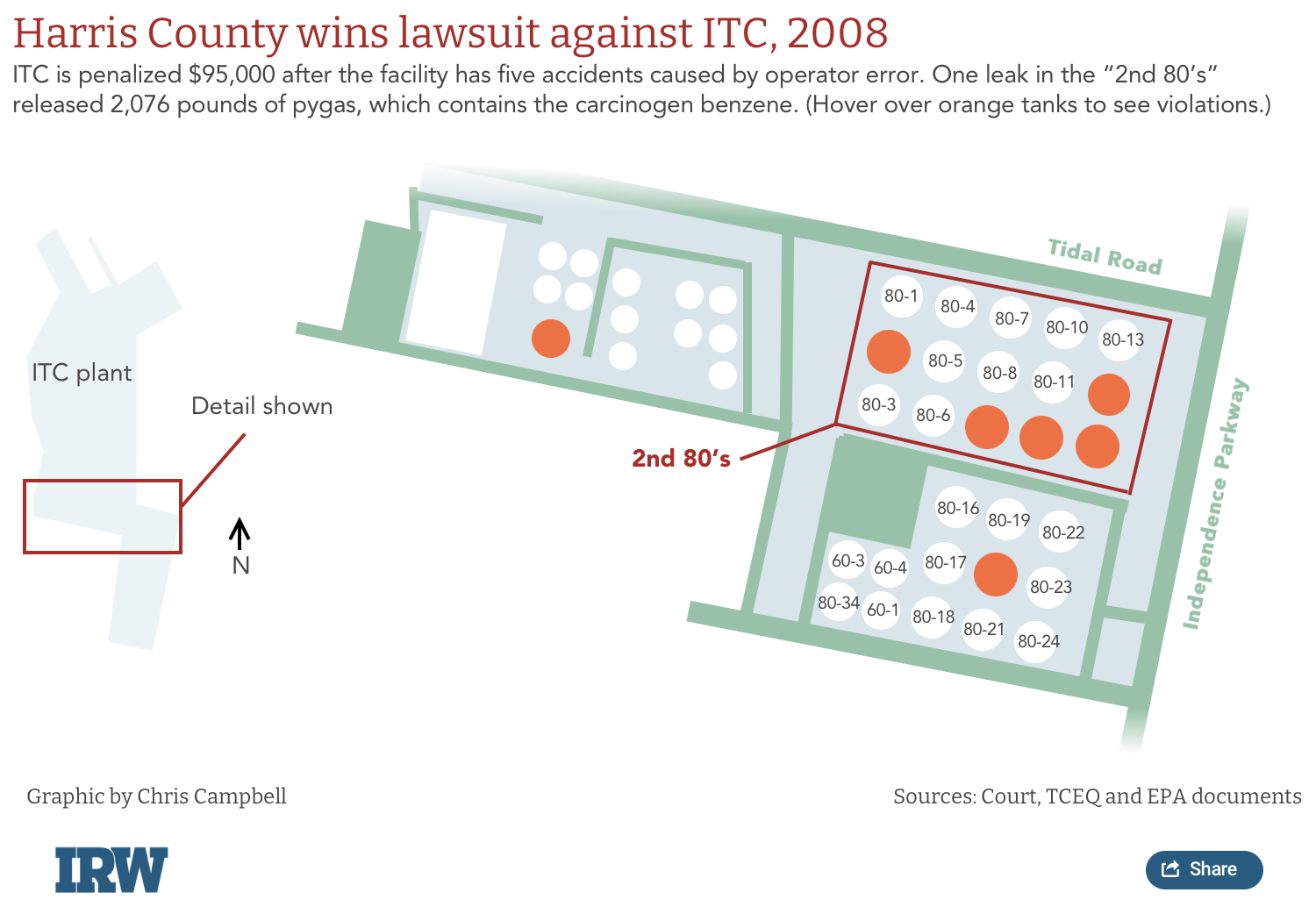

In December 2006, another problem cropped up in ITC’s “2nd 80’s.”

Emergency responders rushed to Tidal Road after a pressurized valve malfunctioned, spewing 2,076 pounds of pyrolysis gasoline, or pygas, into the air, onto the ground and into a water-filled roadside ditch.

Pygas is rich in benzene and toluene. Exposure to these chemicals can cause symptoms ranging from dizziness and irregular heartbeats to kidney damage. In extremely high concentrations they can lead to death.

Harris County investigators closed Tidal Road for 13 hours as they managed the contaminated area and gathered air and water samples. Harris County includes Houston, Deer Park and other industrialized towns.

Liz Moskowitz for The Texas Tribune / Public Health Watch

County officials pounced on the accident. They’d grown frustrated by the TCEQ’s leniency and were beefing up their own air monitoring and investigative efforts.

Harris County sued ITC over the pygas leak, alleging that the facility had committed six separate violations of the Texas Clean Air Act and the Texas Water Code. In their petition, the prosecutors said they were confident the case would warrant a penalty as high as $150,000 “because of the compliance history of ITC.”

Harris County updated its petition less than six months later after another ITC incident. In a span of just four minutes, nearly 1,800 pounds of 1,3-butadiene escaped from tank 50-2, the tank’s fourth emissions violation in as many years. It was located in a section of the facility adjacent to the “2nd 80’s” near Tidal Road, where Tim Doty and his team of TCEQ scientists had recorded high levels of benzene three years earlier.

Since then, Doty’s team had made four more week-long investigative trips to Deer Park. Each time it left with new data about ITC’s troubling benzene emissions. Doty described the problems in his post-trip reports.

“I created detailed narratives and stories that anybody curious about what was happening at ITC — say, a journalist — could follow up on,” he said. “We were determined to show that ITC’s problems were consistent. They weren’t one-time events.”

Again, the TCEQ didn’t issue any penalties.

In 2008, ITC settled the lawsuit with Harris County for $95,250 for five chemical leaks caused by operator error. The company agreed to abide by environmental laws and implement better management practices — a promise it failed to keep. After another chemical accident caused by operator error the following year, Harris County sued again. This time ITC settled for $90,000.

While ITC was fending off regulators, Elvia Guevara was settling into her new home four miles away from its chemical tanks.

The comfortably middle-class community of Deer Park was everything she and her husband, Lalo, had hoped it would be when they moved there in 2008. The Houston suburb was small, intimate and safe. Its planned neighborhoods were lined with clean streets, large yards and spacious two-story homes. And its proximity to petrochemical facilities meant shorter commutes to work.

Mark Felix for The Texas Tribune / Public Health Watch

Guevara managed around-the-clock logistics for a nearby chemical company. Her husband was a railroad tech manager who repaired rail lines near ITC. The industry had been good to them. It helped them move from Pasadena, a less-affluent neighboring city, and put food on the table for their three sons, Eddie, Anthony and Adrian.

“We didn’t focus on the possibility of chemical leaks and things like that,” Guevara said. “For us, it was normal to live in a community surrounded by chemical companies.”

Unbeknownst to Guevara, the EPA — the agency tasked with making sure Texas properly regulated those companies — was entering a period of turmoil. A determined regulator, Debbie Ford, had a front-row seat.

Ford arrived in Dallas in August 2008 as an air enforcement inspector for EPA Region 6, which oversees federal environmental regulations in Texas, Louisiana and three other states. She’d spent most of her life in Lake Charles, Louisiana, where her father was the medical director at a refinery. After earning a master’s degree in environmental science, she went to work for the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ.

Ford’s ability to interpret complicated chemical permits and memorize labyrinthine air pollution regulations shot her up the agency’s ranks. Within six years, she was the senior air technical inspector of her regional office and one of the DEQ’s most respected technical experts, especially when it came to chemical tanks.

But Ford’s rigorous approach earned her a reputation as a “pot-stirrer” in a state that, like Texas, is known for its lenient approach to enforcement. Rather than yielding to the political pressure and regulatory tiptoeing that often steered the agency, Ford pressed on — often to her bosses’ chagrin.

“To me, it was simple: The regulations are in place and everybody’s supposed to follow them,” Ford said. “But some companies were able to skirt the rules and receive lax permits thanks to their influence in the state.”

Ford thought that joining the EPA would give her a better chance to make an impact. But she soon learned that the agency’s powers under the Clean Air Act are limited. The act makes the EPA responsible for overseeing the implementation of federal regulations, but it gives states most of the responsibility for enforcing them. Like parents trying to corral their sometimes-rambunctious children, the EPA’s 10 regions are often forced to cajole and compromise with their state partners.

Several current and former EPA officials told Public Health Watch that Region 6 took a “go-along-to-get-along” approach when dealing with industry-friendly states like Texas and Louisiana. They said its reputation for going light on violators of the Clean Air Act was well-known at the other EPA regions — and even at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Ford was unprepared for Region 6’s lax attitude. When she arrived at its office in downtown Dallas the first time, she said no assignments had been prepared for her and she was given only minimal information about the ever-evolving federal air pollution regulations she was expected to enforce. She said a co-worker regularly slept at a desk nearby and that she once overheard a higher-up whisper to another boss, “Don’t let her find out too soon how little we do here.”

When Public Health Watch asked Region 6 about this exchange, the agency said it “cannot verify an overheard statement.”

Ford was shocked by what she saw.

“I just kept thinking, ‘What the hell have I gotten myself into?’”

Ford felt a bit hopeful in 2009, when President Barack Obama chose Alfredo “Al” Armendariz, an engineering professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, to lead Region 6.

Environmentalists rejoiced because Armendariz was known for criticizing state regulators about their weak approach to enforcement. But officials and industry groups in Texas strongly opposed his appointment. They were especially angered by a paper he had written before he took the job. It showed that natural-gas drilling in the Dallas-Fort Worth area created nearly as much smog and greenhouse gases as the cities’ gridlocked traffic.

Emil T. Lippe for The Texas Tribune / Public Health Watch

Eight months after his appointment, Armendariz sent his bosses in Washington a 44-slide PowerPoint presentation asking for more resources for the Dallas office. His argument was clear: Region 6 had by far the most petrochemical facilities in the country. But it had the sixth-smallest staff among the 10 regions and was unequipped to properly enforce the Clean Air Act.

In the spring of 2011, more than 25 Texas officials, including then-Gov. Rick Perry, created a task force to combat what they saw as increasingly intrusive EPA policies. In 2012 a video emerged that cost Armendariz his job. In it he compared his enforcement philosophy to Roman crucifixions. By making an example of bad actors, he said, the EPA would drive the rest of the industry to police itself.

Armendariz apologized for his word choice, but the damage had been done. The TCEQ described his comments as “outlandish” and “unacceptable and embarrassing.” Perry tweeted that Armendariz’s statements were “another reason to all-but-eliminate EPA.”

Armendariz stepped down four days later.

Despite the turmoil at the top of Region 6, the staff in the air enforcement division pushed on.

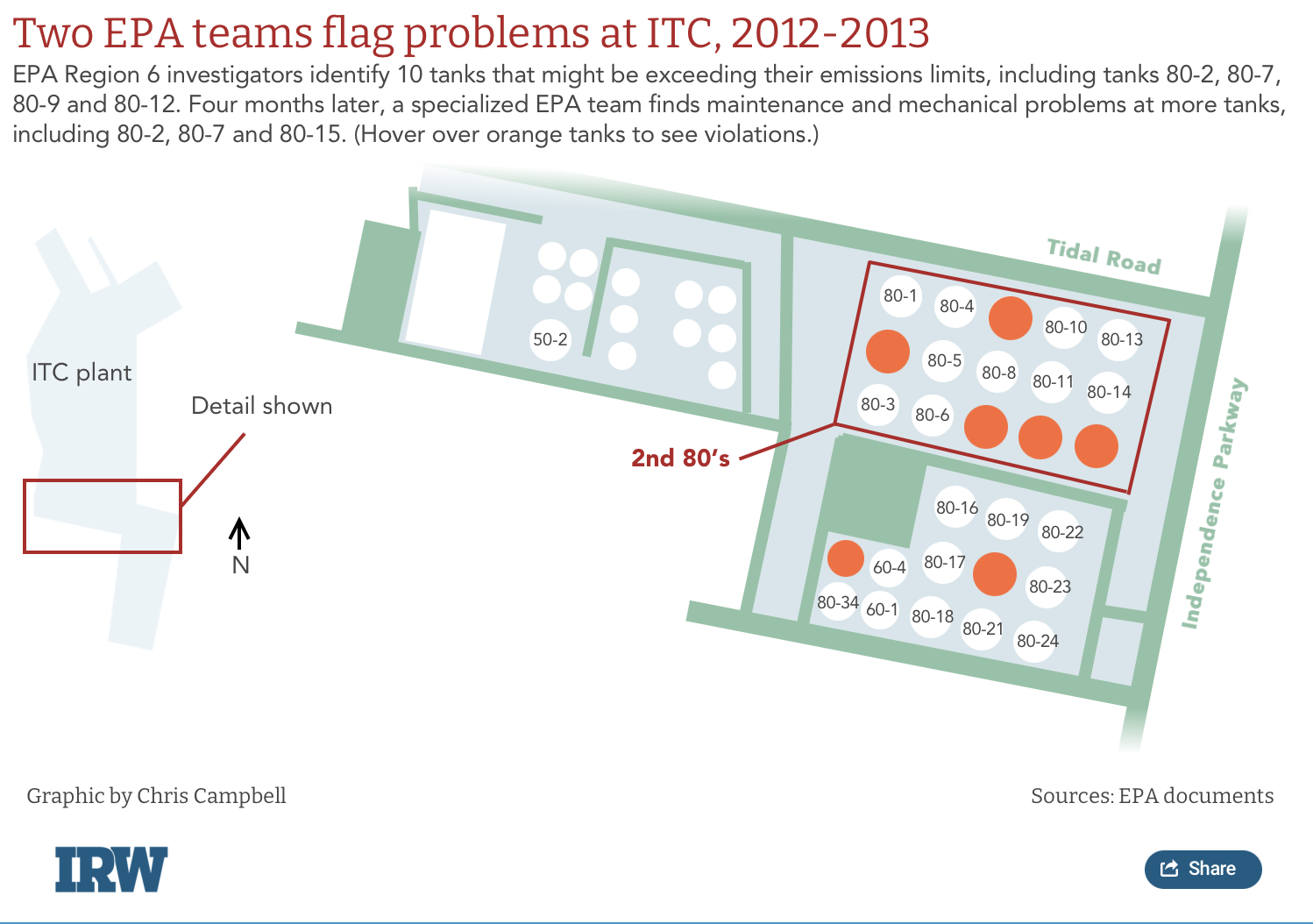

On the morning of Oct. 10, 2012, a pair of EPA investigators showed up in Deer Park for an unannounced inspection at ITC. Like Tim Doty’s TCEQ team eight years earlier, they were on the hunt for benzene. This time, they went inside the facility to get a closer look at its tanks.

The lead investigator was Dan Hoyt, an environmental engineer from Region 6 who had good reason to be worried about ITC. Data from some stationary air monitors in the area suggested there were dangerously high levels of benzene emissions in or near the facility.

Tracking emissions in large tank farms requires patience, precision, sophisticated tools and intensive training. Airborne leaks can’t be observed with the naked eye, so the investigators used heat-tracking infrared cameras to identify them. Black-and-white videos showed clouds of vapors surging through the vents that lined the tops of each tank.

Hoyt was equipped with a photoionization detector that took instant readings, but the sheer number of tanks, and the fact that they were so close together, made it difficult to pinpoint the leaks’ sources. Some of the tanks stood 120 feet tall and 40 feet in circumference, so mapping the flow of air through the complex — a critical aspect of monitoring — was challenging.

By the end of their three-day inspection, the investigators had surveyed 98 of the facility’s then-231 tanks.

Four months later — not long after ITC had applied to renew its TCEQ chemical permit for another 10 years — Hoyt sent a draft of his report to Debbie Ford, who had become Region 6’s tank expert.

Plenty of inspection reports had crossed Ford’s desk. But Hoyt’s draft stuck out. The results were “jarring,” she said, especially in the final section, labeled “Areas of Concern.”

Public Health Watch acquired a copy of the final report through a Freedom of Information Act request. It identified 10 tanks that might be exceeding their permitted limits for volatile organic compounds emissions. Four of them — 80-2, 80-7, 80-9 and 80-12 — were near Tidal Road, in the same section Tim Doty and the TCEQ team had worried about eight years earlier.

Region 6’s next step was to call in the EPA’s emissions “SWAT” team.

The National Enforcement Investigations Center, or NEIC, is a specialized branch of the EPA based in Denver. Each year it takes on dozens of the nation’s most complicated cases of industrial pollution. When a regional office needs a heightened level of expertise or seasoned investigators, it turns to the NEIC.

Ken Garing was a chemical engineer for the team. He knew the petrochemical industry inside and out. Before he joined the NEIC in 1987, he’d worked as a chemical engineer for Conoco. By the time Region 6 asked him to measure benzene emissions in eastern Harris County, he’d inspected nearly 100 plants and refineries.

In April 2013, Garing spent several days driving around the area in a custom-made van fitted with a brand-new tool: Geospatial Measurement of Air Pollution, or GMAP, technology. The $100,000 machine produced a 3D emissions map that showed real-time chemical spikes. One look made it clear to Garing that ITC had a benzene problem.

Region 6 added Garing’s findings to a draft of a formal document called a Clean Air Act Section 114 Information Collection Request. If the region wanted to move forward with enforcement, sending the 114 to ITC was a critical way to gather key details and documents.

The 13-page draft, which Public Health Watch obtained through a public-records request, laid out widespread maintenance problems and mechanical defects associated with 5 tanks, including tanks 80-2, 80-7 and 80-15. All of them were in ITC’s “2nd 80’s” that Tim Doty had flagged in 2004 and Dan Hoyt had flagged in 2012.

But Region 6’s effort to clamp down on ITC apparently stopped there.

There is no record of the 114 having been finalized or sent to ITC after the inspection, of any fines being levied or any corrective action taken.

When Public Health Watch asked why ITC wasn’t penalized after the inspection, officials at EPA headquarters in Washington, D.C., said “subsequent compliance discussions with the company and review of the evidence led Region 6 to decide against formal enforcement against ITC.”

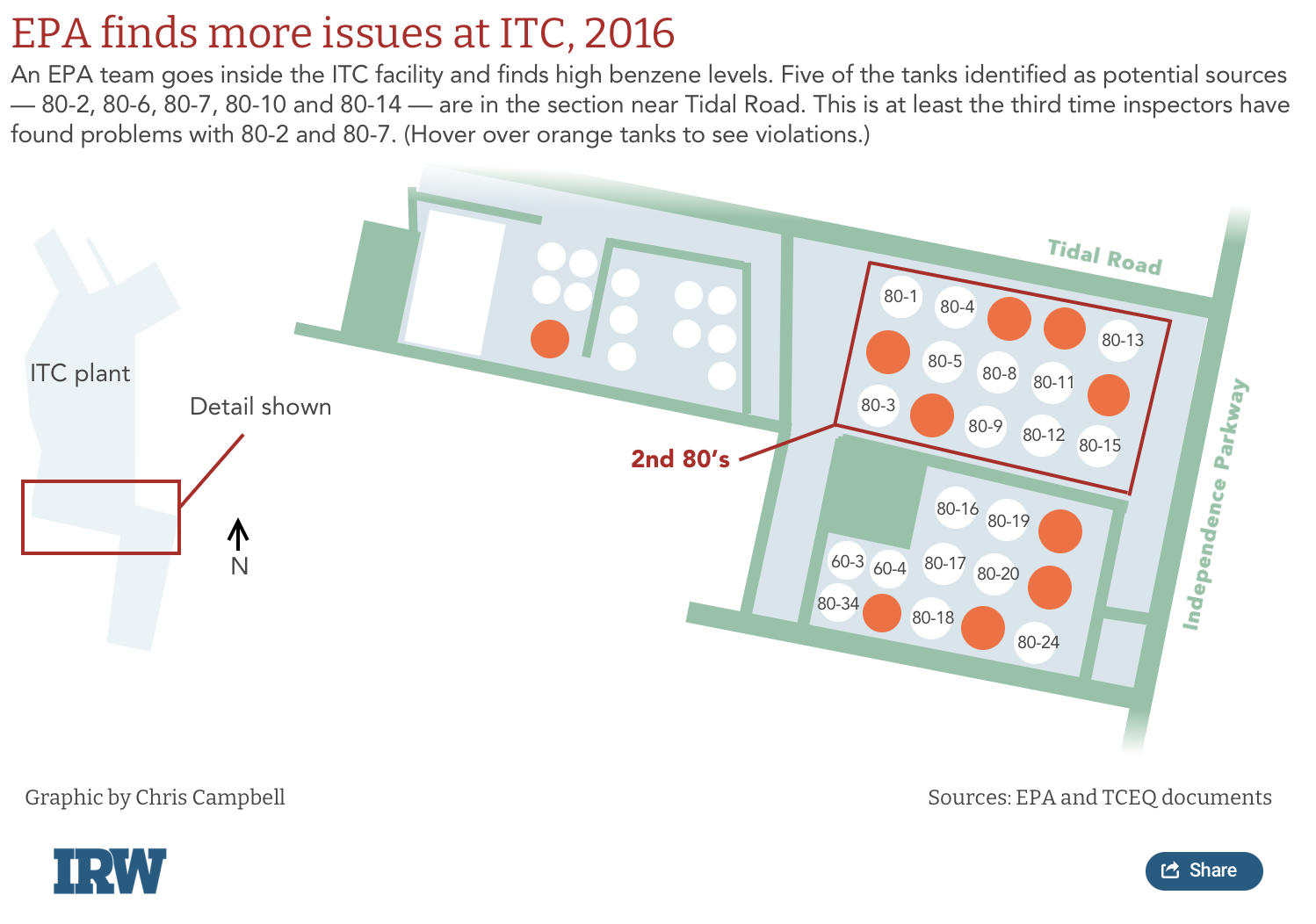

Ken Garing and the EPA’s team of specialists made a second visit to ITC on Nov. 14, 2016. This time, Region 6 asked them to conduct a full-scale inspection inside the facility, close to the tanks.

The strong odor of chemicals hung heavy in the cool Texas air that morning as Garing entered the complex. Hulking cylindrical tanks lined either side of the road like guardsmen standing at attention. Trains loaded with petrochemicals rumbled nearby.

Garing’s white Chevrolet Express was equipped with an arsenal of advanced pollution-tracking technology. Two contraptions sat atop its roof: An air monitor to track wind patterns and a 4-foot metal mast connected to a fan that sucked in atmospheric samples. It took seven car batteries just to power the potent vacuum.

After entering the mast, the air samples traveled through a Slinky-like plastic tube and into the GMAP machine, where they passed through an ultraviolet light that bounced repeatedly between two mirrors. Because specific compounds absorb light at specific wavelengths, the GMAP could identify in real time whether certain chemicals were passing through and at what concentrations. The readings went to a laptop in the front seat, giving Garing instant information about whatever he was driving through.

If emissions were low, the GMAP’s bar graph–like depictions were short and green. If emissions were high, they were bright red and stacked up like tall fences.

Garing had been using the GMAP for more than three years. But he said he’d never seen benzene levels as high as those it recorded inside ITC that day. In one part of the facility, the readings exceeded 1,000 parts per billion — more than 10 times higher than what the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health advises for workers.

“As we looked at our maps, there was all this red everywhere,” Garing said. “You usually see high emissions around one or two tanks — not around a series of tanks like we saw.

“Something wasn’t right,” he added. “It just looked very incriminating.”

Public Health Watch acquired a copy of the NEIC’s post-trip inspection report, dated April 2017, through a Freedom of Information Act request.

A large table summarizing Garing’s GMAP data showed more than 40 high benzene readings and their potential sources. Some of the emissions appeared to come from a neighboring facility. But at least half came from ITC. Five of the tanks that were flagged— 80-2, 80-6, 80-7, 80-10 and 80-14 — were in the troubled “2nd 80’s” section near Tidal Road. The highest benzene readings were found near tank 50-2 — the same tank whose 1,3-butadiene leak played a prominent role in Harris County’s first lawsuit against ITC.

The report said “it would be prudent to closely examine all available data… to decide whether further investigation would be warranted.”

NEIC delivered its findings to Region 6, which was responsible for investigating whether any of the high benzene readings exceeded ITC’s permit.

Then, just as in 2012, the effort to clamp down on ITC apparently stopped.

There is no record of Region 6 having drafted a 114 letter — a critical precursor to enforcement — or of any fines being levied or any corrective actions taken after the inspection.

Public Health Watch asked ITC if it received a 114 letter after the NEIC’s inspection. The company did not answer directly. “We responded fully to all of staff’s issues at the time,” a spokesperson said, “and ITC is not aware of any further action taken or needed.”

Public Health Watch asked to interview Region 6 leaders about why they decided not to penalize ITC after the region’s 2012 inspection, the NEIC’s 2013 benzene screening and the NEIC’s 2016 inspection. Region 6 spokesman Joe Robledo emailed the following response:

“While these inspections identified areas of concern and specifically visible hydrocarbon emission from the top of some tanks at the facility, EPA’s enforcement review of the inspection results did not identify specific noncompliance. Regarding tanks, EPA does not inspect tanks equipped with fixed roofs, internal floating roofs, or external floating roofs to achieve 100 percent emission control, so observing emissions from tanks is not necessarily a violation of a permit or federal standard.”

By August 2018, Elvia and Lalo Guevara’s oldest son had joined his parents in the petrochemical industry.

Eddie started as a contractor when he was just 18 and taking night classes at San Jacinto College. Three months later, he got a full-time job at a chemical company and dropped out of school. His starting salary was $70,000.

Mark Felix for The Texas Tribune / Public Health Watch

Like many residents of Deer Park, Eddie didn’t pay much attention to how the TCEQ did — or didn’t — regulate the facilities that helped his community thrive. ITC’s persistent maintenance problems and environmental issues rarely made news. Since 2002, it had been penalized only $270,728 by the TCEQ, EPA and Harris County combined. That was barely a blip on the balance sheet for ITC’s owner, the Mitsui Group, which recorded $7.2 billion in profits in 2018 alone.

On the evening of Saturday, March 16, 2019, a chain of events began in ITC’s “2nd 80’s” that would draw national attention to the facility’s emissions problems. Reports from the Harris County Fire Marshal’s Office and the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board laid out what happened.

About 7:30 p.m., operators began unloading two truckloads of butane into tank 80-8, according to the safety board’s preliminary report. The highly flammable liquid was being added to naphtha, an ingredient used in gasoline, to increase the fuel’s octane level. After the trucks were emptied, an external pump was left running to continue mixing the product.

The next morning, the pressure inside tank 80-8 suddenly dropped, a sign of a possible leak. About 9:30 a.m., more than 9,000 gallons of the naphtha-butane mixture began spilling onto the ground. The safety board report said the tank farm didn’t have a fixed gas detection system, which would have set off alarms to warn employees of the emergency.

The fire marshal’s office described what happened about a half-hour later, when an ITC supervisor was testing a tank. He heard the groans of metal grinding in the distance, but assumed it was two rail cars coupling together.

Moments later, he saw flames shooting up a tank about two football fields away. He wasn’t sure which tank it was, but he saw that it was at the heart of the “2nd 80’s” — the section whose high emissions had worried TCEQ and EPA inspectors for at least 15 years.

The fire marshal’s report said the tank farm didn’t have an automatic fire alarm system, so the supervisor grabbed his handheld radio and alerted the facility’s emergency response team. Then he ran to the nearby security office and activated the fire alarm.

According to the safety board, tank 80-8’s valves couldn’t be closed remotely. To turn them off, someone would have had to charge directly into the fire.

The tank farm also didn’t have an automatic sprinkler system, the fire marshal’s report said. The facility’s on-call fire team was still minutes away, so the ITC supervisor sprinted toward the nearest firefighting station. As he got closer, he saw that tank 80-8 was at the center of the inferno.

Courtesy of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

By the time he reached a company firefighting station, the flames had crawled from the 120-foot tank’s base to its roof.

The operator who was responsible for the “2nd 80’s” that day was already there in full protective firefighting gear. He and the supervisor didn’t have a direct shot at the fire, so they tried to bounce water off another tank and onto 80-8.

But the water pressure was too weak to reach the flames.

As the operator screamed into his radio for more water pressure, he saw a second tank — 80-11 — catch fire.

A gas-fueled fireball rose more than 150 feet into the air. Ash rained down on emergency responders as they fought to slow its spread. Billows of thick, black smoke formed an enormous plume that could be seen for miles.

Eddie Guevara, who was working a few miles from ITC that Sunday, watched it drift toward his family’s home. He called his father and brother to warn them, but he kept on working. He had learned to live with the hazards of his job.

Debbie Ford, the Region 6 tank specialist, was inspecting tanks in Louisiana that day. When she got back to the office, she said the region’s leaders were huddled in closed-door meetings. She wasn’t included — so she began researching the fire on her own.

“It’s always a shock when there is an explosion or fire at a facility you have inspected or have knowledge of,” she said. “The question is whether management tried to deflect any responsibility for not following up” on its past inspections.

“Only those folks who were in the room would know,” she said.

Texas Tribune reporters Alejandra Martinez and Erin Douglas contributed to this story. The Investigative Reporting Workshop provided editing and graphics support. The project is co-published with Grist.

Reporters: David Leffler and Savanna Strott, Public Health Watch

Copy editing: Merrill Perlman

Photography: Mark Felix, Emil T. Lippe and Liz Moskowitz

Photo editing: Pu Ying Huang

Editors: Susan White, Dave Harmon, Jim Morris

Graphics: Chris Campbell

Data analysis: Caroline Covington, Jade Khatib, José Luis Martínez

Web design: David Fritze