This story is part of the Grist series Flood. Retreat. Repeat, an exploration of how communities are changing before, during, and after managed retreat.

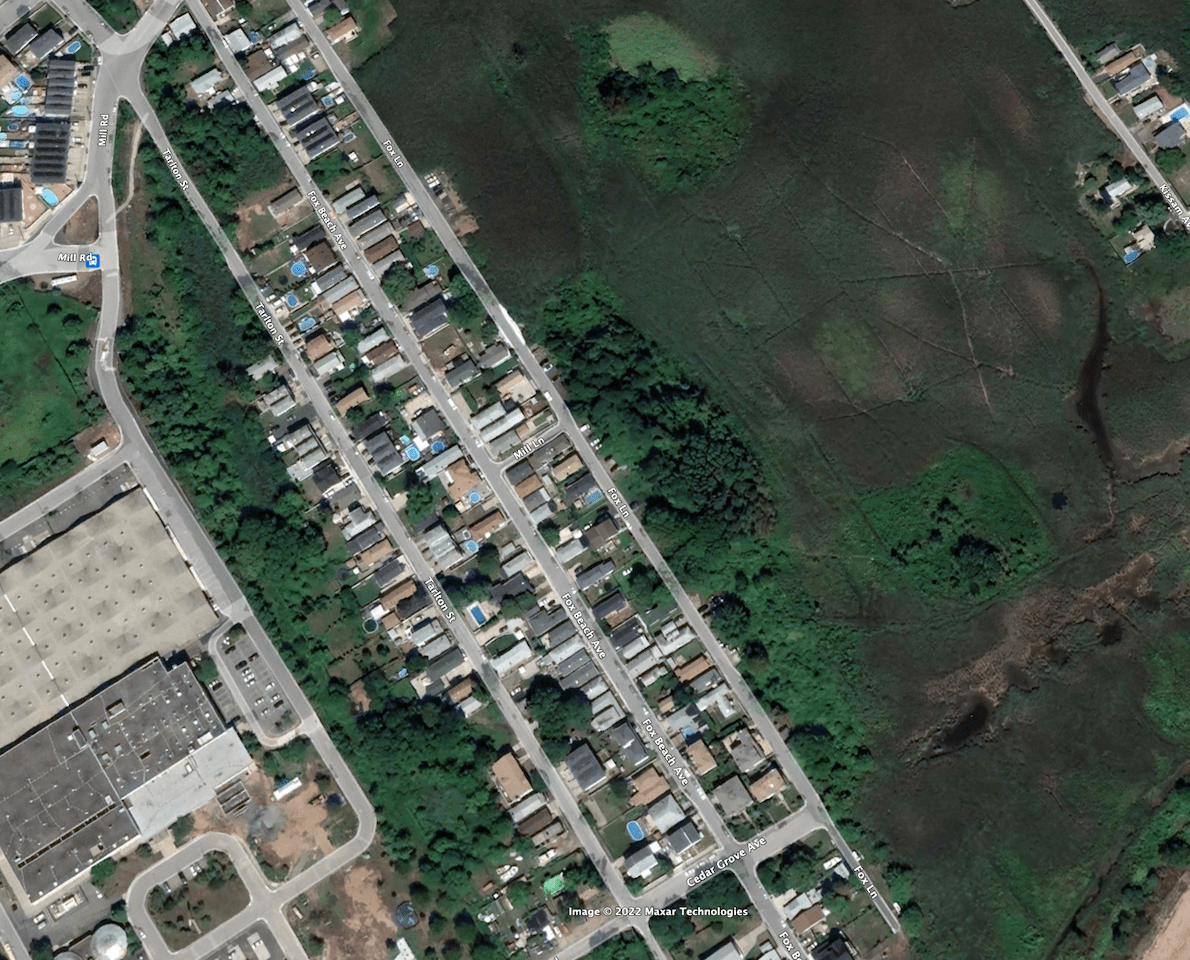

Less than an hour’s drive from downtown Manhattan, on the eastern shore of Staten Island, lies the neighborhood of Oakwood Beach. A decade ago, it was a tight-knit working-class community of roughly 300 homes. Bungalows and beach houses lined its quiet streets, boasting ample backyards, easy water access, and a calmness rare in a city like New York. Today, the neighborhood is unrecognizable, a barren landscape of empty lots and flooded streets. Almost everyone has left.

When Superstorm Sandy ravaged New York on October 29, 2012, Oakwood Beach was one of the hardest hit areas. A 14-foot storm surge, among the highest recorded in the city, swept across the neighborhood. Entire houses were lifted from their foundations and carried across the surrounding marsh. Three people died.

Low-lying and encircled by wetlands, Oakwood Beach had always been prone to flooding, but the devastation caused by Sandy was unprecedented. Rather than rebuilding and waiting for the next storm, residents decided they would be better off elsewhere.

Andrew Burton / Getty Images

In the months that followed, they successfully lobbied the government to buy out their homes. The state of New York, using federal grants from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, agreed to pay pre-storm prices for the destroyed properties, demolish them, and never redevelop the land. Residents would be out of harm’s way in the event of another disaster and armed with money to resettle elsewhere. In time, nature would retake the area, creating a natural barrier against future storms. The strategy, called managed retreat, is what some experts say is the only long-term solution for waterfront areas like Oakwood Beach in the face of extreme weather and sea-level rise.

Buyouts in the neighborhood started in 2013, the first in a series of post-Sandy retreat programs on the eastern shore of Staten Island. The vast majority of residents chose to participate, but a few did not. Some simply didn’t want to leave their longtime homes. Others felt they couldn’t afford to relocate in New York’s expensive housing market for what the state was offering.

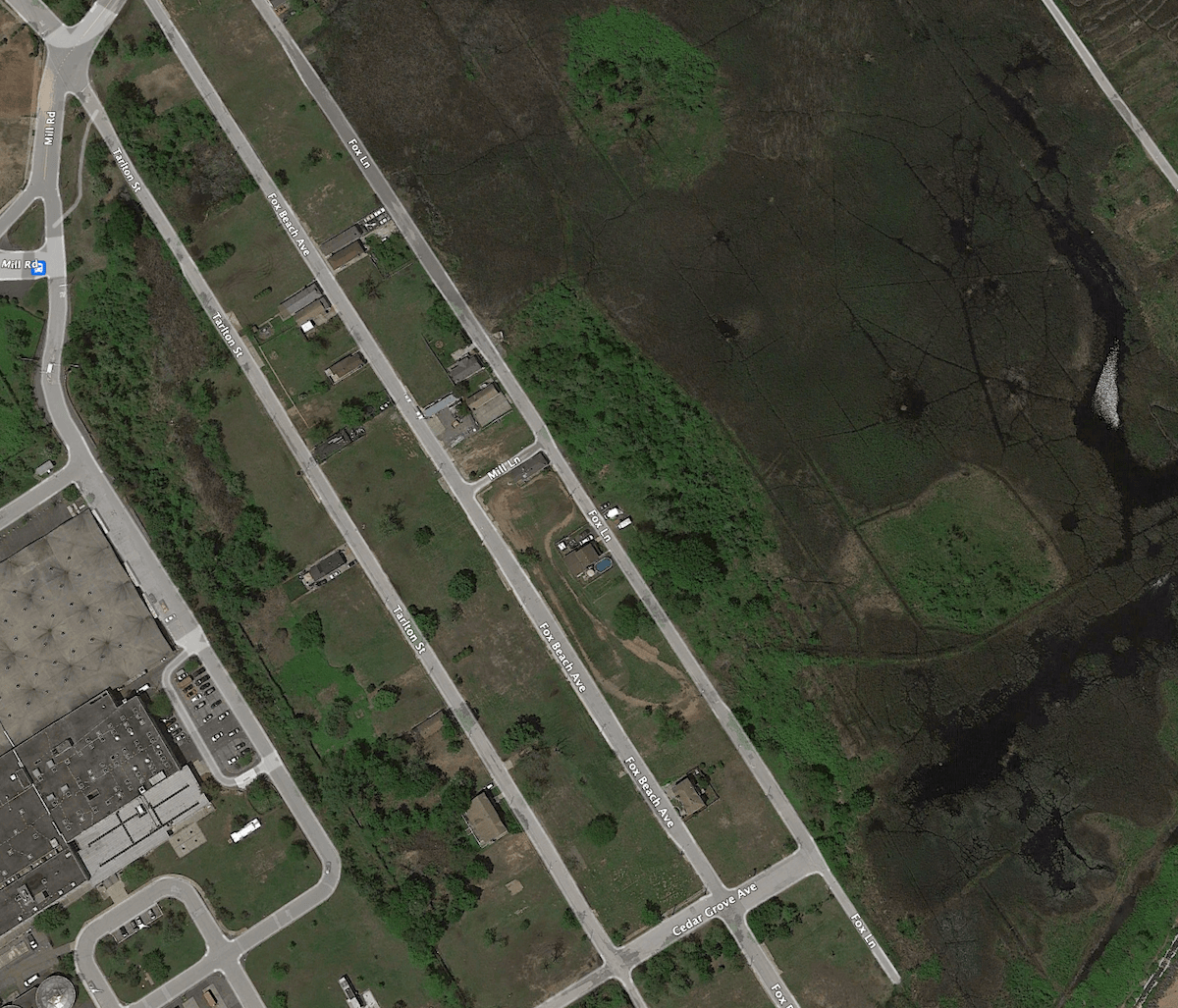

Today, a decade after Sandy, these holdouts reside in a neighborhood that is by design becoming more wild. The state acquired 308 properties during the buyouts and almost all of them have been demolished. Tall stands of vegetation from the surrounding marshland encroach into empty lots. Foxes, opossums, and snapping turtles have moved in. Deer and geese now outnumber the residents. Just 18 active households remain in the buyout zone.

The holdouts say they have been forgotten by the city. Streets are poorly maintained and basic services like trash collection are unreliable. The area is a frequent dumping site for people in the surrounding neighborhoods; old furniture, vehicle parts, and trash are strewn across some of the empty lots where homes once stood. Flooding is now a constant problem. Calling 311, the city’s line for non-emergency grievances, is a way of life in Oakwood Beach, but it yields few results.

“I pay my taxes,” said Christopher Camuso, 51, a resident who contacts city agencies about road conditions and flooding on a regular basis. Like his neighbors, he never imagined Oakwood Beach would become so neglected when he decided not to move. Residents were never told during the buyout process that as the area became less densely populated, it would be deprioritized by the city’s basic service providers. (City officials and the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery contend they haven’t neglected the area.)

Andrew Burton / Getty Images

Chris Camuso, left, stands in front of his Oakwood Beach house in September 2022. Camuso says the neighborhood has been deprioritized after many of his neighbors took buyouts. Eight years earlier, right, volunteers helped him rebuild his house so he could move back in after Superstorm Sandy. Grist / Joaquim Salles, Andrew Burton / Getty Images

It’s an issue that municipalities across the country may soon face as more governments turn to buyouts as a solution to a changing climate. The overwhelming majority of buyout programs are voluntary, and it is extremely rare for every individual in a community to relocate. Those left behind are finding themselves in an even more vulnerable position than they were before.

Lois Kelly, 71, has lived in Oakwood Beach since 1985. “It was a lovely neighborhood, like a little community,” she said. When Sandy hit, she and her husband were trapped in their one-story house as it filled with water. They got enough money from the insurance company to rebuild and chose not to relocate. Oakwood was their home, and they didn’t feel like starting over.

A decade later, just a few feet from Kelly’s doorstep, a large section of the street is flooded most of the year. Ducks and geese swim about as if on a lake. Residents say the street, Fox Lane, has been gradually sinking over the past decade. Cars cannot drive down it from end to end. The few that do often become stuck, including city vehicles like sanitation trucks. To leave her house, Kelly has to take a circuitous route through one of the parallel streets to avoid the water. The dry sections are cracked, uneven, and filled with large potholes.

Grist / Joaquim Salles

“When you walk here, one minute you’re on something, the next minute you’re not,” she said. One morning in 2019, she was sweeping the street in front of her house when she tripped on uneven ground and fell face-first, sustaining a broken rib and a brain stem injury that affected her balance. She sued the city for negligence. The city argued Kelly was culpable in the accident and should have been aware of the risks, according to court records. The case was eventually settled for what Kelly deems “a low amount.” She has since taken to paying a contractor to fill the potholes in front of her house with packed gravel, a temporary low-cost solution. Still, she doesn’t want to move out. “Living here in the quiet is a beautiful thing,” she said.

Grist contacted the city’s Department of Transportation about road conditions in Oakwood Beach and was referred to the state, which still owns many of the lots in the neighborhood (the others have been transferred to the city and to the Staten Island Youth Soccer League). Paul Onyx Lozito, deputy executive director for Housing, Buyout, and Acquisition programs at the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery, said in a statement that road and water infrastructure maintenance would be under the jurisdiction of New York City agencies.

On the opposite side of Fox Lane, only two houses remain. Camuso is among the holdouts who still had years left on their mortgages when Sandy struck. The state offered $239,000 for his house — the pre-storm value — but he chose not to take the offer. Nearly all of that money would have gone to the bank that owns his mortgage, he said, leaving almost nothing for a down payment on another home.

Before Sandy, Oakwood Beach was one of the more affordable neighborhoods in the borough, which made it hard to find comparable housing elsewhere when the state offered buyouts. That challenge has only gotten worse. The median sale price for a home in Staten Island was $417,000 in 2013. Today, that figure has increased to $685,000. “If I walk away from this, where am I going to go?” Camuso said. “I have no money.”

Camuso works for the city’s Department of Sanitation and says there were periods in which he had to take his own trash to work because the garbage truck often skipped his part of the neighborhood. His next-door neighbor, Joe Varo, says there have been three-week stretches when his garbage was not been collected.

In a statement to Grist, the Sanitation Department’s press secretary said crews “take seriously our mission to keep New York City streets clean, safe and healthy, and that includes every public street across the five boroughs.” She recommended residents call 311. “We will respond,” she said.

Anthony DeFrancisco and his family are the only residents left on Tarlton Street. “You ever watch those scary movies where the guy is all the way out in the woods by himself and the murderer says, ‘No one is ever going to hear you scream’?” he said. “It’s kind of like that here.”

DeFrancisco lives in a small house with his mother, sister, and four nephews. It’s raised a few feet above ground, yet it still filled with water chest-high on the night Sandy hit. Everything in it from appliances to family photos was lost, and the house had to be gutted.

Afterward, the family got insurance money to fix some of the damage. DeFrancisco was eager to relocate when the buyouts became a real possibility, even though he still had decades left on his mortgage. But the state’s offer deducted any insurance payments that were not accounted for, and in the wake of the storm, DeFrancisco had not kept receipts of how he had spent the insurance money. For years after Sandy he searched the city for an affordable mortgage that would accommodate his large household, without success.

Since Sandy, his problems with flooding have gotten exponentially worse. Before the storm, he says, his basement would flood once every couple of years. Now, he estimates it floods 10 times a year. As with all remaining residents on Oakwood Beach, rain forecasts are a constant source of anxiety.

“Every time they say thunderstorms, tornados, I get nervous because you never know,” said Connie Martinez, who lives on the street parallel to DeFrancisco’s. “I have everything prepared where I can grab and run.” Martinez moved to Oakwood Beach in 1973 when her eldest daughter was just a year old. She would go on to raise three children in the neighborhood. “I could stick my head out the window and see where they were, and I didn’t have to worry about them. It was perfect.”

Grist / Joaquim Salles

Even though she loved Oakwood Beach, Martinez wanted to leave after Sandy. But her husband, who was an avid gardener, didn’t agree. Where else in New York City would he find space for tomato vines and peach trees? They rejected the state’s offer of $489,000 for their house.

Martinez’s husband died this past January, and she is ready to move on. The neighborhood has changed. “It’s lonesome,” she said. “I don’t go outside hardly anymore because I don’t like looking at the empty spaces where the houses were, where the people I knew were.” The government-run buyout program has officially ended, but she was recently able to sell the house on the private market for roughly the same amount she was offered in 2013.

“It’s time for me to start someplace fresh,” she said. She hopes to be settled in a new house by the end of the year, but the search has been difficult. The money doesn’t go as far as it did a decade ago, and Martinez is struggling to find a comparable home on Staten Island that suits her needs.

Unlike Martinez, most remaining residents of Oakwood Beach have no plans to leave. Some have learned to enjoy the isolation. If Oakwood Beach was a tranquil place before Sandy, now it’s akin to living in the countryside. The long-term prospects for the area, however, are dire. With worst-case scenario sea-level rise, the community could be permanently flooded in just over 30 years, according to the latest projections by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

A long-delayed project to build a seawall along the eastern shore of Staten Island might buy the neighborhood a few more years beyond that, but it won’t protect it entirely. Climate scientists predict that the likelihood of Sandy-level storms will vastly increase. By 2100, major storm surges that used to occur in New York only once every 500 years may strike the city every 25 years.

Predictions like these are what make managed retreat a favored adaptation strategy by many climate resilience experts. “Long-term risk is gone. People are no longer in harm’s way of floodwaters,” said Michael McCann, an adaptation specialist at The Nature Conservancy*, which has worked with the federal government to return bought-out lots in Staten Island to nature. “With pretty much all other measures of flood adaptation, there’s going to be some residual risk if that structure were to fail.”

The latest New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan, a document put out by the city in 2021 that outlines a 10-year vision for the waterfront, recognizes that “climate change and sea-level rise will make some areas unsuitable for residential use,” and alludes to managed retreat with terms like “housing mobility” and “land adaptation.”

Which areas of New York City might be eligible for managed retreat programs in the future is anyone’s guess, but a growing body of research shows that adaptation strategies are applied differently depending on socioeconomic factors. Low-income neighborhoods are more likely to be bought out, and with that comes a loss of community. Neighborhoods where property values are high are more likely to receive coastal armoring and beach nourishment — even if those coastal armoring projects will be obsolete by the end of the century because of rising seas. And then there’s the issue of what happens to a bought-out neighborhood where a few residents are still holding on.

“I don’t even think there’s that many precedents about what is the ethical and legal obligation for a municipality to continue to provide services, roads, sewer, electrical as communities are in transition,” said McCann. “It’s a dilemma that I think more and more municipalities are going to have to face.”

For the few remaining residents of Oakwood Beach, it’s a predicament they are already facing.

*Editor’s note: The Nature Conservancy is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers play no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.