From the Winter 2025 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The word came in a cellphone text from finch researcher Matt Young, who was scouting along a forest road in northern Minnesota’s Sax-Zim Bog: “Grosbeaks coming in!”

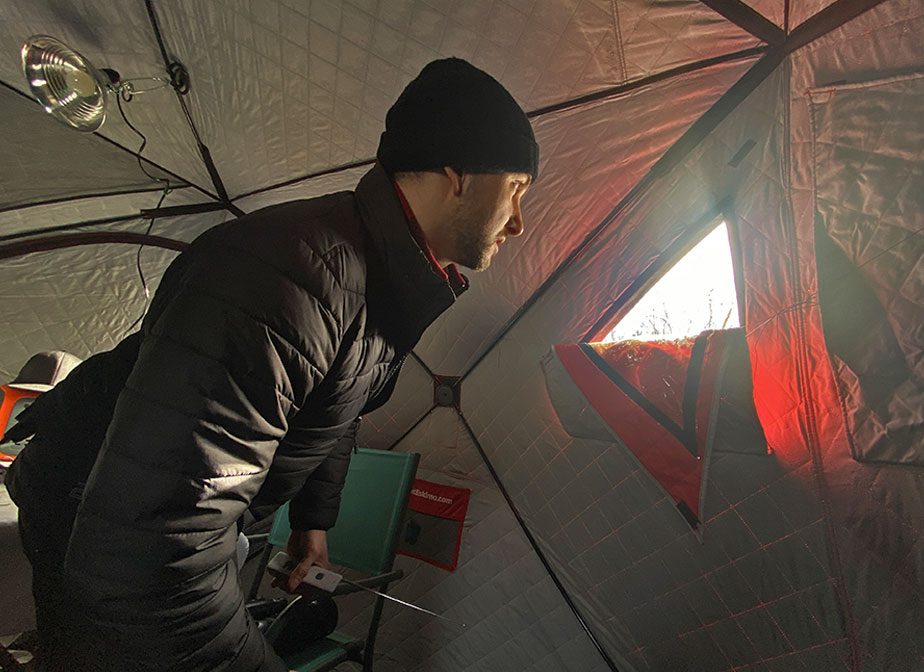

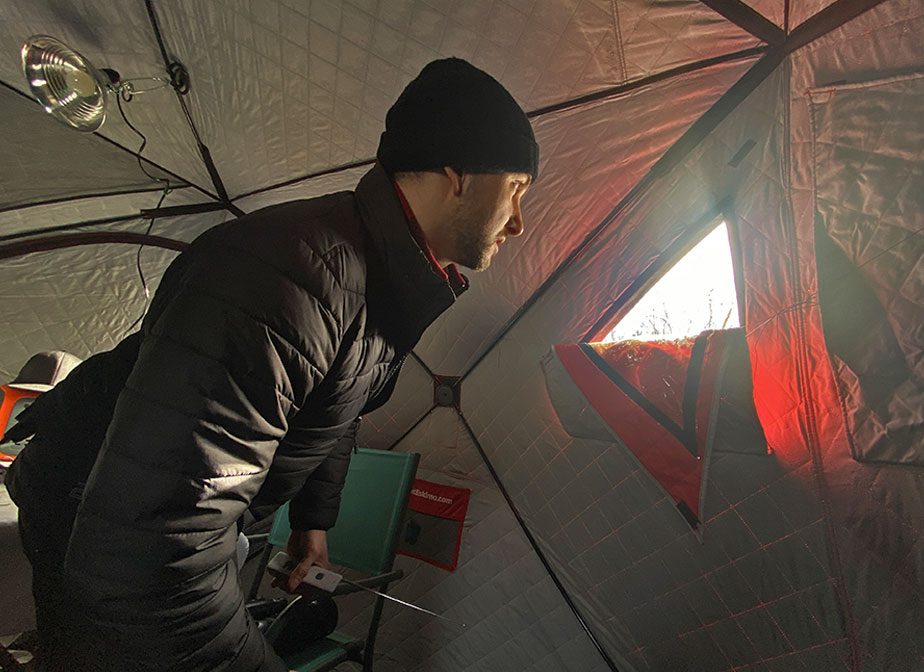

About a quarter-mile away scientist David Yeany was sitting in a makeshift blind, which was really an insulated ice-fishing pop-up shelter—perfect for staying warm in a frozen bog where winter temps can kiss minus 40. He was stationed at the platform seed feeders just outside the Sax-Zim Bog Welcome Center, a favorite foraging haunt of winter finches this time of year that draws clouds of Redpolls, siskins, crossbills…and Evening Grosbeaks.

It’s not so easy to find Evening Grosbeaks anymore across the United States. According to Breeding Bird Survey data, the North American grosbeak population has plummeted by about 75% since 1966. That’s why the scientists were conducting this field research last February—to uncover the exact locales grosbeaks use in their migratory journeys, and figure out what threats are causing their declines.

Yeany watched from the ice-fishing hut, eyes peeled for flashes of jet black and dandelion yellow swooping in to a pile of shiny black-oil sunflower seeds glistening against the white snow. Inches away, a bow-net trap was set, and when the flock of grosbeaks that Young had spied swept down to the seeds, Yeany fired a remote trigger. Moments later he and a field assistant were delicately fishing six grosbeaks out of the netting, and subjects #396 to #401 were added to the study—each one weighed, measured for wing length, analyzed for healthy fat deposits beneath its feathers, and outfitted with a USGS metal ID leg band. If it was heavy enough to carry a transmitter, the grosbeak was equipped with a satellite-tracking tag.

This research is one of four pilot projects of the Road to Recovery initiative, also called R2R—a scientists-led effort to reimagine bird conservation in the wake of the startling study published in the journal Science that showed North American breeding bird populations have collectively lost 3 billion birds in the last 50 years. Five years after that landmark study made headlines around the world, the R2R effort aims to shake up the way government agencies and academic institutions have traditionally gone about trying to save birds. The new approach uses private funding and knowledge sharing to power up innovative field research with promising conservation potential, like the Evening Grosbeak study.

“That’s exactly where Road to Recovery wants to step in and enable and support,” says Pete Marra, a leader of R2R and a Georgetown University professor of biology, who was a lead author on the 3 billion birds lost research. “The people out in the field are doing the tough work on the ground. Our goal is to turn that information into gold, as far as conservation goes.”

Quebecois Grosbeaks Visit a Pennsylvania Backyard

David Yeany started his research at his boyhood home in Forest County, Pennsylvania, on the southeastern edge of the Allegheny National Forest. In years past Yeany had built a platform bird feeder with his dad that hosted Evening Grosbeaks during a midwinter irruption. In 2017 Yeany returned as an avian ecologist with the nonprofit Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, launching a collaboration with the Carnegie Mellon Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Avian Research Center to capture and put radio-tracking tags on a few grosbeaks in winter and see where they went come spring.

It was the first-ever tracking study on the migration ecology of Evening Grosbeaks, and it yielded immediate discoveries. It turned out the tracks on these overwintering grosbeaks in western Pennsylvania led to breeding grounds in Quebec. What’s more, over the course of a few years Yeany learned that his dad’s backyard bird feeder was getting different grosbeaks from winter to winter. It wasn’t always the same birds showing up at a particular overwintering site; instead they were ranging over a wide area. But they stayed south for a significant chunk of the year, with some grosbeaks relying on food resources in the Pennsylvania landscape for up to six months.

“[That finding] significantly shifted our view to see an increased responsibility for conserving this steeply declining bird,” says Yeany.

Around 2020 Yeany’s project attracted the attention of Matt Young, who had just founded the Finch Research Network, or FiRN—a global effort to facilitate information-sharing among scientists studying any of the more than 230 species of finches worldwide. FiRN contributed some funding to Yeany’s project to buy more radio tags, and Young offered a helping hand in the field. But still, the scope of the grosbeak research was limited to putting tags on grosbeaks in Pennsylvania, and the radio tags only recorded a data point whenever a grosbeak flew by a radio tower with a receiver that could read the tag—which meant data collection was intermittent.

“It was all just kind of cobbled together,” says Young.

Then in October 2021, Pete Marra took notice of this scrappy grosbeak research startup. And Marra has a soft spot for Evening Grosbeaks.

“They’re just disappearing before our very eyes,” Marra says. He has fond memories of watching big flocks of grosbeaks in winter as a kid growing up in Connecticut in the 1970s. But now, he says, “you just don’t see them anymore.”

Marra brought the backing of R2R to the grosbeak research, with an aim to upgrade the technology and greatly expand the scope of the project. Now Yeany and Young are studying five different populations of overwintering Evening Grosbeaks across North America, from the upper Northeast and lower Northeast to the Upper Midwest, the Intermountain West, and the Pacific Northwest. And they are deploying top-of-the-line satellite tags that can relay a nearly real-time data stream from wherever the birds go.

The dream, says Yeany, is to build a master “framework for migratory connectivity” among North America’s Evening Grosbeaks—to fully understand how these different subpopulations move across the continent, and importantly, where and why these populations are hemorrhaging grosbeaks.

The batches of data from satellite tags deployed in Minnesota have yielded some surprising insights. Yeany says that overwintering grosbeaks tagged at Sax-Zim have traveled “in all directions” on spring migration. Three grosbeaks went north into Ontario, one flew west to Manitoba, and one embarked east on an overwater flight across a Great Lake.

Yeany says the sojourning grosbeak was likely on the Minnesota side of Lake Superior at sunrise on May 15, 2023. By 11 a.m., it was already on the other side of the lake, about 140 miles east of Superior’s eastern shore. It kept going and eventually settled into a forest in Quebec for the breeding season.

The most shocking finding, though, was that about three-quarters of the satellite-tagged grosbeaks stayed local year-round, disappearing into the boreal-like forests around Sax-Zim.

“We have evidence that the birds are staying there, they’re just not detectable,” Yeany says.

“They’re known to be super secretive breeders, believe it or not,” says Young, despite how conspicuous grosbeaks can be at backyard bird feeders in winter.

A recurring theme among many of the grosbeaks tagged at overwintering areas in Maine, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania is a migratory connection to areas of spruce budworm outbreak in the boreal forest. Even though they are famous for feasting on sunflower seeds in winter, many Evening Grosbeak populations key in on sources of spruce budworm larvae for the vital protein needed to lay eggs and rear young.

Another general trend among grosbeaks was illuminated by the plight of #228, a bird Yeany tagged in the winter of 2022 in Maine. By summer #228 was almost 250 miles to the northeast, spending the summertime in a spruce forest in far eastern Quebec. The following winter, #228 was recorded almost 1,000 miles back to the west along the shore of Lake Huron, where he met his demise—a victim of a window collision at a home with a backyard bird feeder.

According to biologist Stephanie Egger at the U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Laboratory, Evening Grosbeak is the most reported species among reports of banded birds that died from flying into windows. Young says grosbeaks “seem to be susceptible to window kills, because they’re social and they flock at feeders”—which means they are often attracted to backyards near residential structures, which puts them flying near ground level among deadly glassy mirages.

For Marra, insights from the Evening Grosbeak migratory-connectivity research about ties to spruce budworm areas and threats from window mortality are exactly the research outputs that the R2R initiative values—and that will be needed to turn around bird declines.

“Nature’s resilient,” he says, explaining that once the drivers of decline for a species are turned off, bird populations have an incredible capacity to heal on their own. “The whole thing is, how do you identify the smoking guns?”

Founding a Road to Recovery

On September 20, 2019, the New York Times ran a front-page story with the headline: “An Ecological ‘Crisis’ as 2.9 Billion Birds Vanish” [published online with the title Birds Are Vanishing From North America]. Hundreds of other newspapers, TV news outlets, and news websites echoed the alarm bells about the study published in the journal Science.

“It was sort of a shot heard around the world,” Marra says. But he also says that he knew his work wasn’t done. “You don’t publish a paper like this and just go back to your day job.”

Marra says he had hoped the research would spark an effective government response, similar to the banning of DDT after revelations in the book Silent Spring. But five years later, Marra says he feels policy in the wake of the 3 billion birds lost study has been lackluster. So he decided to join up with other scientists to create their own response.

One of his partners in forming R2R was Ken Rosenberg, a retired Cornell Lab of Ornithology conservation scientist who was also a coauthor on the Science research. Rosenberg describes the R2R model as a philosophical shift in the way bird conservation is conducted; instead of conserving habitat for a suite of several bird species in a landscape, it’s a more surgical approach.

“Protecting habitat is important,” he stresses. “It could be that we would have lost 10 billion birds, if we weren’t doing all those things.

“But there’s a set of birds that’s slipping through the cracks, because we’re not really addressing the actual causes of their declines.”

Rosenberg is talking about the Tipping Point species, a set of steeply declining birds identified in the 2022 State of the Birds report that are not yet protected as endangered, but in real danger—having lost more than 50% of their populations in the past 50 years.

Rosenberg and Marra helped launch R2R in 2020 as an independent consortium of scientists across several government, academic, and nonprofit groups who wanted to advance a focused approach to turning around declines for Tipping Point birds. Over the past four years, R2R has convened hundreds of scientists and conservationists in more than 20 workshops and webinars to set strategies, share best practices and information, and encourage the mobilization of research toward conservation action.

“We call it a movement and not an organization, because we don’t want to create a structure that competes with other structures,” says Rosenberg about R2R. “We’re trying to be this catalyst for change and conservation.” And importantly, he says, “we were successful in getting new private funding.”

Marra was able to secure support from the Knobloch Family Foundation for R2R to use seed money for investing into four working groups of scientists that were doing conservation research on Tipping Point birds. Each R2R pilot project received $100,000. In addition to Yeany’s Evening Grosbeak research, the initiative selected working groups focused on Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Golden-winged Warbler, and Lesser Yellowlegs.

Addressing the Plight of Lesser Yellowlegs in the Caribbean and Beyond

The investment in the Lesser Yellowlegs working group is already yielding the kinds of results that R2R prizes. Prior research that started in 2018—conducted by scientists at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, University of Alaska Anchorage, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Environment and Climate Change Canada federal agency—put tracking tags on yellowlegs across their breeding range and identified which migratory populations were most vulnerable to harvest in the Caribbean and northern South America—where shorebird hunting is a longstanding tradition. Other research had showed that tens of thousands of yellowlegs were being killed on migration through the Caribbean every year. But at that point, as with the early days of Yeany’s grosbeak study, the research and capacity for follow-up actions were limited.

“Then the Knobloch foundation came along,” says Katie Christie, an avian biologist at ADF&G who helps lead the yellowlegs working group. “We were really fortunate to be chosen as an R2R pilot species and to receive funding from them, because that really accelerated our progress in terms of research and conservation, and allowed us to expand and investigate new questions regarding limiting factors for Lesser Yellowlegs.”

Today the Lesser Yellowlegs Working Group includes 24 scientists from Alaska and Canada all the way down to Colombia and Argentina. In the Prairie Pothole Region of the Dakotas and Montana, Knobloch foundation funding is underwriting research on the impacts of neonicotinoid pesticides exposure to yellowlegs and other shorebirds during migratory stopovers. So far the highest levels of neonic loads in blood samples have come from Lesser Yellowlegs, Semipalmated Sandpipers (another Tipping Point species), and Killdeer (also a shorebird in decline).

R2R also helped shut down a threat to yellowlegs. Brad Andres, a longtime USFWS shorebird scientist who is now retired, says that R2R helped facilitate a study by a USGS biometrician that clearly demonstrated the unsustainable levels of killing at migratory stopovers in the Caribbean were contributing to Lesser Yellowlegs population declines. Andres says the study convinced officials for the French departments of Guadeloupe and Martinique to completely ban yellowlegs hunting there.

Andres, who has worked in shorebird conservation for almost 40 years, says his work through R2R is reinvigorating.

“I tried to push before I left Fish and Wildlife … we made some attempts like the focal species program. It never really caught on, though,” he says. “We’re finally doing something with those lists that we’ve been generating my whole career.”

Despite some early wins, Marra cautions that R2R has a long way to go—and will require more funding. Migratory connectivity research is expensive. For example, the Evening Grosbeak study has deployed 66 satellite-tracking tags at a cost of $2,000 each, plus an additional $800 per tag, per year, for data fees.

A scaling up beyond the four R2R pilot working groups means a scaling up of investment, Marra says.

“We’re talking about 112 Tipping Point species. Each species is going to cost more than a million dollars easily,” he says. “It’s not a cheap undertaking, that’s for sure. But we got ourselves in this mess.”

Engaging People to Become Part of the Solution

Even as David Yeany is organizing more fieldwork out West for tagging Evening Grosbeaks and adding to the project’s body of migratory connectivity research, he is envisioning how the study can spark a grosbeak turnaround. He says one possibility is collaborating with forestry agencies in spruce budworm outbreak zones, to limit the spraying of pesticides and impacts to breeding grosbeaks. Young has already been using the grosbeak research to give public talks about the importance of making windows bird-safe.

“There’s a lot of bird feeders, and there’s an opportunity for a lot of outreach related to reducing window collisions,” Yeany says. “I think the collision issue is a low-hanging fruit.”

This kind of public outreach that effectively engages people in conservation, called social science, has become a key part of the R2R equation, Marra says: “You’ve got to bring along the human beings who are part of the problem, so they become part of the solution.”

R2R is also recruiting younger scientists, says Rosenberg: “passing the torch to a new generation of conservationists.” A new R2R subcommittee called Future Leaders in Conservation is led by Quinn Carvey, a PhD student who studies Atlantic Puffins at the University of New Brunswick in Canada.

“It’s this whole new movement within the movement. It’s all about the future,” says Rosenberg. “I think it’s one of the most exciting things in R2R.”

Part of broadening the membership in Road to Recovery is about sharing the responsibility, and igniting a sense of ownership among scientists who work in bird conservation to mount an effective response to 3 billion birds lost.

“If it’s not us, who is it?” asks Marra. “We’re still seeing massive bird declines. … This is the process of extinction. And if we walk away, we would be guilty.

“So we’re trying to figure it out. What works, and what doesn’t. I don’t think we have all the answers,” he says. “But we’ve got a team of people, and we’re trying.

“I feel like people are inspired.”