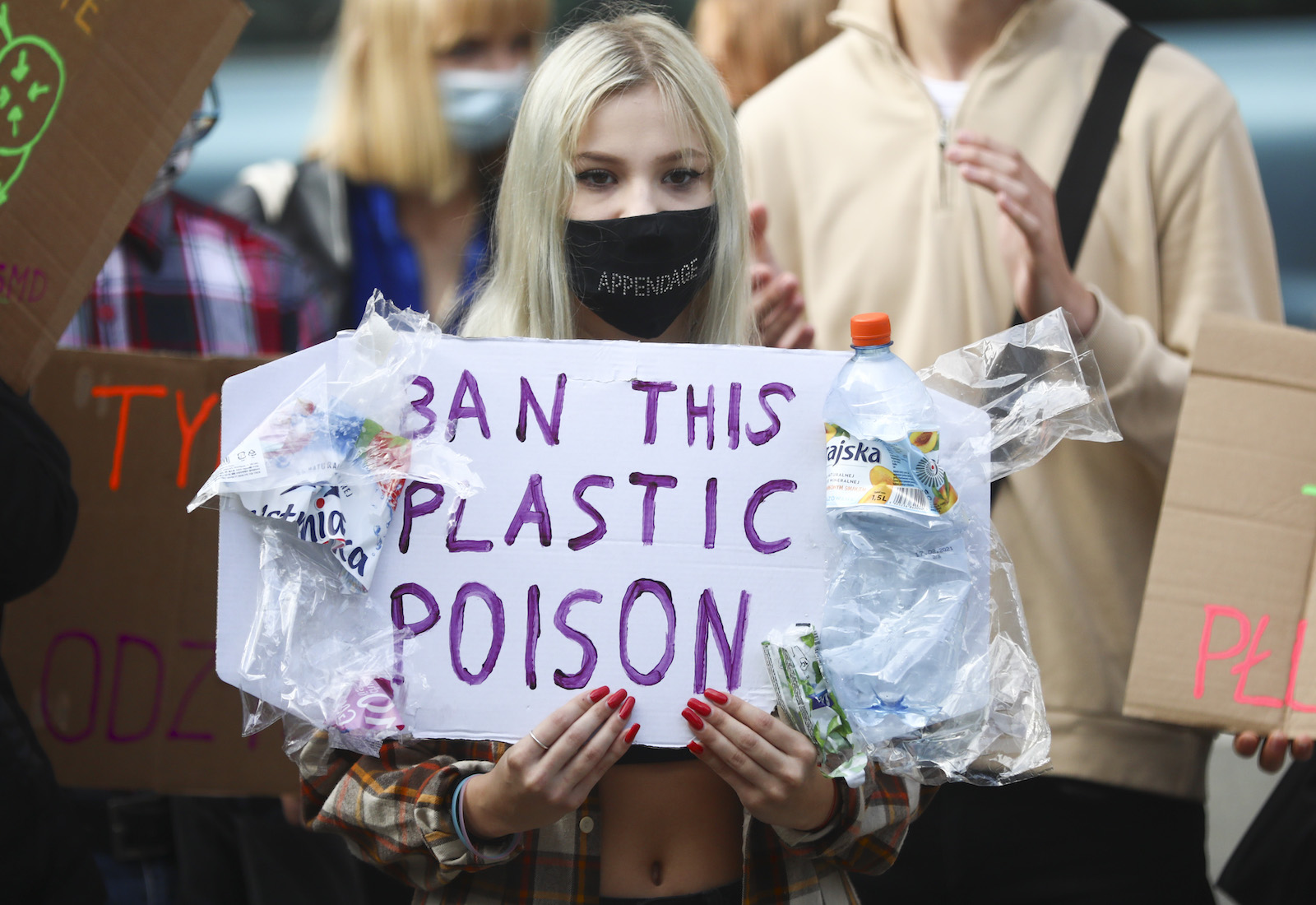

Negotiators from around the world will convene in Paris next week to continue working on a legally binding global treaty to address the plastics crisis. In this second of five rounds of talks, there will be much to discuss, including basic agenda items like the rules governing the negotiations. But for many who will be attending, one issue seems to have risen to the top of the priority list: toxic chemicals.

Since the first round of negotiations late last year, coalitions representing virtually every United Nations member state in Africa and Europe, as well as a dozen other countries including Canada and Australia, have put out statements calling for the treaty to include mandatory restrictions on chemicals in plastics. Other stakeholders have called attention to chemicals, too, with reports from many environmental groups and academics highlighting their risks to human health.

“We’ve seen a narrative shift” since the first negotiating session, said Bjorn Beeler, general manager and international coordinator for the International Pollutants Elimination Network, or IPEN, a coalition of public health and environmental groups. Once seen primarily as a litter problem, plastics are increasingly being recognized as a blend of hazardous chemicals that need to be controlled and phased out, he said.

“The plastics crisis … is a chemicals crisis,” Beeler added.

In some ways, the chemicals debate reflects the broader “battle lines” that have defined the global plastics treaty since countries agreed to negotiate it in March 2022. On one hand, countries like Peru, Norway, and members of the European Union have advocated for a treaty that protects human health and the environment, including by stemming plastic production. On the other hand, there are the lower-ambition countries, mostly oil-exporting states like the U.S. and Saudi Arabia. Some of these countries want the treaty to focus mostly on a concept called “plastics circularity,” basically a euphemism for recycling plastics and finding ways to keep them circulating through the economy. Currently, only about 9 percent of plastics are recycled globally.

Those in the first camp argue that plastics circularity is a dangerous distraction — and not only because it minimizes the need to reduce ballooning plastic production. When the U.N. Environment Programme published a report last week highlighting circularity for plastics, scientists and environmental groups said it would threaten human health, in part because toxic chemicals can be integrated into and then released from recycled plastic products. Jan Dell, an independent chemical engineer and the founder of the advocacy group The Last Beach Cleanup, tweeted that the report should have been titled “Mopping the #PlasticPollution Flood with Industry Myths.”

On Wednesday, Dell’s organization, along with IPEN and Greenpeace, published its own report claiming that “recycling plastics = recycling toxic chemicals.” The report synthesizes an extensive body of research showing how chemicals accumulate in recycled plastic products, whether from toxics-laden virgin material that is deliberately recycled, or from unintentional contamination in the waste stream. A recent analysis from IPEN, for example, found a hazardous plastic additive in every recycled plastic children’s toy and hair accessory it examined. Other research suggests that the recycling process itself can generate benzene, a human carcinogen.

There are many, many more plastics-related chemicals to be concerned about. Of the 13,000 chemicals commonly added to plastics, only 128 are regulated internationally, while 3,200 are known to have hazardous properties and some 6,000 more have never been assessed for toxicity. Recycling workers in the developing world are disproportionately endangered by these chemicals; they face heightened cancer risks and potential reproductive harm, among other health problems.

“Not only can we not recycle our way out of this problem, we probably shouldn’t,” said John Hocevar, Greenpeace’s oceans campaign director. A separate literature review published this week raised additional concerns about reusable plastic, whether or not it’s recycled. The review found that 509 chemicals can migrate from reusable plastic containers to the food they touch.

Christina Dixon, ocean campaign leader for the nonprofit Environmental Investigation Agency, agreed that chemicals have quickly become a priority in the lead-up to the negotiations in Paris. “The knowledge and awareness is really racing,” she told Grist, although it remains to be seen how that will manifest during the negotiations. By the end of next week, the U.N. is expecting delegates to have laid the groundwork for a “zero draft” of the treaty — a first attempt at the agreement’s actual text — so they can complete it before the next meeting at the end of the year. This will require diplomats to debate three potential objectives and several “core obligations” for the treaty that have emerged from countries’ pre-meeting submissions.

Dixon said she’ll be watching to see whether diplomats prioritize the two objectives that mention human health (the third focuses on waste and recycling), and whether they’ll weave protections from hazardous chemicals into the fabric of the zero draft. For the agreement to meaningfully protect human and environmental health, language related to health “needs to be everywhere” in the text, she said.

More specifically, a group of some 200 scientists called the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty has recommended that delegates support the creation of a global, comprehensive inventory of plastic chemicals, along with lists of those that are banned or permissible for use in plastic products. Because there are so many chemicals to deal with, they can be regulated more efficiently by grouping them based on their structure, rather than one at a time. “Once we know certain members of a group are hazardous, we would expect all the other group members to have similar properties,” said Martin Wagner, an associate biology professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and a member of the coalition.

Wagner also said countries should identify and begin phasing out “polymers of concern,” the kinds of plastic that are most likely to contain hazardous chemicals. These might include plastics like polystyrene, the plastic foam used in takeout containers and packing peanuts, and polyvinyl chloride, commonly used to make plastic water pipes. Both polymers can expose people to carcinogens and endocrine disruptors like styrene, benzene, tetrahydrofuran, and methylene chloride.

Additional priorities for the negotiations include setting up guardrails against chemical recycling — a process favored by industry groups that involves melting plastics into fuel, creating additional sources of chemical pollution — and requiring better labeling to disclose the chemicals used in plastics. Participation from developing countries, recycling workers, waste pickers, Indigenous people, and other nongovernmental observers is another issue to watch, and some countries have supported the creation of an interdisciplinary science advisory body to provide guidance on plastic-related chemicals.

As with the previous round of talks, environmental groups continue to support a global cap on plastic production, as well as a mandatory, top-down, and legally binding structure for the treaty, in contrast to the bottom-up approach that the U.S. is advocating for — where countries choose how they want to contribute to global plastic reduction. “We can’t afford to have a treaty that is largely voluntary and leaves the real work up to individual countries,” Hocevar said.

He returned to the idea of circularity, emphasizing the need for reusable and refillable systems to replace single-use plastics wherever possible. In this way, Hocevar said, “the circular economy is a really important thing for us to be striving for” — but without all the plastic. “The fact is that there’s no place for plastic in a circular economy.”