Food prices for the eurozone’s shoppers are set to continue rising at near-record rates for at least another year, despite the region’s large agriculture industry, according to a report by the European Central Bank.

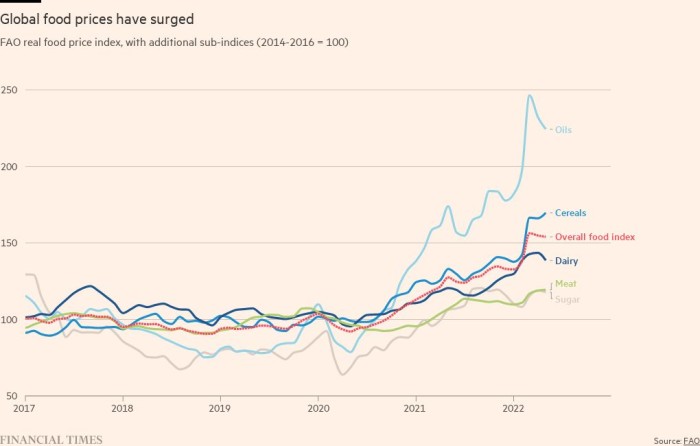

The EU produces more agricultural products than it consumes. But this has not insulated Europe from the surge in food prices that has swept across much of the world, driven by soaring fuel and fertiliser costs for farmers and the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on supplies of key products.

Food prices in the 19 countries that share the euro rose 7.5 per cent in the year to May, an all-time high since the single currency was launched in 1999. Annual food inflation is higher in the US and UK, but prices have been rising faster in the eurozone over the past three months.

The ECB said in an article from its monthly research bulletin published on Tuesday that food inflation was “expected to stay high in the coming months, despite some counterbalancing factors”, such as increased domestic production or a switch to alternative sources.

Pointing to a surge of more than 40 per cent in the farm gate and wholesale prices of food in the eurozone, the central bank predicted that further “price pressures will affect euro area consumer food prices through the pricing chain in the coming months”.

The soaring cost of fertiliser, which rocketed 151 per cent in the EU in the year to April, meant food prices would continue to surge in 2023, the central bank said.

Monetary policymakers would normally look past short-term rises in food prices as a supply-driven source of inflation that they have little influence over. But if food prices keep going up, people’s expectations that costs will continue to spiral could become entrenched. Consumers are more sensitive to sharp increases in their weekly food bill, because it is more easily noticeable than other costs.

Jennifer McKeown, head of global economics at Capital Economics, said policymakers “no longer have the luxury” of dismissing food inflation, “particularly since food prices are so visible and influential on the inflation psyche”. She forecast that if agricultural commodity prices kept rising it would cut consumer spending in advanced economies by 0.7 per cent.

The ECB announced this month that it would begin raising rates in July in a bid to combat inflation that, at more than 8 per cent, is now four times policymakers’ goal of 2 per cent.

The invasion of Ukraine, known as “the breadbasket of Europe”, has vastly reduced the country’s exports of wheat and corn as well as sunflower oil. The war also hit supplies of fertiliser from Russia and potash from Belarus.

The ECB said Ukraine, Russia and Belarus only accounted for a combined 2 per cent of the food and fertiliser imported into eurozone countries in 2020. But it added that the bloc still relied heavily on the supply of certain products from the three countries, such as maize, which is used widely for animal feed, sunflower oil and fertiliser.

Disruption to the supplies of fertiliser or maize were likely to push up the price of many other food products by raising costs for farmers, the central bank said. Alternative supplies of these products would be more expensive, it added.

“Households may substitute sunflower seed oil with other vegetable or animal oils and fats, but it is also used in a number of processed food products, so the reduced supply has a large impact,” it added.

In the Baltic states and Finland, which rely more heavily on Russia, Ukraine and Belarus for agricultural and fertiliser imports than most eurozone countries, food inflation has been well above the bloc’s average at between 12 and 19 per cent.

Even if food producers buy their ingredients from domestic farmers or those in other eurozone countries, they will still have to pay more due to the surge in global prices for many agricultural commodities and sharply higher energy and fertiliser costs for farmers, the ECB said.