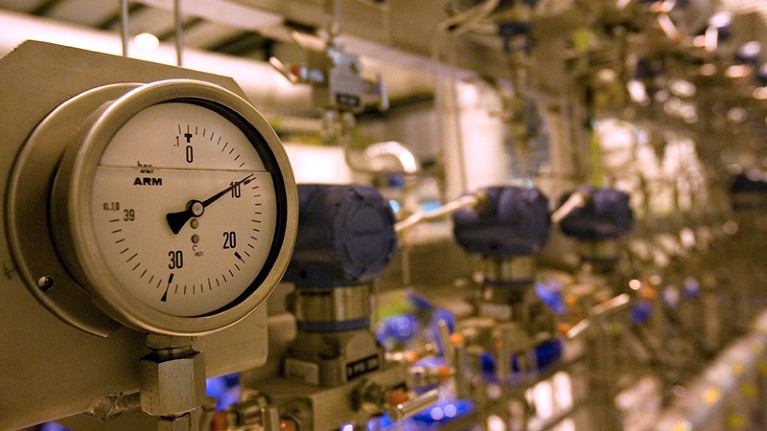

A pressure gauge at the Large Hadron Collider’s cryogenics, which take up more than half of the accelerator’s electricity consumption.Credit: Adam Hart-Davis/SPL

As energy prices spike as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, possibly causing a global economic downturn and stoking fears of rolling blackouts — especially in Europe — science laboratories are not being spared. The situation has raised particular alarm at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics lab outside Geneva, Switzerland, which already has massive energy bills in normal years.

On 26 September, CERN’s governing council agreed to significantly reduce the facility’s energy consumption in 2022 and 2023, after Électricité de France (EDF), a French electricity supplier, asked the lab to decrease the load on its network. The council decided to bring forward the lab’s annual year-end technical stop by two weeks, to 28 November, and to reduce operations by 20% in 2023 — which will be accomplished mostly by shutting down four weeks early next year, in mid-November. Operations will resume as planned at the end of February, in both 2023 and 2024.

CERN has also developed plans with EDF for reduced power configurations, in case energy use needs to be limited further in the coming months. Smaller measures are being taken to reduce overall energy use on the CERN campus, including switching off street lighting at night and delaying the start of building heating by one week.

Keeping cool

CERN’s flagship machine, the 27-kilometre-long Large Hadron Collider, is a major electricity glutton, in large part because of its 27-megawatt liquid-helium cryogenic system, the largest of its kind in the world. During normal operations, the annual electricity consumption of CERN is about 1.3 terawatt hours (for comparison, nearby Geneva uses around 3 terawatt hours per year). Yearly maintenance periods for the LHC are scheduled during the winter months, to save on its bills. Consumption falls to about 0.5 terawatt hours during longer shutdowns, as happened in 2020–22. After extensive upgrades, the LHC restarted in April, and the total electricity cost is expected to be about 88.5 million Swiss Francs (US$89 million), says Joachim Mnich, director for research and computing at CERN. The reduction in operations will lower that significantly next year, although not by the full 20%, because the accelerator magnets still need to be kept cool while the facility is offline.

The move will help to save money amid rising energy prices, but Mnich says cost was not the main driver of the decision. Natural gas is the primary source of electricity and heating in the winter in much of Europe, and the CERN council wants to reduce their use of the limited supplies, leaving more for people to heat their homes. “This is something we do not primarily to save money, but as a sign of social responsibility,” he says.

The longer shutdowns will affect the scientists who rely on CERN’s other accelerators for their experiments. Those that were scheduled for the last two weeks of this year’s run will have to be postponed until next year, and the competition for the reduced beam time next year will be fiercer than usual, says Mnich. The total number of proton–proton collisions in the LHC will be lower than normal this year and next, but Mnich does not expect that to have a huge effect on the science. “On the scale of the whole of run 3, which goes until the end of 2025, there will probably only be a small effect,” he says.

Energy prices are also rising significantly in the United Kingdom, although institutions there would not say how this will affect their operations in the short term. A spokesperson for Imperial College London says that, although the university, like all large organizations, is affected by the rising cost of energy, “we are confident in our resilience and ability to respond to the challenge”. The Science and Technology Facilities Council, which runs several large facilities, including the Diamon Light Source in Didcot, says all of its facilities “have been working on energy-reduction plans for a number of years to meet their net-zero commitment and reduce cost”.

Tightening belts

The German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg is also affected by higher prices. The facility buys much of its electricity in tranches up to three years in advance, to hedge against sudden price spikes. So it has already procured 80% of its energy needs for 2023, 60% for 2024 and 40% for 2025. But the lab will need to make a decision soon on whether to buy the remaining 20% for next year, says Wim Leemans, director of the accelerator division. “At current prices we are not able to afford it,” he says.

DESY is in talks with the German government to seek extra funding to maintain operations, which are making important scientific contributions to areas that are essential to the future of Europe, such as the development of COVID-19 vaccines, battery technology and solar power, Leemans points out. But its managers are also preparing for the worst. Next week, they will run tests to see how running instruments such as the European X-ray Free-Electron Laser and PETRA III synchrotron at lower power settings would affect experiments. And as a last resort, DESY is also considering a longer winter break, like CERN is. “We are doing everything we can to make sure our 3,000 users are not left out to dry,” says Leemans.

Research facilities in other parts of the world are also dealing with rising energy costs. Bill Matiko, chief operating officer of the Canadian Light Source (CLS) in Saskatoon, says electricity costs make up a “significant” part of the lab’s annual budget, at around 8%. Although Canada’s domestic energy production, especially of natural gas, means the situation there is not as dire as in Europe, prices are still on the rise owing to high inflation — electricity rates went up by 4% on 1 September, and will go up again by another 4% by 1 April next year. About half of that increase had been anticipated and budgeted for, says Matiko. “It’s something we can somewhat easily accommodate by moving things around in the budget,” he says.

The CLS, like many big, energy-intensive facilities, has been working to improve its energy efficiency over the past several years, says Matiko. For example, all lights at the facility were replaced with LED bulbs, and cryo modules were switched to new superconducting cooling devices that are much more energy efficient. “Those have significant savings in terms of power consumption,” he says. “The energy bills are a fraction of what they would be otherwise.”

Labs in North America, such as CLS, will not need to reduce operating time, but they probably will not be able to accommodate European scientists who are losing beam time. CLS is already oversubscribed, says Matiko. With the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago, Illinois, shutting down in April 2023 for at least a 12-month upgrade, beam time in North America is about to be constrained as well. “Already, some APS users want access to our beams,” says Matiko. “There’s going to be a big increase in demand for us and for others.”