Oil prices have renewed their rise in the most sustained ascent since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a fuel supply crunch adds pressure to a market that had already been disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic.

The disturbance to flows of oil and related products from Russia has rippled through energy markets as refineries are racing to pump out petroleum products to meet the needs of a global economy that is still emerging from the shock of Covid-19.

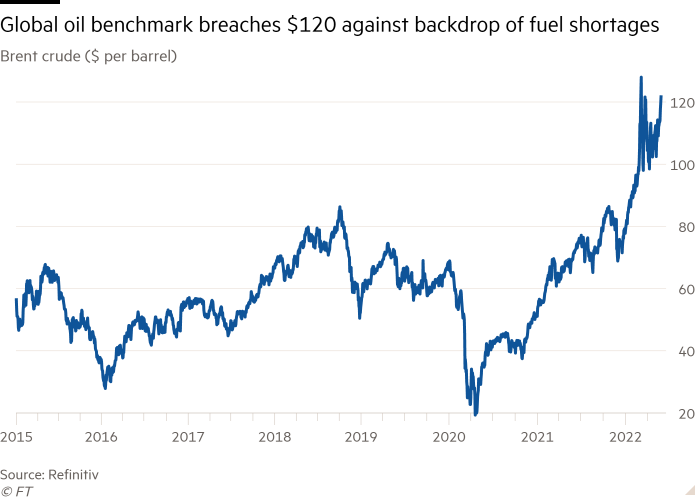

The supply and demand imbalances pushed the price of Brent crude, the global benchmark, up by more than 10 per cent last month in the biggest rise since January. Brent for July delivery hit a high of $123 on Tuesday compared with less than $80 at the start of this year.

The rise underscored persistent supply challenges in the market for refined products such as gasoline and diesel, which had been building even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February.

“The crude oil price is $120 per barrel but the product price — what you and I pay for petrol and diesel — is much, much higher. The overarching theme is the lack of investment,” said Amrita Sen, founding partner and chief oil analyst at Energy Aspects.

“We are in this for the long haul: potentially a decade.”

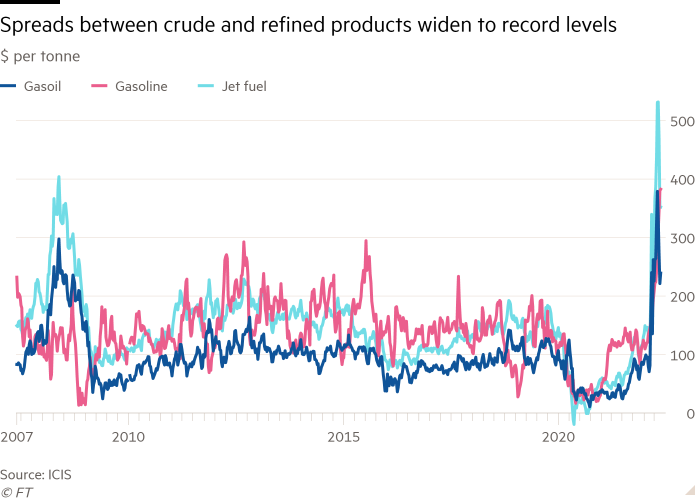

Oil analysts said that a shortage of processing capacity had compounded an extreme squeeze on the availability of products such as diesel, gasoline and jet fuel, incentivising refineries to lift output and thereby increase demand for crude.

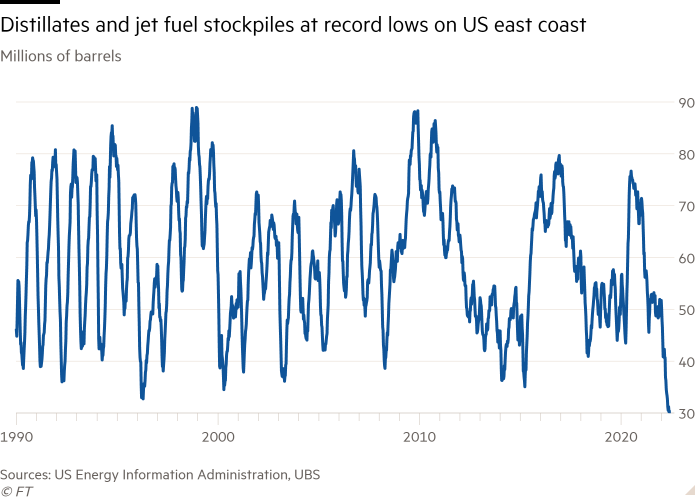

The closure of 2.8mn barrels per day of refinery capacity in the last two years on the grounds that it was surplus to requirements during the coronavirus pandemic — and for environmental reasons — has left the oil processing sector struggling to meet demand during the current maintenance season. Compounding the situation, China has restricted fuel exports at a time of record low inventories in certain parts of the world.

Crude remains well below its 2008 all-time high of $147.50 a barrel, but prices at the pump have hit unprecedented levels because consumers pay to cover the margins of refineries that process crude into fuel and the distributors and retailers that market them.

There is a bigger shortfall in diesel and gasoline markets than crude, so prices for refined products have climbed faster. The gas oil contract in Europe, a proxy for diesel and other distillates, is trading close to record levels near $1,250 a tonne.

Refineries have vowed to ramp up throughput, thereby boosting crude prices and narrowing the difference between crude and refined product prices that had widened to record levels.

The increased demand for crude comes as the oil market faces other upwards pressures on demand. China is easing lockdown restrictions in Shanghai and the summer uptick in travel demand is picking up pace.

Rick Joswick, head of global oil analytics at S&P Global Commodity Insights, said that “it is a race between demand increasing seasonally and refiners increasing their operations to produce the fuel”.

Oil markets also face fresh threats to supply after Iran seized two Greek tankers last week, dimming the possibility of any breakthrough on the Iranian nuclear deal, which would pave the way for a return of the country’s oil supplies to global supply chains. The move may additionally curb the free flow of oil out of the Middle East by other producers such as Iraq.

“And in the background, we are concerned about Russian supply,” said Caroline Bain, chief commodities economist at Capital Economics.

The EU struck a deal late on Monday to ban seaborne Russian oil imports. But Lars Barstad, chief executive of tanker company Frontline, said on an earnings call that 2mn barrels of oil were already being diverted daily, equivalent to 6 per cent of the global seaborne oil trade.

Russian crude oil has managed to find plenty of willing buyers in China, India and Turkey and exports have even increased over prewar levels.

However, Russian exports of refined products slumped to a 22-month low in May, according to Vortexa, leading local refineries to cut production. About 1.3mn b/d of Russian refinery capacity are expected to be offline through to the end of 2022, JPMorgan estimates, although other analysts say a seasonal drop in Russian fuel exports is nothing unusual.

The uncertainty over the ability of Russia to get its oil to market — particularly if the EU sanctions insurance for tankers trading Russian oil — has left oil prices vulnerable to volatile upswings. Bank of America has predicted that a sharp contraction in Russian oil exports could trigger a “full-blown 1980s style oil crisis” and push Brent crude prices above $150 a barrel.

Some are less bullish on prices in the longer term. Amy Myers Jaffe, managing director of Climate Policy Lab at the Fletcher School at Tufts University, said that the potential removal of Russian oil from the market evokes memories of the 5mn b/d loss of Iraq and Kuwaiti oil from global markets in 1991.

She added that the rise in prices would eventually lead to a “cataclysmic drop” because of demand destruction, a recession or government action towards alternative energy sources — which was not a feasible option during previous oil shocks.

“It’s a cycle and it’s still a cycle. Cycle means it’s going to come down,” she said.

But Giovanni Staunovo, commodity analyst at UBS, said an immediate recession seems unlikely with the easing of Covid restrictions igniting fervour for travel among consumers.

“The only negative element I see is the pandemic limiting the demand,” he said. “Potentially prices need to go even higher to rebalance the market.”