Last week, we looked at how an illegal document purge in Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office blocks freedom for the wrongfully convicted. This week, we explore how the missing prosecutor files have impacted cases in which police illegally withheld exculpatory evidence.

The body of Lenny Thompson was found on the side of a road at Rouge Park in Detroit in August 1988, wrapped in layers of curtains, clothing, a bed sheet, and a blanket, and fastened with a rope and a drape.

Thompson had been stabbed 12 times with a four-inch blade.

Over the next week, Detroit police illegally arrested 28 potential witnesses without warrants and questioned five more, according to records obtained by Metro Times.

What detectives gathered were numerous potential motives, contradictory eyewitness accounts, and at least six different suspects.

Most people described Thompson as a crack dealer with a temper and a lot of enemies. A couple of weeks before he was murdered, he used a machete to chop off the hand of a drug customer who complained that he was shorted in a dope deal with Thompson, according to multiple witnesses. And about a month before Thompson’s body was found, he shot at a man named Jay whose house he had been staying at on Chapel Street on the city’s west side, according to his neighbors, friends, and associates.

At that house less than a day before Thompson’s body was found, two witnesses told police they saw Jay and his friend carrying what appeared to be a body wrapped in blankets. One of the witnesses, known as Madonna, said she also smelled an awful stench inside the house, and one of the occupants who was “acting strangely” insisted it was from a dead dog.

Despite these accounts, police and Wayne County prosecutors claimed that Thompson was killed at a different house by other people, including Mark McCloud, who was charged with Thompson’s murder.

Alarmingly, neither McCloud nor his attorney were informed of the contradictory evidence, despite his constitutional right to access it. He discovered through a public records request that all witness statements challenging the allegations against him had been withheld.

Police and prosecutors are constitutionally required to turn over exculpatory evidence, which is any information that shows that a defendant is innocent. Defendants who prove that exculpatory evidence was withheld during their trial are entitled to a new one under the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brady v. Maryland ruling. Withholding exculpatory evidence is called a “Brady violation.”

Of the 33 witnesses questioned by police, only five of them testified at McCloud’s trial, and all of their testimony fit the prosecutor’s narrative.

Without any physical evidence tying him to the scene, McCloud was convicted of murder and kidnapping and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

About two years ago, with the help of an attorney, Rachel Wolfe, and a private investigator, Scott Lewis, McCloud received a copy of his unredacted police file. It showed that police withheld a secret file that contained interviews with more than two dozen witnesses who threw his guilt into serious question.

“I would never have come to prison if they turned this information over,” McCloud tells Metro Times from the G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility in Jackson. “You have no recourse to fight when you have officers withholding exculpatory evidence. I wrote the judge in the case at least 20 times, same with the Detroit Police Department and the prosecutor. And I got nothing.”

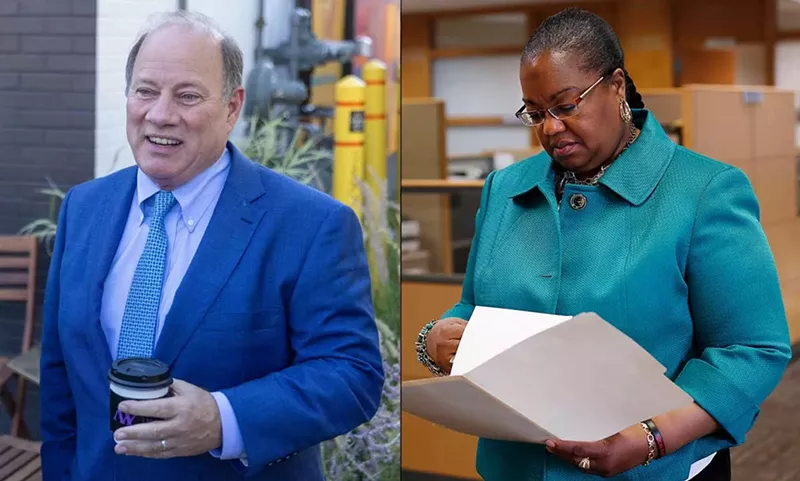

McCloud’s case has been complicated by the fact that the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office destroyed thousands of records from 1995 and earlier in violation of a state law that requires prosecutors to retain files for at least 50 years, as reported last week by Metro Times. The records were allegedly destroyed when Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan was prosecutor between 2001 and 2004, according to the current prosecutor, Kym Worthy.

Without those records, McCloud faces a steeper challenge convincing a judge of his innocence. For example, it’s easier for him to prove that police withheld exculpatory evidence from prosecutors if he could compare their files to the police records.

“It matters in these old cases because we compare the prosecutor files with the police files,” Wolfe says. “As we know in the ’80 and ’90s, [police] set aside miscellaneous files that they didn’t share with the prosecutor. If I don’t have the prosecutor file, I have no idea what they had.”

Wolfe is asking a judge to overturn the conviction based on the withheld exculpatory evidence.

“I think the Brady violation is huge. I believe he is innocent,” Wolfe tells Metro Times. “My argument is that he didn’t get a free trial because of the Brady violation, and he couldn’t present the exculpatory information.”

To strengthen McCloud’s case, Lewis tracked down some of the witnesses who gave statements that contradicted the official version of events. One of them, Derrick Ali, said in an affidavit that he saw two men lugging what appeared to be a heavy, rolled-up rug out of a house where Thompson sold drugs. It was not the house where police and prosecutors alleged Thompson was killed.

Ali said he was surprised authorities didn’t call him to testify or ask him follow-up questions.

“I never heard from the police again,” Ali said in the affidavit. “I expected to be called into court to testify but I was never contacted and asked to testify. If I had been asked to testify, I would have testified truthfully to everything that I knew and saw.”

Steve Neavling

This is the block of Chapel Street where witnesses say they saw two people carrying a heavy, rolled up rug that could have been the body of Lenny Thompson. The block is almost completely vacant now.

Miscellaneous files

McCloud is just one of many prisoners to find out that police withheld evidence that may have acquitted them. In the 1980s and 1990s, Detroit homicide detectives illegally withheld records in what they called a “miscellaneous file” that was concealed from prosecutors because it contained exculpatory evidence.

Although not widely reported in the media, the existence of the miscellaneous files made waves in prisons and the legal system, raising hopes that innocent inmates could now prove they were wrongfully convicted.

The misconduct was first brought to light in September 1996 when defense attorney Sarah Hunter met surreptitiously with a former FBI agent and a suspended Detroit police officer, Ritchie Harrison, in a parked car outside a Highland Park grocery store. Harrison revealed that Detroit homicide detectives maintained unlawful “miscellaneous files” used to withhold exculpatory evidence in murder cases, according to an affidavit signed by Hunter in 2004, after Harrison and the agent died.

Harrison also described how officers were instructed to fabricate details and destroy evidence to secure convictions, often framing innocent people in the process.

The miscellaneous files contained witness statements, alternative case theories, and the names of other suspects, along with potentially exonerating and impeaching evidence that could hurt the police department’s case. For police, the files effectively ensured that only incriminating evidence was presented when they requested that prosecutors file criminal charges.

When information about the miscellaneous files became known to inmates, defense attorneys, and private investigators in 2004, the police department became inundated with public records requests for the miscellaneous files. And sure enough, the files existed in many cases, and they often included exculpatory evidence.

But the full extent of the misconduct is unknown, in large part because the destruction of the files has stymied efforts to uncover what police withheld from prosecutors, depriving potentially innocent people of freedom.

Hunter used the information to help exonerate Dwight Love, a Detroit man who was wrongfully convicted of murder in 1982. Love’s conviction was overturned, and he was granted a new trial in 1997. Although prosecutors initially sought to retry him, the charges were ultimately dismissed in 2001. Love was released but died in Detroit in 2014.

Steve Neavling

The body of Lenny Thompson was found on the side of a road at Rouge Park in Detroit in August 1988.

Rampant police misconduct

For this story, Metro Times interviewed about a dozen inmates who say Detroit police withheld exculpatory evidence in miscellaneous files that were not turned over to the defense. All of the prisoners maintain they’re innocent and that the miscellaneous files would lead to their acquittal if they were charged today.

Indeed, many of the miscellaneous files obtained by Metro Times contain information that contradicts the prosecutors’ cases. Much of the information is compelling and ultimately denied the young men of their constitutional right to mounting an adequate defense when they were on trial for murder.

Without access to the prosecutor’s files, the prisoners cannot show whether or not the potentially exculpatory evidence from police was withheld from prosecutors.

“You really need to get all the cards on the table,” Lewis, an investigative journalist-turned-private investigator, tells Metro Times. “The fact that they withheld all these files creates serious problems, especially if you can’t compare them to the prosecutor’s records.”

Lewis adds, “The thing that is important for the prosecutor’s file is, if you’re looking for a Brady violation for withholding evidence, you’re looking to see what the prosecutor saw and what’s in the police file that wasn’t in the prosecutor file.”

During his career as a private investigator, Lewis says he’s handled 15 to 20 cases in which prisoners “told me they got things from the miscellaneous file that they never saw before.”

The file purge, coupled with the miscellaneous police files, is especially troubling because it involved records from a deeply problematic period in Detroit’s Homicide Division, when rampant misconduct, coerced confessions, and constitutional violations by police, particularly homicide detectives, were so widespread that the U.S. Department of Justice intervened, pressing for reforms to avoid a costly lawsuit in the early 2000s. This era of misconduct led to a significant number of wrongful convictions and false confessions, evidenced by a surge in exonerations and court settlements. Legal experts say many innocent people remain incarcerated, but the destruction of the prosecutor’s files has compromised many of their cases, leaving some prisoners without a clear path to proving their innocence.

“It was like the Wild West in the ’80s, ’90, and early 2000s,” Lewis says of the police department. “They did whatever the hell they wanted down there. It’s a very serious problem.”

City of Detroit (public domain), Associated Press (Paul Sancya)

Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy, right, claims thousands of records from 1995 and earlier where illegally destroyed under her predecessor, now-Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan.

False narratives

When Tommie Lee Seymore was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison in 1990, he was just 19 years old and adamant that he was innocent.

Prosecutors built a narrative that Seymore was a drug dealer that killed 26-year-old Nathaniel “Pops” Cunningham after he demanded Seymore’s associates stop selling narcotics. Prosecutors portrayed Cunningham as a good Samaritan who was “trying to rid the community of drugs,” according to trial transcripts.

But according to police records withheld from Seymore during his trial, Cunningham was far from a moral crusader, and plenty of people had reasons to kill him. He was a drug dealer and had previously been arrested for a jail escape and assaults, including the murder of a gang member in September 1988, the records state.

“The deceased wasn’t a good guy like they painted,” Seymore says in an interview from the G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility in Jackson. “Other people wanted him dead.”

Police withheld compelling evidence that suggested a notorious gang, Best Friends, was responsible for Cunningham’s murder.

At the time of his death, Cunningham was in the midst of a war against Best Friends, which was known for large-scale drug sales, contract killings, and drive-by shootings, according to police reports. He was previously charged with robbing and murdering one of Best Friends’s members Tommy “Peewee” Hayes, but he was acquitted after the prosecution’s star witness disappeared, according to court records.

The murder also fit the modus operandi of Best Friends: Cunningham was ambushed and gunned down by an AK-47, and his rear tires were flattened, the hallmarks of the gang’s attacks.

The gang’s notorious former hitman, Nathaniel “Boone” Craft, who admitted to police that he murdered at least 30 people, swore in an affidavit in January 2020 that Cunningham’s murder fit his and his partner’s operating style.

“I also determined that this murder exactly fit the method of operation my partner and I used when we committed murders for the Best Friends gang,” Craft said in the affidavit. “We would determine the target’s routine, hide and lie in wait until the victim was leaving and arriving at the location. We always approached the victim’s car from the rear and opened fire with an AK47. The AK47 was powerful enough to go through car doors, seats or anything else that might give the intended victim protection.”

Craft said his partner in crime, Charles Wilkes, may have murdered Cunningham “because he was in possession of the AK-47 that night.” Wilkes said a simple ballistics test could prove their weapon was used in the murder.

According to Seymore’s request for a new trial, the miscellaneous files “show an elaborate act of suppression by the DPD to keep Mr. Cunningham’s true criminal arrest record from the defense. The deliberate suppression of evidence by the DPD denied Mr. Seymore of his right to a fair trial. … The suppressed evidence would have given Mr. Seymore an opportunity to present the complete defense.”

Seymore received the miscellaneous files from the Detroit Police Department in 2017, and he was floored that investigators had withheld evidence that he believes would have acquitted him during his trial.

Seymore hoped to prove that prosecutors never received the exculpatory evidence but their records have been destroyed. He also wanted to know if prosecutors had additional suspects and motives.

“Did the prosecutor have that information? Did they withhold that information from me?” Seymore asks.

In May 2017, Barbara Brown, a public records officer for the prosecutor’s office, revealed in a letter to Lewis, his private investigator, that Seymore’s file was likely “included in the confidential destruction” of records from 1995 and earlier.

When he first learned about the file purge, Seymore says, “I was devastated, but I wasn’t deterred. I remained vigilant because I still have the miscellaneous files.”

Steve Neavling

The Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office recently moved to the Wayne County Criminal Justice Center in Detroit.

‘Moe did it!’

On Christmas afternoon in 1991, Donald Elliott was engulfed in flames, and his dying words to Detroit firefighters and medics were, “Moe did it, Moe did it,” according to police records.

Moe is Mario Lee Brown, one of two men eventually convicted of murdering Elliott.

According to prosecutors, Brown and James Goodman attacked Elliott because he owed them money and wasn’t paying them back. Goodman was allegedly armed with a handgun, beat Elliot, and doused him in charcoal lighter fluid.

“Light that motherfucker up,” Brown allegedly commanded.

Using a butane lighter, Goodman set Elliott on fire, prosecutors alleged. Elliott ran to the rear of the house engulfed in flames, which spread to the house and caused significant damage. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

After Goodman and Brown were convicted and sentenced to prison, one of the prosecution’s key witnesses cast doubt about his trial testimony, saying in an affidavit that detectives bombarded him with so many lies that he eventually began to believe them. Also, three of the prosecution’s witnesses were “heavy drug users,” Goodman says.

That’s important, he explains, because there was no physical evidence tying him to the scene.

According to firefighters and medics who talked to Elliott before his death, he never mentioned Goodman’s name.

Goodman says he has three witnesses who can confirm he was nowhere near the scene when Elliott was killed.

But building a case for his innocence has been especially difficult since both the prosecutor’s office and the 36th District Court told him his records were destroyed.

He wants to prove that prosecutors violated his constitutional rights by denying him a probable cause hearing and that exculpatory evidence was withheld. He has other questions: Whom did Detroit police interview? Were any of the witnesses promised anything in return for their testimony? Were there alternative suspects and motives? Was he offered a plea deal he wasn’t told about?

“The destroying of my prosecutor’s file has left me with no way to prove my factual innocence,” Goodman says from the G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility.

“Since the 36th District Court file and my Wayne County prosecutor’s file have been destroyed, why am I in prison [when] there’s no factual documentation of me being involved with any crime?”

‘Why?’

Even when inmates have compelling evidence that they were wrongfully convicted, they often spend years waiting for a court to take up their case.

After 30 years in prison, McCloud may finally get his chance to prove his innocence. In April, Wolfe filed a motion requesting the 3rd Circuit Court in Detroit to overturn McCloud’s conviction, citing, among other things, the new evidence discovered in the police department’s miscellaneous files.

In a hopeful move for McCloud, Wayne County prosecutors conceded that he should receive an evidentiary hearing so a judge can consider the new evidence, Wolfe says.

McCloud has been waiting for this day since the prison door clicked behind him in February 1989. He says he has pleaded his case in letters to judges, prosecutor, and police “at least 20 times each” for many years, but to no avail.

Describing the challenges he faced in trying to access his records, McCloud said, “it’s easier to chew nails” than to obtain the police and prosecutor files.

Now, all he has is time to wait.

“I just sit in the yard and look up at the sky and just say, ‘Why?’” McCloud somberly adds, “My family wants me home.”