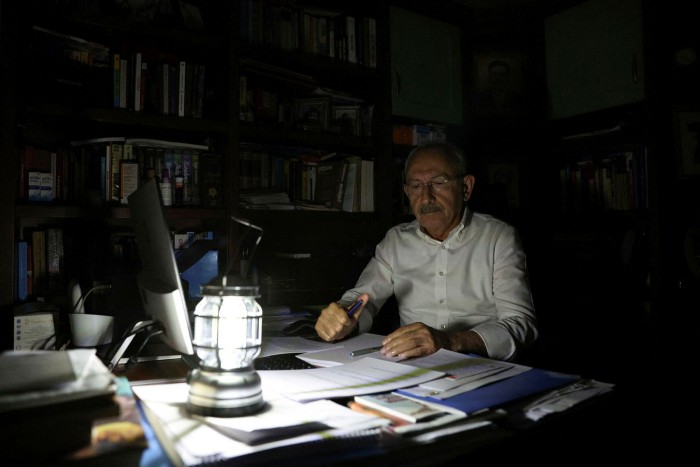

If there were any doubts about Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s determination to be the man to take on Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, they were dispelled when he took the podium of the nation’s parliament last week.

Addressing fellow members of his Republican People’s party (CHP), the bespectacled 73-year-old declared he was gunning for a “big fight” against the rising poverty, crushing inflation and painful injustice that are ravaging the country. With a critical election due within the next 13 months, he warned unnamed rivals within his opposition alliance: “Either join me or get out of my way.”

The former bureaucrat, who has led the party of Turkey’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, since 2010, has undergone a transformation in recent years. Long mocked by Erdoğan as a serial loser at the polls, he oversaw a stunning victory in municipal elections in 2019 when the opposition won control of Istanbul, Turkey’s biggest city, and Ankara, its capital.

Most importantly, he is credited with building and holding together a diffuse alliance of opposition parties united behind the goal of defeating the man who has spent almost 20 years at the country’s helm, first as prime minister and then as president.

That decision to work together — combined with simmering public discontent over the state of the Turkish economy and growing unease about the country’s 3.6mn Syrian refugees — offers the president’s rivals their best ever chance of victory, according to political analysts.

Berk Esen, a visiting fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin, believes conditions should be ripe for a historic change. “The ruling party is divided, you have the opposition coming together. The economic situation is really worsening and I don’t see how Erdoğan can reverse this cycle,” he says.

And yet, with the crucial vote due sometime before June 2023, there is growing concern that the alliance risks squandering the opportunity that lies before it.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has amplified the misgivings. Although the war has put fresh strain on the Turkish economy, which risks being hit by soaring oil and gas prices, it has also boosted the importance of Turkey in the eyes of fellow Nato members after years of tension with the west.

Erdoğan has taken the opportunity to play a role as mediator between Kyiv and Moscow and, while striving not to anger Vladimir Putin, has limited the Russian military’s use of Turkish waters and airspace. A defence company co-owned by his son-in-law supplied armed drones to the Ukrainian armed forces. The Turkish president enjoyed a small bounce in the polls in March as the crisis burnished his image as an important international player, though there are signs this is already fading.

The outcome of last month’s Hungarian elections, where an alliance of six opposition parties failed to beat Viktor Orbán, offered further warnings. “If you asked me last year, I would have said: it’s in the bag, Erdoğan is going to lose,” says one opposition official. “Now I’m much less sure.”

Statesman, firebrand, kingmaker

The biggest fear for some in the opposition is that Kılıçdaroğlu will insist on nominating himself to run against Erdoğan — and that the Turkish president will eat him alive.

Kılıçdaroğlu “is dying to run”, says a senior official from one of the five other opposition parties working together with the CHP. “I have no doubt that he would make the best president of all of the possible candidates. But he has the lowest chance of winning.” Esen sees Kılıçdaroğlu as “a great kingmaker” but argues: “He’s not a king.”

Whoever is chosen to run against the Turkish president will face a wily and experienced politician who remains one of the country’s most popular political figures despite ushering in runaway inflation that reached 61 per cent in March.

In recent years, Erdoğan has gained unprecedented control over Turkey’s institutions, from the courts to the central bank, and has repeatedly used those powers to manipulate the electoral system in his favour. In March, he changed the country’s electoral laws in a way that could politicise the oversight of vote counts.

The last two attempts to defeat him in a presidential contest failed miserably when the largely secular opposition failed to win over his religious, conservative base, even as younger and more urban voters grew disillusioned with his government. The last time the opposition fielded a joint presidential candidate, in 2014, Erdoğan won by a 13-point margin.

Yet opinion polls consistently suggest there are two potential candidates who could secure a clear win in a head-to-head race against the 68-year-old president. They are Mansur Yavaş and Ekrem İmamoğlu, the opposition mayors of Ankara and Istanbul.

Yavaş, 66, has achieved sky-high approval ratings by focusing relentlessly on improving public services in a city that was for years run by an eccentric Erdoğan ally who wasted public money on statues of dinosaurs and a giant theme park.

The presidential contenders

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, 73

Leader of the Peoples’ Republican party (CHP)

Fans say: Elder statesmen perfectly placed to hold together a diverse alliance of parties — and to oversee the return to a parliamentary system.

Critics say: He cannot win.

Ekrem İmamoğlu, 51

CHP mayor of Istanbul

Fans say: Popular, energetic politician who can appeal to religious conservatives and Kurds.

Critics say: His personal ambition risks upsetting the delicate balance in the alliance.

Mansur Yavaş, 66

CHP mayor of Ankara

Fans say: Has gravitas and the ability to pull conservatives and nationalists away from Erdogan’s ruling alliance.

Critics say: As a former member of an ultranationalist party, he will struggle to win over Kurds.

Conservative and nationalist, but also reserved and statesmanlike, Yavaş is well placed to win over Erdoğan voters, his supporters argue. He could also oversee the opposition’s plan to abolish the presidential system of governance that Erdoğan instated in 2018 and restore the role of parliament.

“He could be a great father figure to go down in history as the guy who put Turkey back to a normal regime,” says Suat Kınıklıoğlu, a former ruling party member of parliament who ran one of Yavaş’s previous electoral campaigns. “He would be willing to play that role.”

Most political analysts, however, see İmamoğlu as the stronger candidate. The 51-year-old, a self-described social democrat who can recite from the Koran, is more overtly political and has the potential to appeal to a broader spectrum of voters.

“He’s popular, he’s young, he’s energetic. He can handle Erdoğan and Erdoğan would look old facing him,” says Ali Çarkoğlu, a political scientist at Istanbul’s Koc University. “He loses his temper from time to time but that’s even a good selling point in Turkish politics.”

İmamoğlu has also chalked up experience of fighting contested elections. That matters when many in the opposition are fearful that Erdoğan will resort to underhand tactics in a bid to hang on to power. In 2019, when İmamoğlu was narrowly elected mayor of Istanbul, a job Erdoğan himself used as a springboard into national politics, the president cancelled the results of the election, claiming fraud. İmamoğlu won the rematch by a landslide.

But the mayor’s opponents claim he is “too ambitious” to be trusted with the task of dismantling the powerful executive presidency Erdoğan has built for himself — a job that would require the winning candidate to work actively to undermine the importance of their own role.

“He could be another Tayyip Erdoğan,” says a senior official at one of the smaller opposition parties. “No one wants that. Once you’re in that job, with all those powers, you can do anything you want.” Asked to comment on that jibe, a person close to İmamoğlu said his only shared traits with Erdoğan were a Black Sea heritage and a stint playing football in his youth. “Apart from those two things, they have nothing in common.”

Besides the statesman Yavaş and the populist İmamoğlu stands the more technocratic Kılıçdaroğlu. Though it is rarely openly discussed, many believe that the fact that Kılıçdaroğlu hails from Turkey’s Alevi minority — which has a long history of tensions with the Sunni Muslim majority — would be ruthlessly exploited by Erdoğan to mobilise his base.

Though he has recently discovered a taste for acts of civil disobedience — such as refusing to pay his electricity bill in protest at rising prices — critics say he lacks the charisma to energise the electorate and beat a street fighter like Erdoğan. Kılıçdaroğlu and his allies counter that popularity should not be the sole criteria. “We are not electing a pop star,” he told journalists in December. “It needs to be someone who can both hold the alliance together and oversee the transformation of the state.”

Even so, for the state to be transformed, the opposition must first win power — and there are plenty who say they must not only win, but win big to avoid the messy scenario of a contested outcome.

“It’s not at all clear that Erdoğan is willing to step down if he loses,” says one western diplomat. “It could be very fraught — especially if the result is close.”

Horse-trading

The final decision will ultimately come down to a behind-the-scenes negotiation between the group of opposition leaders known as the “table of six”. As the second most powerful leader at that table, Meral Akşener, head of the rightwing IYI party, will play a critical role. She has ruled herself out as a presidential candidate, saying she would prefer to be prime minister in a future opposition government.

According to one senior IYI official, Akşener is eager to field a challenger who could easily beat Erdoğan in the first round of a presidential race, rather than risking a run-off. There are signs she favours İmamoğlu, whom she last year compared to Mehmed the Conqueror, the Ottoman Sultan who captured Constantinople in 1453. But like her counterparts in the smaller parties of the alliance, she must make a complicated calculation about which candidate can win and which best suits her own political ambitions.

Beyond the horse-trading, a key consideration is the need to appeal to Turkey’s large Kurdish minority. The pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic party (HDP), which is expected to secure around 12 per cent of the national vote, is not part of the alliance — it is considered too toxic, especially by the rightwing parties, due to what the government calls its links to an outlawed Kurdish militia.

The power brokers

Meral Akşener, 65

Leader of the rightwing IYI party

Has ruled herself out as a presidential candidate but could play crucial role in deciding the nominee. Must balance her own desire to become a powerful prime minister in a future coalition government (easier with a weaker president) with the need to pick a strong winner.

Selahattin Demirtaş, 49

Jailed former leader of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic party (HDP)

Iconic among the country’s Kurdish voters, he ran in the 2018 presidential election from his prison cell. Could choose to throw his weight behind a joint presidential candidate, upping their chances of beating Erdoğan in the first round.

But any opposition candidate will need the HDP’s blessing, which explains why Erdoğan has sought to drive a wedge between it and the rest of the opposition. A fresh military operation launched against Kurdish militants in Northern Iraq in April, and broadly supported by every major party except the HDP, is already serving that purpose.

Of the three men, Kılıçdaroğlu or İmamoğlu are more likely to appeal to the HDP base, according to Reha Ruhavioğlu, director of the Kurdish Studies Center in the Kurdish-majority city of Diyarbakir. Yavaş, the Ankara mayor, is a former member of an ultranationalist party, which would probably alienate Kurdish voters. The HDP’s jailed former leader, Selahattin Demirtaş, has signalled that his first choice would be the “inclusive” İmamoğlu.

Waiting game

Whether or not Kılıçdaroğlu ends up being the one to face Erdoğan, he will be critical to the opposition’s efforts to navigate the choppy waters ahead. “He is the one keeping all guys at the table together, says Ayşe Çavdar, an anthropologist who has spent decades researching religious conservatives in Turkey. Kılıçdaroğlu could win, she believes, if İmamoğlu offers his “very strong” public backing.

İmamoğlu, a CHP member, has repeatedly doffed his cap to the party leader in recent weeks, while also saying he trusts the six opposition leaders to make “the right decision” on the candidate.

Yet for now, the opposition has sought to delay the process. Özer Sencar, head of the polling agency Metropoll, worries that it is wasting precious time. Erdoğan could yet decide to call a snap election in the autumn, he says, if the president thinks conditions are favourable enough or that he can mitigate them, perhaps with a slew of populist giveaways such as a fresh increase to the minimum wage.

If so, he warns, the opposition will have left it very late to begin the huge task of getting a campaign up and running and, in particular, putting together an economic programme that convinces the public that they can fix the economy — something polling suggests they have so far failed to do.

Kılıçdaroğlu’s detractors suspect him of delaying on purpose in the hope that he will narrow the polling gap with his rivals. They accuse him of surrounding himself with loyalists who lack the guts to confront him with the truth that he is too risky a choice to be the campaign’s frontman. The danger, they say, is that Kılıçdaroğlu and his allies make a historic miscalculation by insisting that he should be the candidate.

That view is rejected by Fethi Açıkel, a member of the CHP executive committee who insists his party chair fully grasps what is at stake. “Of course he is the natural candidate for us and will not shy away if nominated,” he says. “But don’t forget that, in past elections, he has allowed others to run instead of him. He is both very strategic and very humble. He knows we need to win.”

Like many of Kılıçdaroğlu’s supporters, Açıkel argues the party leader “deserves” the candidacy in recognition of the work he has done for Turkish democracy in recent years.

But if he is to break Erdoğan’s grip on Turkish politics, critics say that is simply not enough. “He deserves it, it’s true,” says Sencar, the pollster. “But is it more important to be the candidate, or to win?”

Additional reporting by Funja Guler