By Jean Mackenzie, Reporting from Odesa, Ukraine

Sakelari Photo

Sakelari PhotoDark storm clouds threatened to upend Serhiy and Tania’s beach wedding. But as the couple walked down the long white staircase to greet their guests, the empty chairs signalled there was a bigger problem. In total, half of their guests were missing.

Their family and friends sent their apologies but explained that the risk of attending had been too great. What if they had been caught by one of the conscription squads, which now roam Ukraine’s streets?

With many of its soldiers dead, injured or exhausted, the Ukrainian government has stepped up its efforts to mobilise more men.

A new law, introduced in May, requires every man aged between 25 and 60 to log their details on an electronic database so they can be called up. Conscription officers are on the hunt for those avoiding the register, pushing more men who do not want to serve into hiding.

Family handout

Family handoutOverlooking the Black Sea in the southern city of Odesa, Tania quietly murmured that she understood why her friends and family did not want to fight.

Her father was killed on the front line in October, during the attritional battle for Avdiivka, and the 24-year-old is now terrified of her new husband being conscripted. “I don’t want this to happen to my family twice,” she said.

More than two years into the war, almost everyone knows someone who has been killed. Grim news has poured out from the front, of Ukraine being vastly outnumbered and outgunned.

Over the phone, the couple’s friend of 15 years, Maksym, relayed such tales. Among the dead are around a dozen of his friends and acquaintances. “There are more than a million police officers in Ukraine, why should I fight when they are not?” he said.

Maksym, who has a young daughter and wife who is seven months pregnant, said he was sorry to miss the wedding but was afraid of being “grabbed” by conscription officers who he likened to “bandits”.

Thanyarat Doksone/BBC

Thanyarat Doksone/BBCThe mobilisation squads have a fearsome reputation, especially in Odesa, for pulling people off buses and from train stations and ferrying them straight to enlistment centres.

For those avoiding the draft, public transport is now off limits. So too are restaurants, supermarkets, and weekend trips to the park to play football.

“I feel like I am in a prison,” Maksym said.

On a Tuesday morning, a dozen conscription officers descended on Odesa’s main train station, led by a seasoned veteran sailor, Anatoliy, and his younger, more muscular counterpart Oleksiy. They paced the forecourt, stopping men of serving age, to check they were registered on the database.

But the well-mannered pair had a tough time finding eligible men. Most were either too young or had received some sort of exemption. After a couple of hours Anatoliy conceded that it was highly possible men were hiding from them.

“Some people run away from us. This happens quite often,” he said. “Others react quite aggressively. I don’t think these people have been brought up well.”

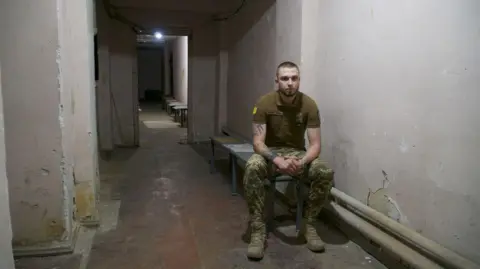

Thanyarat Doksone/BBC

Thanyarat Doksone/BBCAt the enlistment centre around the corner, an optimistic note taped to the door notified would-be-recruits that those who had come voluntarily could skip the queues. But there were no queues. A lone man sat waiting to be seen.

When I asked whether he was there out of choice, he told me he had been “kidnapped” that morning and brought against his will.

“The officers encircled me so I couldn’t run,” he stuttered in shock. “I’m devastated.”

One of the officers at the centre, Vlad, conceded that there were barely any willing volunteers these days. Under the call sign Hora, Vlad fought in some of the fiercest battles along the eastern front line in the Donbas before being struck in the head, chest, and legs by artillery shrapnel.

He was unable to mask his contempt for those who are hiding. “How can I say this without swearing?” he asked out loud.

“I don’t consider them men. What are they waiting for? If we run out of men, the enemy will come to their homes, rape their women, and kill their children.” Vlad has seen the awful evidence first-hand.

Thanyarat Doksone/BBC

Thanyarat Doksone/BBCThis latest conscription drive has opened up uncomfortable divisions in society, not only between those serving and those avoiding the draft, but also between female friends, some of whom have partners on the front line, and others who are hiding their boyfriends at home.

The topic of mobilisation creeps into almost every conversation, which then often turn heated. Last month someone threw an explosive into the garden of an enlistment officer’s home.

There is a striking distrust among the men choosing not to enlist. They do not trust the officers, after some were found to be taking bribes to help men escape the country. Nor do they trust they would be adequately trained.

Marek Polaszewski

Marek PolaszewskiOn the outskirts of Odesa, Vova appeared sheepishly at the door of his apartment block, using his seven-year-old daughter as a shield. The IT engineer will not leave the house without her as he knows the officers cannot snatch him if they are together.

Last year, while on his way to work, he was ordered off a bus by the military at gun point, he said, and taken to an enlistment centre. He convinced the officers to let him go to fetch some documents, but vowed to himself he would never return.

“I’m not a military man, I’ve never held a weapon, I don’t think I can be useful on the front line,” he said.

He then reeled off the same list of reasons given by every draft dodger we spoke to – a family to support, some minor medical ailment, and a defiant declaration he was sending humanitarian aid to soldiers.

But underneath these excuses is always the same fear, that within weeks of registering, these men would end up as cannon fodder on the front line that, to their eyes, does not appear to be moving. This is despite recent attempts by the government to give recruits some say over which units and roles they are assigned to.

When speaking to these men, there is somewhat of a disconnect. They are holding out for a Ukrainian victory, just one that does not involve them.

“I am proud that many men made the brave decision to go to the front line,” said Vova. “They are truly the best of our country.”

Thanyarat Doksone/BBC

Thanyarat Doksone/BBCAt a conscript training camp in a forest outside Kyiv, its leader Hennadiy Sintsov breathed heavy sighs, as he supervised men with shovels digging foxholes.

“It might look like banal work, but this is as important as being able to fire artillery,” he said. “It could save their lives”.

Mr Sintsov, a patriotic volunteer with revolutionary spirit, oversees the mandatory 34-day training programme all conscripts must complete before being despatched to their military units. He stressed repeatedly that these men would not be sent to the front line straight away, and that further training would follow.

On a break from training, Sintsov’s cohort of conscripts sat smoking and joking. They were a rag-tag group mostly in their late 40s and 50s – a pig breeder, a warehouse manager, and a builder – who admitted they would rather not be there. But nor did these men want to spend the rest of the war in hiding.

One of them, Oleksandr, had already opted to become a drone pilot. “I’m pretty scared, this is all new to me, but I have to do it,” he said.

But the 33-year-old tram engineer did not judge those choosing to hide. “I’ve made my choice, they can make theirs,” he shrugged.

Sinsov was troubled by how unmotivated his new arrivals were. Despite the daily reminders of war – the air raid sirens and rolling power cuts – he believes the threat of war has grown too distant for those living in the relative safety of cities such as Odesa and Kyiv, and fears it will take another major Russian advance to spur Ukraine’s draft dodgers into action.

“Then we would see people searching for guns and queuing at enlistment centres again,” he said.

Additional reporting by Thanyarat Doksone and Anastasiia Levchenko