A combination of supply chain chaos, higher costs and concerns about working conditions is forcing some western fashion brands to rethink their decades-old dependence on factories in China.

Dieter Holzer, the former chief executive and a board member of Marc O’Polo, said the Swedish-German fashion brand started to swap some suppliers in the country in favour of factories in Turkey and Portugal in 2021.

The decision was meant to “balance and take out risk from your supply chain and make it more sustainable”, he said. “I think many companies across the industry are reviewing their exposure [to China].”

The shift away from mass textile production in the country, albeit still in its early stages, marks the reversal of years of outsourcing to a region that has come to dominate the textile supply chain.

Big names such as Mango and Dr Martens have recently cut or signalled their intention to shift manufacturing out of China or south-east Asia.

“The big message is reducing reliance on China,” Dr Martens’ chief executive Kenny Wilson said in November. “You don’t want all of your eggs in one basket.”

The bootmaker has moved 55 per cent of its total production out of the country since he took over in 2018. Just 12 per cent of its production for the 2022 autumn/winter collection was manufactured in China compared with 27 per cent in 2020 and it estimated this will drop to 5 per cent this year.

“We are being deafened by the sound of clothes manufacturers [moving] away from Asia,” said Rosey Hurst, director of ethical business consultancy Impactt.

The relocation was also being driven by stricter laws being introduced in the US and Europe against labour abuses, she added, following the alleged use of forced labour in the cotton-rich territory of Xinjiang in China.

Mango’s chief executive Toni Ruiz said in December he was considering buying less from China “but we’ll be very alert to how things evolve”.

“What we’re looking at is the extent to which all this global sourcing, developed over many years, might become more local,” he said.

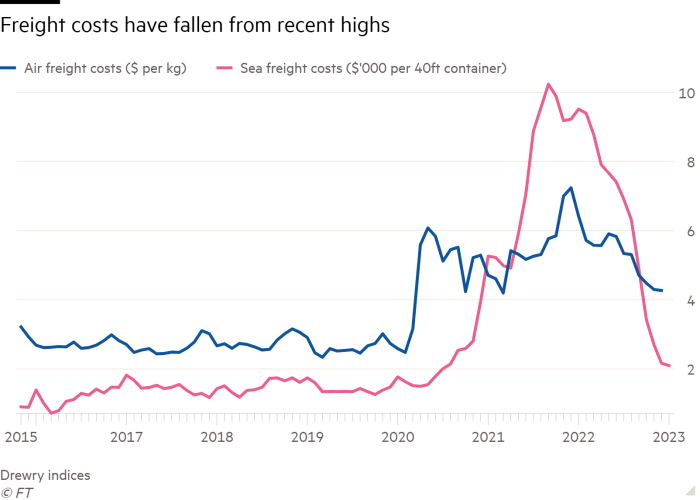

The shift was accelerated by continued supply chain disruption since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to a jump in freight costs, as well as significant shipping delays as factory workers at manufacturing hubs across Asia fell ill or were forced to isolate.

One industry consultant said that one retail client’s ski wear, from a previous season, arrived in the summer of 2022.

“For many, gone are the days of manufacturing only in China and shipping everywhere,” said Todd Simms, vice-president at supply chain intelligence platform FourKites.

“Disruptions have increased costs to deliver finished goods, making it easier to justify operations in new countries in exchange for more resilience,” he added.

The financial incentives to remain in the region are diminishing as wages go up after years of cheap labour — a major draw for many household names to outsource manufacturing to far-flung places.

According to statistics from China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the average factory wage doubled between 2013 and 2021, from Rmb46,000 ($6,689) per year to Rmb92,000.

Jose Calamonte, chief executive of online fashion retailer Asos, told investors at the company’s full-year results presentation last year that products manufactured in China were not as competitive as they seemed relative to Europe, once shipping and transport costs were taken into account.

“We try to think about the final [profit] margin once we’ve made the final sale,” he said.

European clothing retailers’ efforts to cut delivery times, as fashion trends and consumer needs change quickly, is another reason behind their decision to opt for suppliers closer to home.

“We’ve been taking control of our manufacturing,” said a spokesman for a British luxury brand, adding that the industry has been consolidating in Europe for years now. “This has been a trend for reasons to do with speed and efficiency.”

Plans to shift production away from Asian garment hubs, however, are not that advanced owing to their complexity. Countries such as China and Vietnam represent the lion’s share of textile exports, according to 2020 data from CEPII.

For example, more than half of suppliers to Inditex, the world’s largest fashion retailer, were based in Asia in 2021, only a marginal reduction on 2018.

Turkey has been positioning itself as a winner from western brands moving their production, not least because it is part of the EU customs union, allowing frictionless trade between member states.

“It is a popular destination and already used by the likes of Hugo Boss, Adidas, Nike, Zara,” said Simon Geale, executive vice-president of procurement at supply chain consultancy Proxima.

An increasingly important consideration for retailers is traceability in the supply chain after years of widely reported labour abuses.

“[Because of US laws against cotton from Xinjiang], brands have to have much better traceability, ” said Impactt’s Hurst.

“Then we have got European laws [on forced labour] coming up. It is putting pressure on the industry to get a grip,” she said.

But she warned: “There isn’t enough money in [international supply chains] to run things the way they should be done. [Given the current economic crisis], that is only going to get worse.”

Maximilian Albrecht, an analyst at AlixPartners, said that many fast fashion labels were also abandoning China in order to differentiate themselves from Shein, the rapidly growing Chinese fast fashion giant.

“European brands can’t match Shein on their costs of production, their network of production, their relationships,” Albrecht said.

“I think you’ll see some brands say ‘well, we can’t match that so we’ll move to Europe’. You can still sell the story that they have higher quality products. Whether that’s actually true is another thing.”