This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. We have been pessimistic about China. But not pessimistic enough, as you will see below. We are taking tomorrow off as Rob flies to London and Ethan works on non-Unhedged projects. We’re back with you Thursday. Email us: [email protected] and [email protected].

China growth: worse

The last time we wrote about China, at the end of last month, the topic was the country’s “impossible trilemma”. Solving simultaneously for 5.5 per cent economic growth, a stable debt-to-GDP ratio, and zero Covid-19 is impossible. Given this, the short-term path of least political resistance for Beijing is supporting growth by pouring debt into low-productivity real estate/infrastructure projects. Recent noises from Xi Jinping make it clear that the country plans to take the easy path again.

But it turns out that describing the situation as a trilemma is too generous. Horrific economic data from China in April suggests that the zero-Covid policy may be inconsistent with anything but meagre growth, even in the presence of government attempts at stimulus.

Here is what April looked like in China:

-

Retail sales down 11 per cent from a year earlier, against an expected decline of less than 7 per cent.

-

Industrial production dropped 2.9 per cent.

-

Manufacturing was particularly weak, with auto production falling 41 per cent.

-

Export growth was 4 per cent, a screeching slowdown from 15 per cent growth in March.

-

Real estate activity collapsed, with construction starts falling 44 (!) per cent

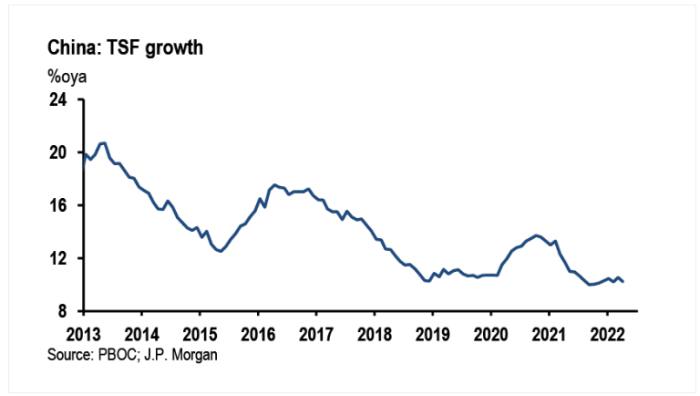

The backdrop for all this is credit growth that stubbornly refuses to accelerate, despite policy tweaks (such as last months reduction of banks’ reserve requirements) and jawboning from the authorities. Here is a JPMorgan chart of total social financing (TSF) — a broad government measure of credit creation — through April:

JPMorgan’s Haibin Zhu breaks the sideways pattern into three pieces:

(1) contraction in household loans, as industry data suggest further deceleration in property sales; (2) notable slowing in medium to long-term loans to the corporate sector, reflecting weak credit demand for corporate sector financing and investment; (3) moderation in government bond issuance.

Number 1 speaks for itself. China’s real estate industry is undergoing a wholesale restructuring. Homebuyers are going to be treading carefully.

As for number 2, the key word is “demand”. Why would a corporation want to risk a big new investment, even if bank financing were available, when the zero-Covid policy has an estimated 300mn city dwellers under some form of lockdown. How do we know it’s a demand issue? Zhu noted “the discrepancy between pick up in M2 [broad money] growth . . . and slowdown in loan growth . . . Accordingly, the ratio of new loans to new deposits fell to 86.2 per cent.” That’s the lowest ratio in five years.

And so we turn to government bond issuance, the go-to when the government wants to create some growth. But there is a nasty problem there as well, as my colleagues Sun Yu and Tom Mitchell pointed out in an outstanding feature last week. Local government financing vehicles, a crucial funding conduit for infrastructure projects, are facing constricted access to bank credit:

Bond issuance by LGFVs was just Rmb758bn ($112bn) over the first four months of this year, down almost 25 per cent from the same period in 2021. Many Chinese banks now prefer to lend to infrastructure projects led by large state-owned enterprises rather than LGFVs, which they see as too risky.

The government will probably keep trying to jump-start things. Over the weekend, for example, the mortgage rate for first-time buyers was cut. But whereas a few months ago brokers and pundits held out hope for a fillip from government action, there is now increasing pessimism about how much in can help while the lockdowns are in place. Gavekal Dragonomics noted there is “a fundamental tension between maintaining the current Covid prevention strategy and lifting growth”, which renders fiscal stimulus increasingly impotent — as demonstrated by low infrastructure investment in April.

This quote from the FT understates the point nicely:

Zhiwei Zhang, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management, noted that the government was under pressure to launch new stimulus measures and that the mortgage rate cut was “one step in that direction”. But he added that “the effectiveness of these policies depends on how the government will ‘fine-tune’ the zero-tolerance policy against the Omicron crisis”.

Fine-tune! People don’t buy new houses when they are locked in their old ones, and businesses don’t borrow when supply chains are shut down. Will the government relent on zero Covid? No one seems to think so. Here is the spectacularly depressing sign-off quote from Yu and Mitchell’s piece:

Few expect Xi to relax his zero-Covid campaign before securing an unprecedented third term in power at a party congress later this year. The strategy “has become a political crusade — a political tool to test the loyalty of officials”, says Henry Gao, a China expert at Singapore Management University. “That’s far more important to Xi than a few more digits of GDP growth.”

Both equity and credit markets in China capture this grim reality:

Still, one way or another, sooner or later, the lockdowns will end. And there are some signs that the current wave of infections could be subsiding. Bloomberg reported on Sunday that total cases in Shanghai were falling, and that no new cases had been reported outside of the city’s quarantine areas in two days — nearing a key threshold from relaxing lockdown protocols.

This sort of thing is enough to bring out the optimists. JPMorgan’s China equity strategy team has rolled out a list of stocks that will “benefit [from] the Shanghai reopening theme”. They include transport, semiconductor, auto parts, and building materials companies. Looking at the price chart above, it is pretty clear that whoever times the reopening trade just right is going to make some money in these sorts of names. We wish them well, but wouldn’t know how to time it ourselves.

What kind of growth rate China’s economy returns to is a separate question. Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics argued the key variables will be global demand and the desire of the government to stimulate after the lockdowns are lifted. He foresees a recovery that begins quite soon, but wrote that:

This recovery is likely to be more tepid than the rebound from the initial outbreak in 2020. Back then, Chinese exporters benefited from a surge in demand for electronics and consumer goods. In contrast, the pandemic-induced shift in spending patterns is now reversing, weighing on demand for Chinese exports. Meanwhile, officials are taking a more restrained approach to policy support this time . . . The upshot is that while the worst is hopefully over, we think China’s economy will struggle to return to its pre-pandemic trend.

We agree with Evans-Pritchard about global demand but disagree about government restraint. Our guess — and that’s the only word for it, admittedly — is that the futility of stimulus under lockdown will only increase the political imperative for fiscal and monetary largesse after lockdowns end.

One good read

Depressing example of how capitalism works: the e-pimps of OnlyFans.