Jesika Gonzalez will tell you that she wasn’t the biggest fan of Porterville, California while she was growing up.

“When I was younger, I was very, like, angsty,” the 18-year-old said as she flicked her purple hair over her shoulder. “Whatever, this town’s small, nothing to do.”

Porterville is a predominantly Hispanic working-class town in the Central Valley of California, where environmental hazards include some of the worst air quality in the state; the past year’s torrential rains that inundated hundreds of acres of farmland; and a heat wave that pushed temperatures past 110 degrees Fahrenheit this July.

But Porterville has this going for it: Its school district pioneered a partnership with Climate Action Pathways for Schools, or CAPS, a non-profit organization that aims to help high school students become more environmentally aware while simultaneously lowering their school’s carbon footprint and earning wages.

CAPS is part of a growing trend. Like similar programs in Kansas City, Illinois, Maine, Mississippi, and New York City, CAPS is using the career-technical education, or CTE, model to prepare young people for the green jobs of the future before they get out of high school.

For Gonzalez, a self-described tree-hugger, the program has changed the way she looks at her hometown. These days, she downright appreciates it “because I’ve had the opportunity to see that sustainability is everywhere.”

CAPS started in part because a local solar engineer, Bill Kelly, wanted to share his expertise with students in the school district’s career-technical education program. Kirk Anne Taylor, who has a deep background in education and nonprofit management, joined last year as executive director with a vision to expand the model across the state, and far beyond just solar power.

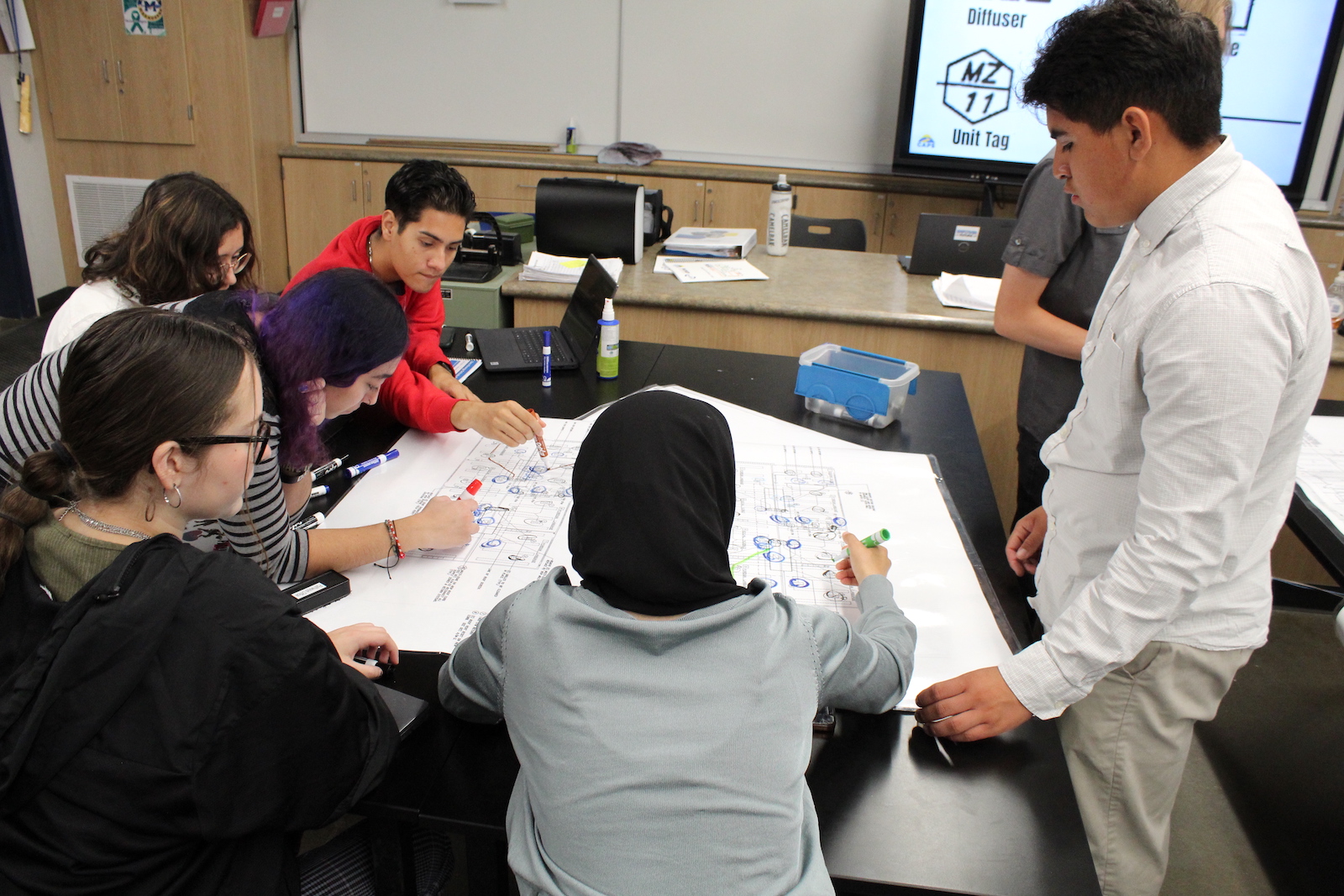

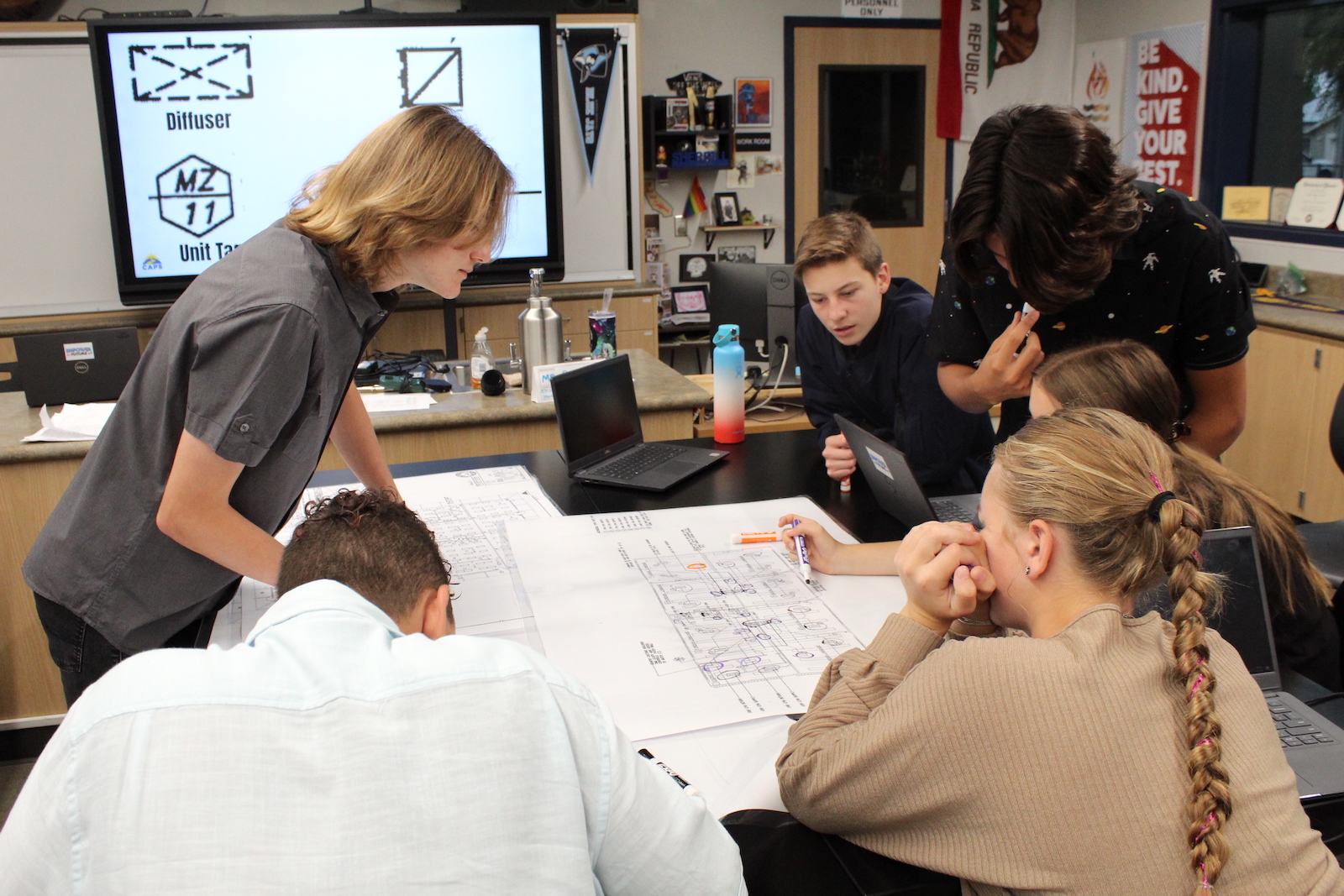

CAPS students are trained for school-year and summer internships that teach them about the environment and how to lower the carbon footprint in school buildings and the larger community. They earn California’s minimum wage, $15.50 an hour.

For instance, Gonzalez and her classmates held a bike rodeo for younger students. They’ve created detailed maps of traffic and sidewalk hazards around schools, to promote more students walking and biking to schools.

Other CAPS participants give presentations, educating fellow students about climate change and green jobs. They are helping manage routes and charging schedules for the school’s growing fleet of electric buses. They work with farmers to get local food in the cafeterias.

Their most specialized and skilled task is completing detailed energy audits of each building in the district and continuously monitoring performance. In the first year of the program, some of these young energy detectives discovered a freezer in a high school holding a single leftover popsicle. Powering this one freezer over the summer vacation meant about $300 in wasted energy costs, so they got permission to pull the plug.

Climate Action Pathways for Schools

The popsicles add up. Over the past few years, by reviewing original building blueprints, inputting data into endless Excel spreadsheets, and cajoling their classmates and teachers into schoolwide efficiency competitions, CAPS students have saved the district $850,000 on a $2.9 million energy budget — this in a district that was already getting about two-thirds of its energy from onsite solar. And 100 percent of the most recent participants are going on to college, far higher than the students who aren’t in the district’s career-technical education program.

CAPS is small, just 18 students this year. But its model sits right at the intersection of several big problems and opportunities facing the country. One is that in the wake of the pandemic, public school achievement, attendance, and college enrollment are all suffering, especially in working-class districts like Porterville. This is likely not entirely unconnected to the fact that young people are suffering a well-publicized mental health crisis, of which eco-anxiety is one part.

Career technical education programs like this one have been shown to lead to higher graduation rates and to put more students, especially working-class students, into good jobs.

And there’s massive demand for green workers in particular: Skilled tradespeople like electricians are already in short supply, making it difficult for homeowners and businesses to install clean energy technologies. The Inflation Reduction Act and associated investments are expected to create 9 million new green jobs over the next decade.

Some CAPS students are also changing community attitudes toward climate change, starting with their own families.

Gonzalez says her dad is skeptical of climate change and the progressive politics it’s associated with, while her mom seems passive — “like, what can I do?” But they supported her involvement in CAPS because it’s a paying job, and recently her dad said, “I’m proud of you for doing what you like to do.”

She’s heading to California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt in the fall to study environmental science and management.

Climate Action Pathways for Schools

David Proctor, 17, grew up the oldest of seven. His mother didn’t believe in climate change, Proctor says, but grudgingly agreed to the CAPS program. It helps that Proctor is earning money for his work monitoring the district’s solar performance. He loves every minute.

He’s on track to graduate this coming December and be the first in his family to go on to college. He wants to combine his interest in climate change and public health.

Jocelyn Gee is the head of community growth for the Green Jobs Board, which has a reach of 96,000 people and focuses on creating equitable access to high-quality green jobs. They see a huge demand for programs like CAPS.

“We get a lot of requests from college students and high school students about what kind of roles are there for them,” Gee said. “This field hasn’t existed for that long. There are very few people. So you need to invest in training the next generation now so a few years on you will have the brightest in the climate movement.”

They said the strength of a program like CAPS is that it’s making life better for Porterville residents right now. “I really think that hyperlocal solutions are the way to go,” Gee said. “It’s great when green jobs involve the frontline communities in solutions.”

One factor that distinguishes CAPS from other green CTE programs is that it’s also designed to address the opportunity for public schools themselves to decarbonize. Schools collectively have 100,000 publicly owned buildings, and energy costs are typically the second largest line item in budgets after salaries. The Inflation Reduction Act, along with Biden’s infrastructure bill, contains billions of dollars intended specifically to address school decarbonization, but many districts lack the grant-writing and other expertise required to chip the money loose.

In partnership with CAPS, the Porterville Unified School District, or PUSD, recently learned they’ll be bringing in $5.8 million over three years from the federal Renew America’s Schools grant program. The money will fund lighting, HVAC and building automation upgrades–all needs identified by the students’ energy audits — as well as an expansion of the internship program itself. Only 24 grants were awarded nationwide out of more than 1000 applications, and the education component made Porterville’s stand out. PUSD and CAPS have also scored a $3.6 million grant from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) for a green schoolyards program.

The district is also applying for an Environmental Protection Agency grant that would allow them to go from six electric school buses to 41, nearly the entire fleet. The vision is to train students to maintain and repair these as well. CAPS students have already started analyzing and planning more energy-efficient routes that allow for charging.

“The issues we’re trying to address are common, and we’re delivering real benefits: environmentally, in terms of student outcomes, in terms of cost savings,” says Kirk Anne Taylor, CAPS‘ executive director. CAPS is expanding to three other districts in California, with more in the works, and the program in Porterville has drawn visitors from Oregon, New Mexico, and as far away as Missouri.

For Elijah Garcia, a graduating senior headed to the University of California,San Diego to study chemical engineering, the work has given him a newfound commitment to pursuing a sustainable career. It’s also given him hope for the future.

“We’re trying to change something — climate change — that when you look at it in a vacuum it’s, like, insurmountable. But this is boots on the ground. It’s a bit more tangible. I can’t do everything, but I can do this little bit.”