December 22, 2022

From the Winter 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Though they breed where the treeline gives way to tundra in northern Canada and Alaska, American Tree Sparrows visit backyards, farmlands, and open woodlands across southern Canada and the north-central United States in winter. Small flocks converge on snow-swept fields and beneath bird feeders, trading soft, musical twitters as they feast on seeds on the ground. Sometimes they’ll perch on the tops of bent grasses that poke through the snow and beat their wings to dislodge seeds from the grass head.

- Contrary to their name, American Tree Sparrows usually forage and nest on the ground. European settlers gave this species a misleading name because it reminded them of Eurasian Tree Sparrows back home.

- A day of fasting is usually a death sentence for the American Tree Sparrow, which needs to take in about 30% of its body weight in food and a similar percentage in water each day to maintain body temperature and weight at healthy levels.

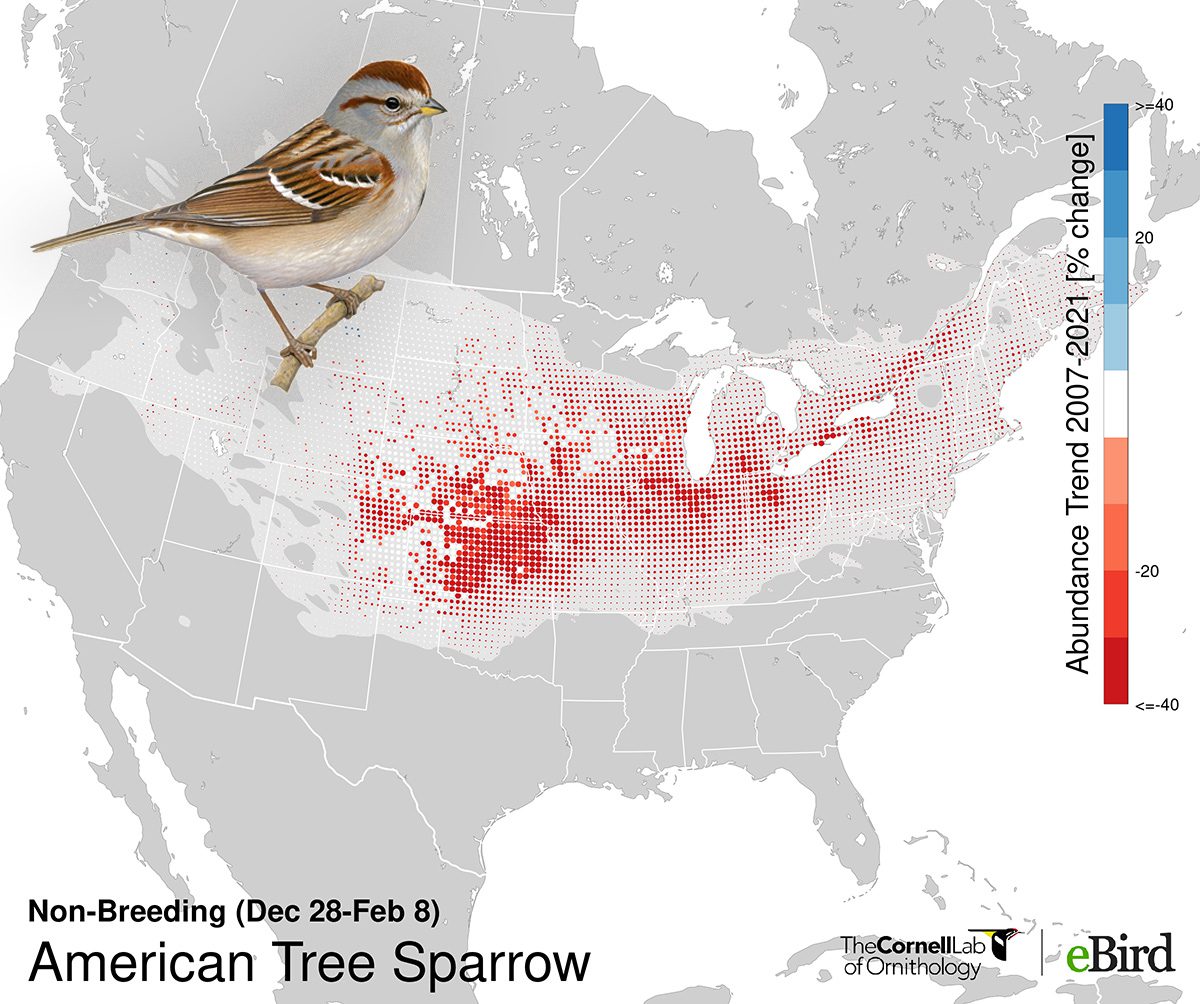

- According to eBird Status and Trends data, Kansas and Nebraska host the most American Tree Sparrows from December to February, with 18% and 15%, respectively, of the global population overwintering in those two states.

- American Tree Sparrows look similar to Chipping Sparrows, but in many areas they arrive on their wintering grounds just as Chipping Sparrows are heading farther south. Thus the two species rarely occur at the same place and time.

Find This Bird: In winter, watch beneath bird feeders for plump and long-tailed sparrows scratching and pecking for seeds on the ground. American Tree Sparrows have a bicolored bill and central breast spot, which helps them stand out from other sparrows.

Insights from eBird Trends

eBird Trends shows that American Tree Sparrow populations are declining across much of their wintering range, with some areas of increase in Montana. “The maps don’t tell us why,” says eBird data scientist Tom Auer, “but agricultural intensification and pesticide use in the core of their range could be factors in the declines. At the same time, climate change might allow the species to winter farther north.”