As I drive through the Rhondda Valley in south Wales for this Lunch with the FT, I reflect that it is hard to imagine anywhere in the UK further removed from the highly charged City environment where my guest recently hit the headlines. Amanda Blanc, the boss of British insurer Aviva, this month became a social media sensation after calling out the casual sexism of some of her investors at the annual shareholder meeting.

Now, she has invited me back to her hometown. I accepted readily, never needing an excuse to return to enjoy the lush countryside of the south Wales valleys where I grew up.

My approach to Treorchy involves a drive over the majestic Bwlch hillside — dodging sheep that spill into the road — and then a sweeping dip down into this former coal-mining town. We are to meet at the unpretentious-sounding Cwm Farm Shop. I have visions of a converted stone barn. But the satnav takes me into the town centre, awash with schoolchildren queueing for fast food, then off to an industrial estate: there’s a tyre shop, a clothing factory, a carpet warehouse.

Surely this can’t be right. After a quick stop for directions, I learn that I am indeed in the correct place. Around the back of the giant tin warehouse, next to a distributor of industrial valves, is our venue. The Farm Shop has prettified its corrugated-metal exterior with wooden cladding and an array of outside tables. I venture inside, and through a shop filled with cuts of meat, fresh bread and farm produce, to find Blanc sipping a pre-lunch coffee.

So why here, I ask, as I scan the burgers and all-day breakfasts on the menu. It’s just the nearest place to her parents’ house, a couple of miles up the road, she explains. To be fair, I’d been the one to suggest that we lunch in the area — but I can’t think of many FTSE 100 bosses who would choose the Cwm Farm Shop when there’s a Michelin-starred option 20-odd miles away — and the FT is paying.

Blanc is one of only nine female FTSE 100 chiefs. Her success in restoring the fortunes of one of Europe’s biggest insurers is legendary. She is among the City’s most influential and authoritative figures, which is all the more striking given her upbringing. She grew up in a former mining heartland, with two miners for grandfathers, amid a veneration for chapel Sunday school and a visceral love of community. She was a teenager in the 1980s when then prime minister Margaret Thatcher declared war on the mining industry — including the south Wales valleys.

“That was incredibly difficult. People would be knocking on the door asking for food, donations for food, the community came together. But it broke this [place]. At one point in this area there must have been seven or eight mines. It was the industry, and then all the other businesses sprang up from that — the pubs, the railways, the food places, the high street. You could argue that there’s never been a recovery, not here.” (Treorchy suffered a second blow in 2007, when Burberry, another anchor employer, moved production to China from the very warehouse where we’re lunching.)

Environmentally, in retrospect, curtailing British mining was the right thing to do, Blanc says. But the approach was the problem — “the brutality of the way it was done, and what it did to the community. That was more the lasting impact.” Billy Elliot, the blockbuster film and musical, has long been a favourite, she says: the tale of the young ballet dancer who escapes the hopelessness of a scarred mining community in the north-east of England “really resonates”.

Blanc’s escape was very different. A lot of the people I knew, growing up in the area at that time, were politicised by the miners’ battle for survival in the face of Thatcher’s reforms. Many became life-long Labour supporters, some fervent anti-capitalists. And yet Blanc has ended up at the heart of the capitalist system. I ask how that happened.

She pauses for thought, thanks to the arrival of our burgers, generous portions artfully arranged with relish on open buns — avocado on mine, creamy coleslaw on Blanc’s. It wasn’t about being for or against capitalism, she says. “I don’t think I was intellectually thinking about it that way. But I think going into insurance — whilst, of course, insurance is capitalist, because it’s a big business and it makes big profits, sometimes — it is something which actually keeps people safe.” In someone less grounded, this might sound like blather. But Blanc just about pulls off the vocational argument. “You are protecting something that really matters to somebody. You’re helping them to go about their day-to-day life.”

She recalls one of the first big claims events she had to deal with, as a young insurer, after the storms of 1991. “You were basically taking calls from people whose houses had been really badly damaged. And then you thought, oh, actually, there’s a really good thing about this. You’re doing something really good here.”

I’ve been making Blanc talk so much that she’s making slow progress with her burger, though the chips (“proper chip-shop chips”) have been polished off, as have mine. My falafel burger is beautifully moist and the jackfruit sauce delivers a sweet kick, offset by the avocado relish.

With modest pride Blanc tells me how her career in insurance — long one of the most male-dominated of any sector — progressed quickly. Aged 29, she became Commercial Union’s youngest ever branch manager. And working for a succession of male managers, whose support she extols, she rose through the ranks of CU (now Aviva), Axa, Groupama and back to Aviva. Only her interlude at Zurich, from 2018 to 2019, was an unhappy one. Things didn’t click with chief executive Mario Greco: she is tight-lipped about the reasons why but insists it was the right call to quit after only eight months. (“It didn’t work. We were just not aligned.”) There was a brief stint as a portfolio-career board member of multiple companies, when suddenly she was tapped for the top job at Aviva.

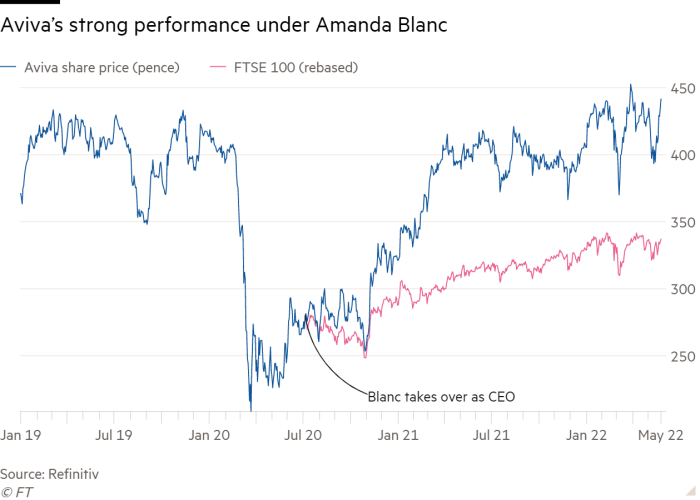

Her two immediate predecessors had proved increasingly irritating to shareholders, with the stock price halving in the three years before she took over. One had lost focus on the core business and got carried away with a “digital garage strategy” (another “misalignment”, says Blanc); the next had thought he could get away with a business-as-usual approach —“carry on doing things, but doing them a bit better. And I think quite a lot of the investors were like, ‘uh, no’.”

Blanc did not hang about: within a few months she had sold a string of foreign subsidiaries and returned capital to shareholders — spurred to go further and faster by Cevian, the Swedish activist that is now the company’s second-biggest shareholder after buying a 5 per cent stake a year ago. Is it annoying having an activist on your shoulder? “Not at all,” she says, arguing their agendas are aligned. So there are no points of tension? “Some of their numbers are different to ours because it’s my job to make sure that we have a sustainable distribution of dividend, not one which gives a quick injection over the next three years and then the company’s left with no money for investment over the future.”

Either way, the formula has worked. Aviva’s shares have jumped almost 60 per cent under Blanc’s leadership, recovering from a dip after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

I ask her how bad she thinks the economic shock will turn out to be. She cites the Aviva house view, warning of unemployment and potential stagflation if inflation reaches 10 per cent this year. “That’s when things start to get pretty difficult. So, low growth, high interest rates. That’s not a good place to be” — particularly for consumers.

So where does she stand on the debate over the windfall tax on energy companies to help fund assistance for stretched households?

“I don’t really have a set view on it. But I think you’ve got to do something more sustainable. That would be my view. Does a one-off injection really, really help? And it [is] very anti-Conservative.”

Our waitress hovers. Blanc says that, yes, despite the untouched bun and the mound of coleslaw, she’s finished. To my delight, though, she declares with a grin: “They’ve got some cakes.” We traipse to the shop area and discover a fridge full of old-fashioned fresh-cream favourites: eclairs, millefeuilles, fruit tarts. I opt for the eclair, which gapes open with a vast drift of piped cream. Blanc’s eye is caught by the ice-cream fridge. She asks if it’s local. “Gelli,” comes the reply. “What, Johnnies?” she asks excitedly. It is — and I’m treated to a few minutes’ reminiscence about childhood summers in the Rhondda, seaside trips to Porthcawl and Tenby, and the relative merits of their special confections.

Enough reminiscing. Knowing that one of her bugbears is the extent to which the promised relaxation of restrictive European insurance regulation — so-called Solvency II rules — has yet to materialise, I ask why she cares so much. The mixed messages from government and regulators mean that a key policy priority — investing in UK infrastructure — remains hamstrung, she says, despite being a core part of the plan to “level up” the country. (“Wouldn’t it be ironic,” she says, “if post-Brexit we actually were in a worse situation than Europe?”)

The insurance industry has “significant amounts of money to invest”, if only it were freed up to spend it. “There are big projects around science parks and the university infrastructure, and with that comes a campus, with that comes a hospital, with that comes a school, with that comes all those sorts of things — wind farms, climate transition businesses — so invest in technology companies that are looking at the transition.” She pauses for breath. “Why wouldn’t we be allowed to do that?”

The government often talks about levelling up between the north and south of England, I say. Does this annoy her? “It definitely can’t be a north-south thing because we know that there are equally poverty-stricken areas in the south of England, in Wales, in other places, other than just in Teesside or other areas where I know the government has focused attention.”

It’s as if I’ve pressed all Blanc’s buttons at once — she’s advocating for disenfranchised communities such as the Rhondda, for the benefits of infrastructure investment, for the commercial opportunity. “You can’t have everybody, all the scientists, all the support workers for the scientists, all in one part of the country. It’s bonkers. You’re basically saying there’s no clever people in Cardiff, in Newcastle.”

The levelling-up agenda should cut the other way too, Blanc says. As was true 30 years ago in her case, and remains true today, there are no mechanisms in financial capitals such as London to do proactive outreach to hire from the regions. “There’s nobody pulling you in. It’s you forcing yourself in and thinking, actually, I’m OK here.”

If regional and social diversity are still lacking for blue-chip employers, the same goes for gender diversity, especially at senior levels, with a vicious-circle effect, says Blanc. “If you don’t see lots of female FTSE CEOs, then nobody’s going to assume that you should be a female FTSE CEO. They’re going to assume that every FTSE CEO needs to look a certain way.”

Cwm Farm Shop

Treorchy Business Park, Treorchy CF42 6DL

Burger £7.50

Falafel burger £6.50

Chips x2 £4.40

Side salad £2

Juice £1.95

Lemonade £1.50

Latte £2.90

Diet Coke £1.50

Americano x2 £4.40

Total £32.65

As Blanc tucks into her vanilla ice — the palest yellow and “so good” — we have finally come to the topic that has thrust her into the limelight in recent weeks: the sexist sniping at her leadership during the company’s AGM, and her response to it.

First, the criticisms. One small shareholder stood up and said Blanc was “not the man for the job”. Another snidely praised Blanc and the other women on the board for their skills at “basic housekeeping activities”. A third said she should be “wearing trousers” (though he later denied sexism).

“You prepare for AGMs,” Blanc says. “You’re thinking you’re going to get the people who object to nuclear. You’re going to get the ESG [climate activists]. You’re going to get the shareholders that have got problems with claims. You prepare for everything. You do not prepare for comments like that.”

Having flown out of the country, to Aviva’s only overseas operation, in Canada, right after the AGM, Blanc landed to a furore on social media, prompting her to add her own view, on LinkedIn.

“Wow,” she wrote. She claimed to be “a little immune” to such “prejudicial rhetoric”, given how commonplace it had been. “The more senior the role I have taken, the more overt the unacceptable behaviour.” But she issued a general appeal to ensure it would be stamped out. “We have little choice but to redouble our efforts together.” The post is typical of Blanc’s firm but even-tempered style, but it went viral all the same.

She is still reeling from the 1.6mn hits the post got — and the reception her Canadian colleagues gave her. “As I walked into the town hall, all of our people stood up and applauded. It was really quite emotional. [People said:] ‘This is an important moment, Amanda, and you’ve spoken out. Good for you.’ But since then, some of the stories I’ve received about other people’s experiences are horrific.”

Five years ago, shortly after film producer Harvey Weinstein was first exposed as a sexual abuser, the decade-old #MeToo movement was revived. I ask Blanc whether, in a similar way, she thinks the incident at the Aviva AGM might re-energise the exposure of sexism in the worlds of finance and business. “I don’t want this to become my cause célèbre. I want to be judged by the Aviva results, what I achieve. Whatever I do, I just want to be judged by that,” she says. She pauses. “However, the other thing I’ve realised as I’ve moved into different roles is, you have a duty. You have a responsibility. With senior positions comes a responsibility to be able to call out.”

Hearing about the incident, Blanc says her 15-year-old daughter was unbelieving. “She was just, like, ‘No, say that again. What did they say?’ Because, of course, their mindset is that nothing is going to hold them back. Absolutely nothing is going to hold them back. They just don’t see that being a woman, being a girl, is any different to being a boss. To them, it’s just the same.”

And with that, Blanc heads out of the Cwm Farm Shop, climbs into her Tesla and heads up the valley for afternoon tea with her parents.

Patrick Jenkins is deputy editor of the Financial Times

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter