Texans feel it’s their birthright to be at the center of everything. When it came time for Texas Democratic Party chair Gilberto Hinojosa to deliver his state’s delegates to Kamala Harris during the roll call at the national convention on Tuesday, he began with the boast that Texas was the “nation’s biggest battleground.”

You can’t blame him for trying; it’s his job to make that the case. But while the long-term trend lines are pushing Texas in the direction of becoming a purple state, and recent polling shows a closer race than 2020 now that Harris leads the ticket, the Democratic and Republican presidential campaigns aren’t treating it like one. Texas is expensive to campaign in, and not quite competitive enough to justify massive expenditure. The 2020 presidential election saw Trump win the state by about 5.5 percentage points. It’s much more important (and cost-effective) to contest swing states such as Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin, so that’s where the parties will put their effort between now and November.

In truth, this is a bit of a strange year for Texas. We’re out of the conversation. Almost every presidential election since 1960 has put Texas front and center in at least one of three ways: someone from our state appears on one party’s ticket, a semi-serious candidate runs in the primary, or the state is in play in the general election. This year we have zero of three. (Unless you count the short-lived presidential candidacy of moderate Republican Will Hurd or the orb-powered campaign of Houston-born Marianne Williamson as “serious.”) We’re out of sight, out of mind, for the most part.

The party conventions this summer reflected this. Relatively few Texans spoke before the nation. Those who did, despite coming from very different perspectives, seemed to agree on an unlikely message: Texas is kind of a hellhole.

At the Republican National Convention, the problem with Texas was the border. Governor Greg Abbott and Senator Ted Cruz offered tendentious accounts of the civilizational conflict taking place in Texas thanks to Joe Biden’s immigration policies, blaming migrants, contrary to reams of evidence, for a crime wave. In their telling, the state was subsumed by violence, lawlessness, and demographic replacement—held back only by Abbott’s militarization of the border and conflict with the federal government. This reality was coming for Americans everywhere, they said, unless Trump won.

At the Democratic National Convention, the problem with Texas has been just about everything else. On Monday, Harris County judge Lina Hidalgo, helpfully identifying herself as a “county executive” rather than her precise title for the benefit of foreigners, stepped on stage and began telling the audience about “Texas leadership.” She referred back to the declaration of progressive icon and late Texas governor Ann Richards that “I’ve been tested by fire, and the fire lost.” Where Richards had been speaking figuratively, Hidalgo said, she could be literal. “In the years I’ve been in office, we’ve dealt with chemical fires, ten floods, seven hurricanes, a deadly winter freeze and, of course, the pandemic.” Another day in Houston.

But Texas wasn’t just beset by natural disasters—there were also man-made ones. The pandemic was worse than it should have been, she said, exacerbated by a leadership vacuum in the White House. The state’s power grid failed in 2021 thanks to mismanagement by the state government. When it did, Hidalgo said, Harris reached out to help.

Later that night, Jasmine Crockett, a congresswoman who represents South Dallas and is best known to a national audience for videos of her speeches and spats in hearings, had a longer and more prominent speaking slot, appearing after former nominee Hillary Clinton’s emotional address. Crockett mostly orated about Harris and Trump, and her own journey to the heights of viral fame. She warned that Trump would Texasify the nation: Speaking about abortion, she said that “right now in Texas, they want to institute the death penalty,” referring to (failed) efforts by far-right lawmakers here to make facilitating an abortion a capital crime.

That led into the most striking contribution from Texans so far at the DNC: the appearance on stage of Josh and Amanda Zurawski, an Austin couple who suffered complications when having their first child. A doctor told them their baby would not survive and that Amanda’s health would get worse without intervention, but that he could not perform an emergency abortion under state law until she deteriorated further.

In a preproduced video, the Zurawskis displayed the clothes and blanket they bought for the daughter they would have named Willow, and recounted what happened next. The doctors sent Amanda home and told her to come back when it was an emergency. Amanda suffered for three days and then returned to the hospital in a dangerous condition, when the doctors finally felt enabled to act under the law. Josh spoke of the pain of nearly losing his wife as well as his unborn daughter, urging other men to speak up for women’s reproductive rights. Amanda warned the country against following Texas’s example. “I almost died because of Trump’s abortion ban,” she said. “But I was lucky. I lived.”

They kept their remarks tightly focused on Trump, who has taken credit for the overturning of Roe v. Wade by appointing conservative judges. But in truth the parties most responsible for the Zurawskis’ suffering were the Texas Legislature and Governor Abbott, who passed and signed the antiabortion laws which created the conditions for it.

Kimberly Mata-Rubio, the mother of Lexi, a 10-year-old who died in the massacre at Uvalde’s Robb Elementary in 2021, told her story on Thursday night. Since her daughter died, her fight has been primarily with the Legislature. But she stood on stage alongside other mothers who have lost children to gun violence to talk about the issue nationally. Just before the shooting, Lexi was being recognized by her classmates for getting straight A’s, she said. “Thirty minutes later a gunman murders her, eighteen students and two teachers.” When the news reached her, she involuntarily “reach[ed] out for the daughter I will never hold again.”

The speakers kept up with the theme that Texas was a warning for the nation. But after the conventions concluded, it remained unclear how the state fits into both parties’ visions. Texas conservatives, last month, expressed unhappiness that the RNC had deviated from—by which they meant moderated on—their stance on issues such as abortion and had put figures including Amber Rose, the cofounder of the “Slut Walk,” in a prime-time speaking slot. Trump comes from a different place than the typical Texas movement conservative—twice divorced and a onetime supporter of abortion rights, he clumsily quotes scripture—and that has never been more pointedly clear to right-wingers in the state than it was when Kid Rock and Hulk Hogan warmed up Trump’s audience on the last night of the convention.

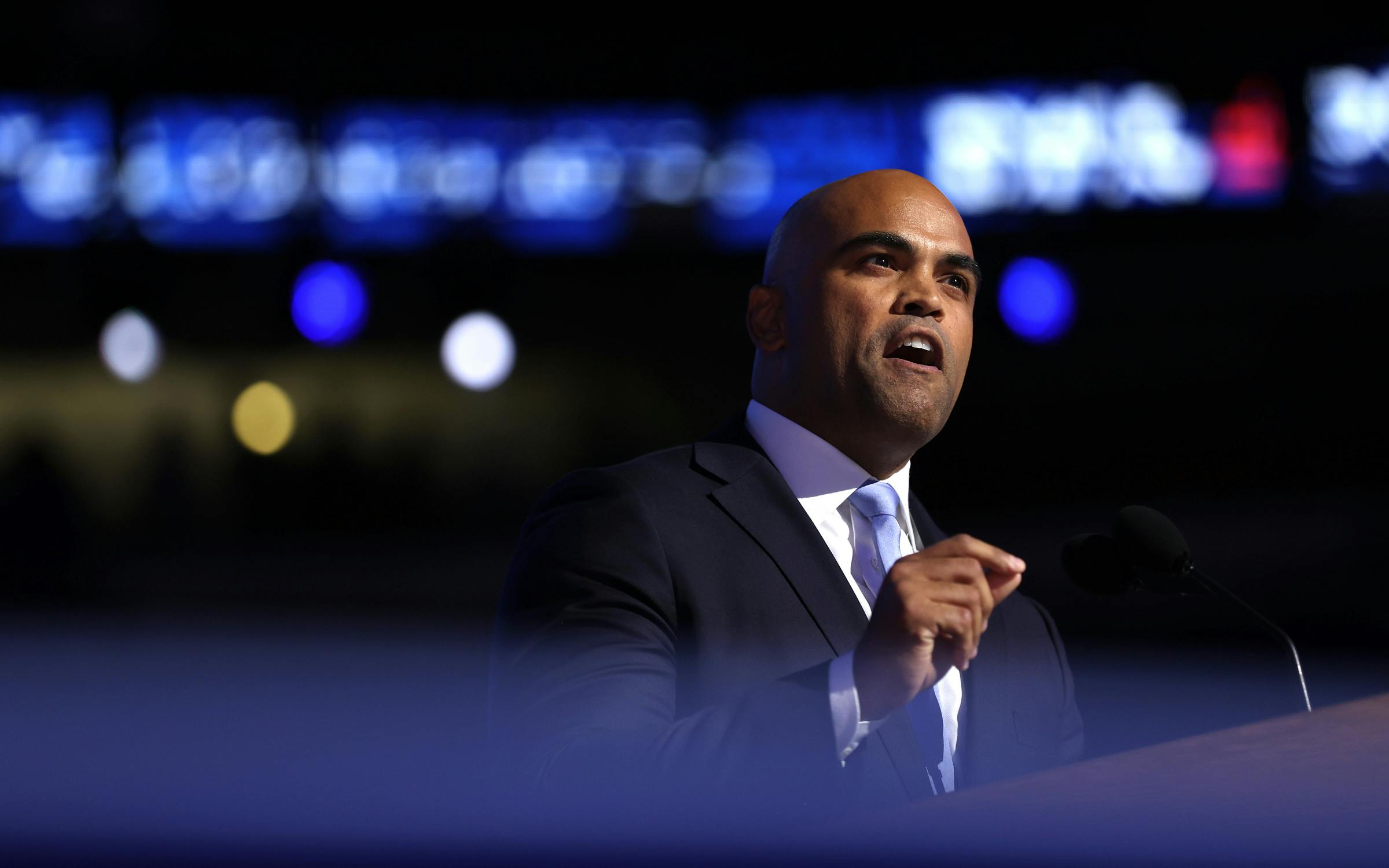

Meanwhile, Texas Democrats also weren’t given much time at their party’s gathering. In some recent DNCs, the party has highlighted someone perceived to be a rising star from here. No one quite fit the bill this year. Crockett is popular among the party’s liberal base, but is not commonly discussed as a contender to run statewide in Texas. Hidalgo is far from the national scene in her local office. It was unclear if the party’s senate candidate in Texas, Colin Allred, would even speak—but at a late hour he was assigned a berth on the last day. (In a very brief two-minute address before the nationally televised prime-time section of the convention, he introduced himself as a “dad to two perfect little boys” who would “turn the Texas Senate seat blue.”)

To be fair, there aren’t many other Texas Democrats who could qualify. Congressman Joaquin Castro, who represents San Antonio and is a notable voice in the party on foreign policy, could have been asked to speak. But he has offered a critical view of the Biden administration’s handling of the war in Gaza, and the Harris campaign has chosen to deal with that rift in the party by largely pretending it does not exist. Instead the convention highlighted Latino politicians from other states, along with Bexar County sheriff Javier Salazar, who vowed that Harris would be tough on the border.

Tellingly, the most talked-about Texan of the convention was someone who didn’t show up. On Thursday, rumors circulated that Houston’s Beyoncé would be making a surprise appearance. These unfounded rumors were so prevalent that her failure to turn up cast a pall on what was an otherwise well-received speech by Harris. That’s real power.