The detailed record of bird sightings and phenological observations around Concord, Massachusetts—from Thoreau’s notes 170 years ago to today’s studies by scientists at Boston University—provides a key to studying how climate change is affecting bird migration.

From the Spring 2023 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

One early spring morning in 1858, on hearing a Purple Finch singing, the environmental philosopher Henry David Thoreau noted in his journal: “How their note rings over the roofs of the village! You wonder that even the sleepers are not awakened by it to inquire who is there, and yet probably not another than myself observes their coming.”

Thoreau was a keen observer of nature in all seasons, as famously chronicled in his stay at a cabin in the mid-1840s in the book Walden. But he didn’t stop there, as Thoreau continued to record the first birds to arrive in spring during his walks around Walden Pond and elsewhere in Concord, Massachusetts, over the next decade. His detailed records from 1851 to 1854 are some of the earliest systematic observations of the timing of seasonal biological events, or phenology, in the United States.

Perhaps in the 1850s, Thoreau was more or less alone in detailing the comings and goings of the birdlife around Concord. But as it turns out, Thoreau’s work set the stage for regular, methodical observations of birds by an array of Concord-based ornithologists. Leaders of the field such as William Brewster and Ludlow Griscom, along with amateur ornithologist and schoolteacher Rosita Corey, contributed decades of records from the region northwest of Boston that stretch from the turn of the 20th century right up to the present. Today that tradition continues with volunteer birders fanning out across Concord every year for Christmas Bird Counts and uploading checklists to eBird in all seasons. Over the past decade, the tens of thousands of records submitted to eBird each year from Concord, and over 1 billion submitted around the globe, have provided an increasingly clear picture of where and when different birds are coming and going throughout the year.

The combined records of Thoreau and these later birders present a sweeping, 170-year historical perspective on bird migration that can’t be replicated elsewhere in the United States, making Concord an ideal living laboratory for investigating bird migration timing and the changing ecology of the plant and animal community. From Thoreau to Corey, more than 2,000 phenological records of bird spring arrival times exist for Concord, including the Eastern Phoebe in early April and the Eastern Wood-Pewee in late May. These data sets, combined with thousands more records of wildflower flowering dates and tree leaf-out times, provide the keys to studying questions like, how is climate change affecting bird migration in Concord? And, what does the future hold?

Mixed Signals on Spring Bird Arrivals

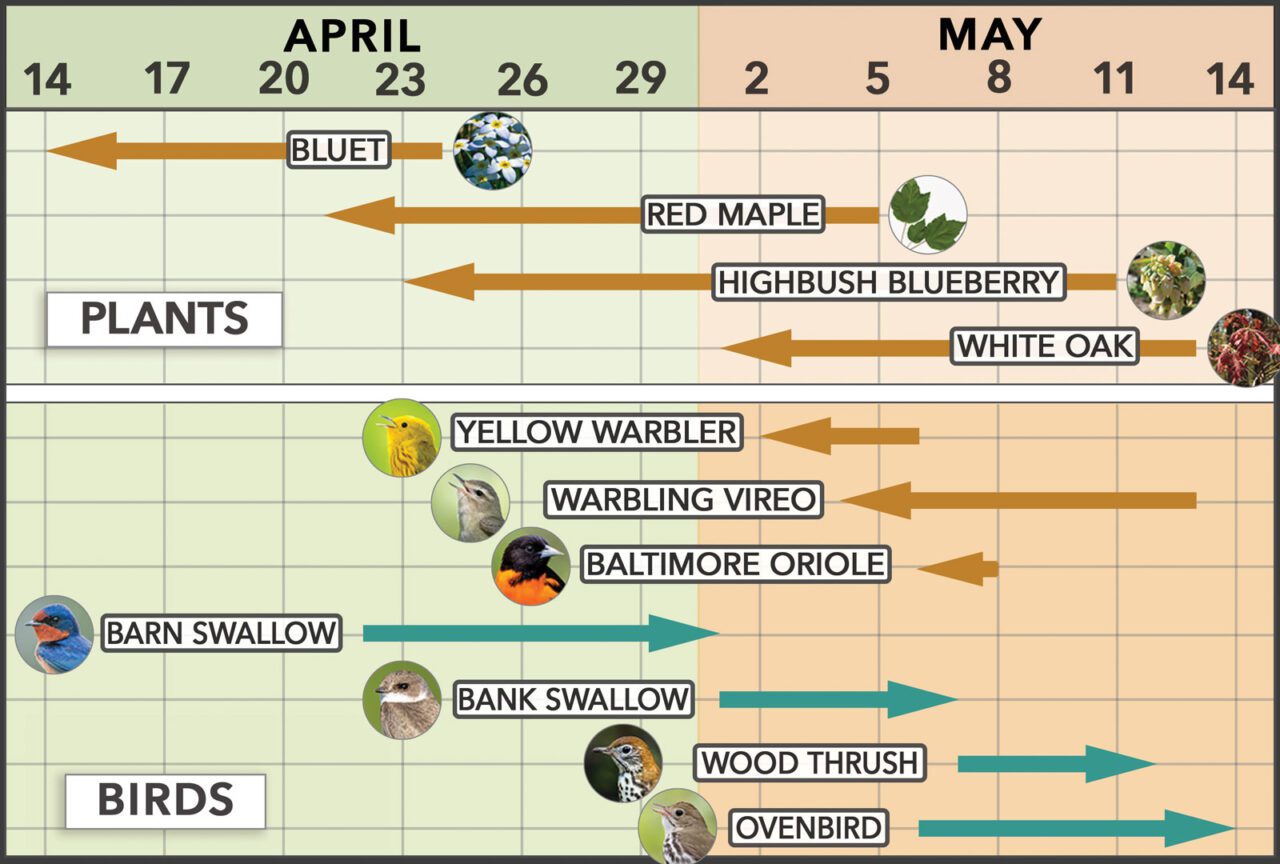

Across the migration data for 22 consistently observed species in Concord’s historical bird data, the average timing of spring arrival has not changed significantly from Thoreau’s time to the present. However, certain species do show very clear changes: Three species—Warbling Vireo, Yellow Warbler, and Baltimore Oriole—now show up at Walden significantly earlier, arriving nine days, four days, and two days earlier, respectively, than when Thoreau observed them. Four species are significantly delayed in their spring arrival compared to the 1850s, including Barn Swallow (nine days later), Ovenbird (eight days later), Bank Swallow (six days later), and Wood Thrush (five days later).

Many things have changed since the 1850s in Concord, and one of the most obvious (and easiest to measure) changes is the warming trend in temperatures. All but two springs since 2000 have been warmer than the longterm average. In warmer springs—when temperatures are about 3 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than average—seven of the 22 observed species consistently arrive earlier, including Yellow-rumped Warbler and Rose-breasted Grosbeak. In such a warm spring, bird arrivals average about four days earlier than a more typical spring.

Observations in other areas of eastern Massachusetts show similar trends. For example, bird banding records from Manomet—a nonprofit bird migration research group in Plymouth, Massachusetts—show that eight of 32 species are arriving earlier today than they did 40 years ago, changing their arrival dates by about one to 10 days.

The differences in why some migratory bird species seem to be affected by warmer springs, and others aren’t, can be partially explained by where they migrate from. Birds arriving earlier in warm Massachusetts springs tend to be short-distance migrants, coming from wintering grounds in the southern United States. Longer-distance migrants—like the Eastern Wood-Pewee, which spends the winter as far south as Bolivia in South America—are unable to anticipate and adjust their migrations based on local temperatures in North America. Their migration times are better predicted by broad global climatic factors, like the El Niño Southern Oscillation Index, which is correlated with temperature and precipitation across the southeastern United States and Central America.

Phenological Mismatches of a Shifting Spring

While some migratory bird species are arriving earlier in response to warming springs, both the Concord and Manomet data suggest that most are not changing their migration times at all. The ecological consequences of these shifts (or lack thereof) vary depending on the intricate links between birds and their ecological communities. Thoreau understood these links well, writing in his journal: “insects and the smaller animals (as well as many larger) follow vegetation. … If the buds are deceived and suffer from frost, then are the birds.”

When climate change causes closely interacting species to shift at different rates from one another, the ecological choreography of leaf-out, insect emergence, and migratory bird arrival can be thrown out of sync. This phenomenon is known as phenological mismatch. The thorough records of when plants leaf out and flower around Concord each spring provide an exceptional database for analyzing the potential for springtime phenological mismatches to affect Concord’s birds.

During his daily four-hour walks around Walden in the 1850s, Thoreau monitored blooming times of wildflowers such as marsh marigolds and pink lady’s slipper orchids. He also noted the leafing-out times of trees and shrubs like red maples and highbush blueberries. Since 2003, scientists from Boston University have picked up and continued these observations, as a means to examine how plant seasons have shifted since Thoreau’s time.

In contrast to the birds, most of Concord’s plants are consistently and strongly shifting their seasons in response to warming spring temperatures. On average, trees are leafing out two weeks earlier than in Thoreau’s time, and wildflowers are flowering about one week earlier. These shifts are strongest in warm years; in 1855, Thoreau observed highbush blueberry flowering in mid-May, but in 2012, one of the warmest springs on record, it flowered on April 1—a full six weeks earlier.

The fast-shifting plants could now be phenologically mismatched with slower-shifting birds in spring. And while the plants themselves can be important to some bird species, it’s often the insects that the plants attract that are most important to migrating birds.

When insects emerge in the spring, most of them feed on plants. And when birds arrive in Concord, they feed on insects swarming in the air, crawling on the ground, and munching on young leaves. A vital question for assessing how birds could be affected by a shifting spring, then, is whether insects are shifting quickly like plants, or slowly in sync with the birds—or, are insects shifting in a different timing pattern altogether?

Thoreau did not include insects in his systematic observations, but over the past 40 years members of the Massachusetts Butterfly Club amassed thousands of observations of butterfly spring flight times across the state. The club’s observations show that butterflies like the brown elfin and striped hairstreak are as responsive to warming spring temperatures as Concord’s plants, appearing earlier in warmer springs and earlier over time. Studies on the emergence of wild solitary bees in the eastern United States have shown that they are similarly responsive to climate change.

These lines of evidence suggest that migratory birds arriving in Concord may be out of sync with their insect food sources, threatening their ecological interactions and ultimately the health of bird populations. Evidence of spring mismatch for birds has emerged from other temperate regions as well.

For instance, in the exceptionally warm spring of 2012, a study of eBird data published in the journal Ecosphere demonstrated the potential impacts of climate change in creating phenological mismatches across North America. Here again, the evidence seemed to indicate that flexibility in bird-migration timing depended on where a species overwintered.

“Short-distance migrants were able to respond and move north as temperatures warmed, taking advantage of plants and insects as they emerged,” says Frank La Sorte, lead author on the study and senior research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

For example, the study showed that Pine Warblers overwintering in the Carolinas and Georgia could sense that spring was arriving early in 2012 in the eastern U.S., and started their northward migration accordingly. However, long-distance migrants—such as Blackpoll Warblers that migrate down to South America for the winter—were unaware of the unusually warm spring occurring on their breeding grounds. They arrived at their northern breeding grounds at the same time as usual, and according to La Sorte’s analysis of eBird records, their populations declined that summer. Such declines could reflect that long-distance migratory birds might be missing the peak abundance of their caterpillar food, while also being exposed to physiological stress from high temperatures.

This asynchrony between birds and insects is especially troubling because other research shows declines in the abundance of insects. For example, a recent study from the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire showed an 83% decline in the local population of beetles over a 43-year period. This site has also seen long-term declines in caterpillars. So not only may there be a growing timing gap between many bird migration patterns and their insect food supplies, but their overall food supply may be diminishing as well.

Despite documented insect declines at Hubbard Brook, however, new research shows bird populations there are actually increasing. Nick Rodenhouse, a professor emeritus at Wellesley College who studies long-term changes in birds and insects at the site, says the success of birds in the face of change depends on their dietary flexibility and the diversity of insects available. A diversity of insect species with varied phenologies can dampen or even eliminate peaks in availability, which minimizes the potential for mismatch.

When it comes to the future, Rodenhouse says, “it is possible that insect declines will eventually result in the decline of many bird species, but insect populations are resilient and there will be winners and losers.”

Could Mismatches be Happening in Other Seasons?

Thoreau’s observations weren’t limited to the springtime, and neither are phenological mismatches. Just like the potential for asynchrony between birds and their insect food sources in spring, there is a risk that some birds could become mismatched with a key fall food source: fleshy fruits.

Thoreau wrote about the timing of fruit ripening and leaf-color change, but he didn’t systematically record the dates of autumn events. However, the bird-banding records at Manomet provide a dataset for analyzing the timing of fall-migrating birds that goes back to 1969. Of 37 common migratory landbirds banded at Manomet, 13 species tend to migrate later in warmer autumns, including Swainson’s Thrushes, Hermit Thrushes, and Yellow-rumped (“Myrtle”) Warblers—all birds that rely on fruits during autumn migrations. In contrast, studies of fruit ripening largely show that wild fruits ripen earlier with warming temperatures or are not affected by temperature at all.

Plant communities in Concord and throughout New England have changed drastically since Thoreau’s time. Many native plant species with fleshy fruit (such as nodding trillium and flowering dogwood) have declined in abundance, while non-native plant species (such as Japanese barberry and European buckthorn) have become established and flourished. Many invasive shrubs produce an abundance of fruits that ripen later in autumn, on average, than their native counterparts, which means birds migrating later in the autumn will be more likely to encounter invasive fruits. And invasive fruits generally have less nutritional value than native fruits.

A study published in the journal Biological Conservation examined the fecal samples left by fall-migrating birds held in cloth bags while awaiting banding at Manomet, in order to assess whether birds are eating fruits from invasive plants as fuel for migration. The seeds in the bird feces indicated which fruits they were eating. Migratory birds, especially Gray Catbirds and thrushes, preferred fruits of native species, such as blueberries and black gum, and ignored abundant fruits of non-native invasive species such as bittersweet and barberry. These birds were also feeding on insects, as noted by the insect legs, wings, and head capsules found in their feces.

It appears that phenological mismatches between birds and native fruits might happen in autumn, with birds delaying their migration. However, birds’ strong preference for native fruits, and their ability to find them, may offset this potential mismatch in the timing of fruit maturation and bird migration. The extended active season for insects in warmer years may also result in more late-autumn insects for birds to eat.

Nevertheless, the potential loss or change of a key food source during autumn migration emphasizes the need to restore populations of native plants with fleshy fruits at key stopover points along migratory routes. Amanda Rodewald, the senior director of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Lab, says native plants will increasingly play a key role in migratory bird conservation in the near future.

“Restoring native plants and removing non-native invasive species can promote numbers of migratory species, many of which are specialized in their habitat needs and consume insects that are associated with native plants,” she says.

Thoreau’s Advice for Facing Climate Change

In his 1862 essay Autumnal Hints, Thoreau wrote: “We cannot see anything until we are possessed with the idea of it, take it into our heads—and then we can hardly see anything else.”

Sometimes it seems like climate change is the same way. Thoreau’s impressive set of spring observations from the 1850s gives us unparalleled insights into the effects of global climate change on a single location, the town of Concord. Yet Thoreau’s work offers far more than insights about seasonal changes. His words can almost be read as a set of instructions for people living today on how to deal with climate change.

In Walden, Thoreau tells us to observe nature carefully, to live simply, and to stand up to injustice. These are the lessons that we can use to address the climate crisis. If we carefully observe the natural world, such as the spring arrival of birds, we can bear witness to climate change. By reducing our consumption of fossil fuels and becoming involved in the political process to motivate our leaders to address climate change, we can help to protect local wildlife from the associated ecological risks.

And for Thoreau, birds were a good place to focus conservation efforts. As he wrote in his journal: “I would rather save one of these hawks than have a hundred hens and chickens. It is worth more to see them soar.”

Amanda S. Gallinat is a visiting assistant professor of environmental studies at Colby College in Maine, and Richard B. Primack is a professor of plant ecology at Boston University. Gallinat and Primack collaborated on studies cited in this article about the effects of climate change on bird-migration times in New England as part of the research conducted by the Primack Lab, which for the past 20 years has focused on climate change ecology analyses while using the field notes of Henry David Thoreau at Walden Pond as a baseline.