In poker lore, the best stories tend to begin with jackpot wins, steady nerves, or the occasional threat of murder. Doyle Brunson has all those tall tales—and we’ll get to them in due time. He has won millions while bluffing, stared down killers in parking lots, and pried his chips—quite literally—from the hands of death.

But this saga doesn’t start there. Instead, it starts with Brunson in retreat.

It was May 1972 at Binion’s Horseshoe, in downtown Las Vegas. Tables were jammed together in an improvised poker room to seat eight players who had each bought in at $10,000 for a chance to win the third annual World Series of Poker. Reporters crowded into the casino with their cameras and tape recorders, but it was nothing like the scene at today’s WSOPs. This tournament wasn’t broadcast on cable TV or treated like a sport. It wasn’t even treated like a game. Texas Hold ’Em, now the most played poker variation in the world, had been in Vegas casinos less than a decade. In 1970 there had been only fifty poker tables in the entire city. This world series was a sideshow meant to drum up business for the casino, and the competitors were as strange as if Mark Twain characters had jumped off the page and found their way to the desert for a piece of the action. An article in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram described the event: “In the clockless world of gambling, peopled as it is with optimists, liars, fools and lunatics, it is the lot of the poker player to be set apart and regarded as a curiosity.”

One of those curiosities was Brunson, with his thick-rimmed glasses, his thinning hair, and his gut that hung over the table. He was perhaps the best player in the world, wielding a domineering strategy few had ever seen. Yet even the biggest poker fan wouldn’t have known the name “Doyle Brunson” back then. He tried to avoid the reporters, and when he did speak with them, he used the pseudonym Adrian Doyle and said he came from Texas and that some people called him Texas Dolly.

The field was whittled down one player after another, and, bit by bit, Brunson amassed a war chest of chips. Three players remained. Soon, a champion would be crowned. The crowd grew. The cameras flashed.

That’s when Brunson started to lose, folding each hand without even trying to win. Jack Binion, the casino’s president, saw what was happening. He paused the game and marched the players into a private office, where he tore into Brunson.

“You’re going to cause a big scandal here,” Binion said. “You just can’t do this.”

“Jack,” Brunson explained, “I just don’t want the publicity.”

Back in Longworth, the tiny, conservative West Texas town where Brunson grew up, most folks thought he made an honest living. They knew him as the son of a farmer, a former state-champion athlete, and a master’s graduate from a Baptist college. If they found out how he really spent his days, if they knew who he spent his time with, well—Brunson was worried that his entire family would be shunned.

And so Texas Dolly walked out of Binion’s office, across the casino floor, and out of the Horseshoe. Here was a man known to boast that he had once played poker for five straight days without sleeping. Now he claimed he was too tired, nauseated, and dizzy to even sit at the table.

As he turned his back on a world title, he told himself there would be other fortunes to win, other chapters of his legend to write. And maybe, one day, they would come without the guilt.

Early one afternoon this March, Brunson steered a blue Cadillac Escalade off the Las Vegas Strip, skirting the Bellagio’s famous fountain on the way into the casino’s north valet entrance. As he handed his keys to the attendant, the buzz began. It only intensified as he raced his mobility scooter across the marble floors, swerving around slot machines and ATMs and tourists. “I’m afraid I drive like a NASCAR driver,” he says.

Brunson is now 88, with a smooth, bald head under his signature white Stetson and eyes that seem stuck in a squint. He looks his age, but his bright smile still shimmers, and his belly laugh still thunders. He zipped into the poker area, and as he wove through the low-limit tables, players glanced up from their cards. They removed their earbuds, peered over their sunglasses, and gave their tablemates looks that betrayed their poker faces. He sped by them and headed straight into a private space at the back. It’s called the Legends Room, and his picture hangs on the wall. He pulled up to his usual spot and greeted the regulars. He asked to be dealt in.

Here, the buzz crescendoed. You could understand the excitement. Watching Doyle Brunson play poker at the Bellagio is like watching Tiger Woods play Augusta—if you could buy in for a chance to tee off with Tiger at Amen Corner.

Since his exit at the 1972 WSOP, Brunson has become nothing less than the most legendary poker player of all time. Name a seminal moment in the game’s past, and chances are he was sitting at the table. “He is the bridge between history and today,” says Daniel Negreanu, a past WSOP champion. Brunson has starred in just about every poker TV show ever aired—High Stakes Poker, Poker After Dark, and Poker Superstars, to name a few—and his how-to book, Super/System, is considered a bible of the game. He played in the very first WSOP, in 1970, just as he did in the event’s fifty-second installment, last year. Over the decades, the WSOP has grown into a massive production that dominates Vegas for six weeks during the summer and features 88 in-person events in multiple variations of poker, with thousands of players vying not only for money and bragging rights but also for the diamond-and-gold championship bracelets that are the game’s version of boxing title belts. The most famous of these competitions is the Main Event, a Hold ’Em showdown that airs on CBS Sports Network. Brunson has won the Main Event twice, in 1976 and 1977, and he’s added eight other bracelets along the way. Only three other players have won multiple Main Events, and Brunson is tied with fellow all-time greats Phil Ivey and Johnny Chan for the second-most bracelets ever earned, with ten, behind only Phil Hellmuth, who has sixteen.

But Brunson’s real reputation was born in games like this one: on a nondescript afternoon, in Vegas, behind closed doors, with as much as a million dollars in the pot. Brunson still plays cash games at least once a week, although many friends try to get him to the tables even more often. Until his eightieth birthday he played three hundred times a year, gambling all night and sleeping when the sun rose. “We used to bet all we had, day after day,” Brunson says in Al Alvarez’s book The Biggest Game in Town. “And every other day we went broke.”

These days, he tries to make it home before dinner; he says his wife, Louise, has already spent too many long nights worrying about him. Though nothing would be more worrisome than if Brunson quit cards altogether. “I’m telling you, he will die if he stays home,” says Eli Elezra, a recent inductee to the Poker Hall of Fame and a frequent tablemate of Brunson’s.

Brunson has never craved the spotlight, which not only goes against his nature, but also disrupts his strategy at the card table. “If I could, I’d go back to being an anonymous poker player.”

Maybe so. During the height of the coronavirus pandemic, Brunson didn’t play for nearly a year. In that time, he was hospitalized with pneumonia and, he says, suffered physical withdrawals from being away from the game. “I played so much that it’s just a part of my life,” he says. Without poker, Brunson felt dizzy, depressed, and lethargic. “Just like a dope fade.”

“He needs the adrenaline. He needs the bad beat,” says Elezra, describing the jolt gamblers feel after their most crushing losses. “He needs it to live.” But Brunson has never craved the spotlight, which not only goes against his nature, but also disrupts his strategy at the card table. “If I could, I’d go back to being an anonymous poker player,” he has said. In tournaments, competitors will go all in against him nearly every time, just so they can return home and tell their garage game buddies that they won a hand against Texas Dolly. “Most people have read [my] book,” he says, “and they always think I’m bluffing.”

Brunson claims he’s done playing in the WSOP Main Event, that 2021 was his final run. The crowds have grown so thick and the fanfare so overwhelming that he can hardly get his scooter to his assigned table. But he’s sworn off tournaments before, and that didn’t stop him from joining last year’s contest. It wasn’t his best showing, but expert observers say he did what he could in difficult situations. “Most players likely would have been gone much earlier,” wrote Jon Sofen for PokerNews. So perhaps this semiretirement is just one more bluff.

The public’s embrace of Brunson and of poker writ large is something he could hardly have imagined in 1972. When he sat down with another chance to win the Main Event in 1976, Brunson still coveted the approval of a society that had yet to accept professional gambling as much more than the province of eccentrics and degenerates. But by then he was done hiding. He decided right there to try to change how the world saw poker players. He won that year and the next, and the book, the press, and the TV appearances all followed.

That might have been Brunson’s most impressive wager—as well as his most lasting contribution to the game. His charisma helped lift poker

from smoky back rooms to stages like the Bellagio: opulent, well lit, romantic, and made for TV. For decades, Hollywood rarely depicted poker outside of gangster movies and westerns; by the time Rounders was released, in 1998, Super/System appeared in one of the film’s opening shots and the voice-over name-checked Brunson three times.

In the mid-aughts, Matt Damon, the star of that movie, joined Brunson’s game at the Bellagio. He brought a pal: Leonardo DiCaprio.

As always, the onlookers were there, straining to see. And when a group finally approached to ask for photos and autographs, they ignored the Hollywood celebrities and went straight for Brunson.

DiCaprio, Brunson says, “just played real tight,” meaning he wasn’t aggressive. Brunson has plenty of other A-list gambling buddies and a curt scouting report on everyone from Cary Grant (“wasn’t very good”) to Tobey Maguire (“on the professional level, almost”). He has golfed with Michael Jordan and was there when Willie Nelson lost a reported $400,000 in “high-stakes” dominoes. Last August, Senator Ted Cruz played a game with Brunson (“He was very good . . . He really talked to me a lot”). The respect was mutual. “Doyle Brunson is an all-time Texas great and a legendary poker player,” Cruz told Texas Monthly. “He’s a man of grace, charm, and incredible savvy insight. It was amazing—truly a bucket-list moment—when I had the honor to sit down and play poker with Texas Dolly himself.”

A few months ago, Brunson transferred most of his money to his children Pam and Todd (both are accomplished poker players themselves). He has earned more than $6 million in tournaments and has won and lost so many millions more in private games that even those who know him best struggle to estimate his career winnings. Poker players are famously tight-lipped when it comes to discussing their net worth, and Brunson is no different. He won’t say why he gave away his fortune or how much remains; he just explains the decision with a shrug: “I don’t know; I just did.”

Now he doesn’t have the bankroll to play in the high-stakes, no-limit games that had long been his bread and butter. Instead, he plays what he calls “cheap poker,” where the minimum opening bet on each hand is $300. During a typical five-hour session, he says, he needs around $20,000 worth of chips just to get started. Cheap poker, indeed.

And yes, he still wins.

Decades ago, Brunson bought land in Northwest Montana, on Flathead Lake, and even when he’s not visiting, he tries to keep the Big Sky with him. His car has Montana plates (along with a “Don’t Mess With Texas” bumper sticker), and his phone number begins with a Montana area code. Just inside his lake house’s entrance are two framed photos of him after his Main Event victories. Between them, a custom-made sign reads “A Long Way From Longworth.”

When Brunson was born, in 1933, Longworth was an unincorporated West Texas town with a population of around two hundred. There was a general store, a one-room elementary school, and two churches. The nearest city was Sweetwater, fifteen miles to the south. His family home didn’t get electricity until after he turned six, and throughout Brunson’s youth, it lacked indoor plumbing. The door to the outhouse creaked every time someone opened it. Railroad tracks cut through the cotton fields in the backyard, and often, around dinnertime, the wall-shaking rattle of a passing train was quickly followed by a knock on the back door. Hoboes knew that Brunson’s mother, Mealia, would feed them a warm supper; all they had to do was jump from the boxcar and cross the rows of crops. After dinner, the next train would carry them along.

Brunson’s father, John, seldom spoke and rarely gave his three children much attention. He ran the family’s farm, and the kids grew up picking cotton by hand. They sold it for a penny a pound. Yet money never seemed to be an issue for the Brunsons. Somehow, John always seemed to have just enough.

Three other children Brunson’s age lived in town, one girl and two boys. The trio of boys spent long afternoons playing baseball with one pitcher, one fielder, and one hitter, using a broomstick as a bat. They shot hoops on a dusty outdoor court where only Brunson appeared to be able to adjust his accuracy when the prairie wind blew. They swam in stock tanks and pretended to be cowboys.

Spend any amount of time with Brunson and it’s clear the man hates losing. That spirit was born on those slow afternoons in Longworth. In his memoir, The Godfather of Poker, Brunson calls himself a late bloomer in sports, but by the time he enrolled at Sweetwater High, he was a natural at everything he tried—except football, which his parents forbade him from joining. He was too small, they believed, at just five foot seven and 140 pounds.

In track, his specialty was the mile, and he ran it fast enough to qualify for the state meet, in Austin. Radio stations carried the event live across Texas, and Brunson’s father tuned in from Longworth. His boy would be challenging the previous year’s reigning champion and runner-up, both of whom were favorites to repeat. When the race began, the broadcaster mentioned only those two names, painting the picture of a neck-and-neck battle for first place. John’s heart sank. He would later tell his son, “I just figured you got down to that big meet and got outclassed.”

The games Brunson frequented in his prime could see each player win or lose half a million dollars only to come back and do it again the next day.

But soon, the voice cut through the radio again: “Well, ladies and gentlemen, it looks like this duel was all for second place. Doyle Brunson, from Sweetwater, is about fifty yards out in front, and it looks like he’s gonna stay there.” Brunson was the 1950 state champion in the mile, with a time of 4:38.01.

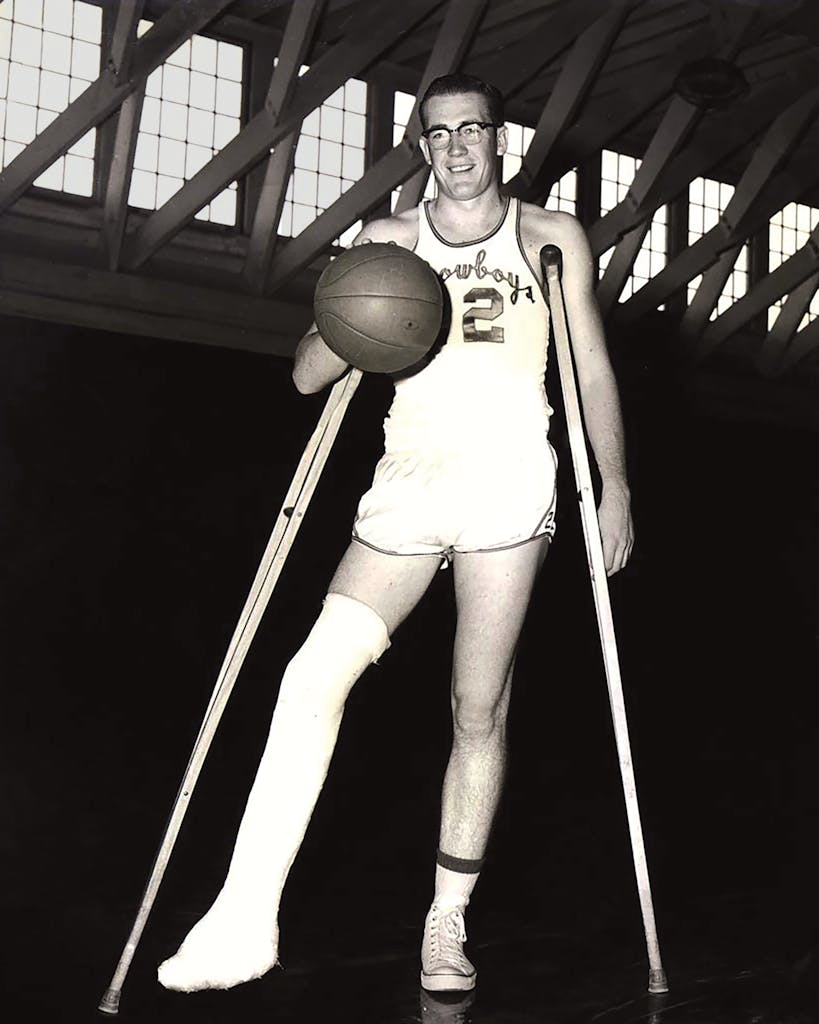

But Brunson’s main love was basketball. This was the late forties, shortly after the founding of the NBA, and the sport was so young that high school coaches in West Texas sometimes knew less about the game than their players did. Brunson mostly ignored the coaches at Sweetwater and instead cribbed his moves from the team’s veterans. Before long, he had built himself into a star player—aided by a growth spurt that left him standing six foot two heading into junior year. He played guard and was considered one of the deadliest long-range shooters in Texas. He wore glasses on the court, and when defenders fouled him, the frames dug into his skin, leaving Brunson’s eyebrows dotted with scars.

In 1949 he led Sweetwater to the state tournament, and on the eve of the semifinals, he visited the hotel room of some classmates who’d made the trip to Austin as fans. They were playing poker—Seven-Card Stud and Five-Card Draw—and they offered to teach Brunson. He had seen the game only in westerns. They bet dimes, then quarters, gambling deep into the evening. Brunson won a few dollars and headed back to his room around midnight.

Even now, he can recall specific hands from throughout his life with photographic accuracy, certain cards that won him millions and made him famous. He remembers that first game too. “Easy money,” he says in his memoir.

They say nobody stays lucky in Las Vegas. On a typical day, the cash games that Brunson frequented in his betting prime could see each player win or lose half a million dollars only to come back and do it again the next. A few bad nights could leave anyone—even a champion—with nothing. Brunson says he once lost $6 million to a player named Chip Reese. He’s had hot streaks and cold streaks since then, but if overall winnings are the measure of success, you could say that Brunson has been getting lucky for more than half a century, in card rooms from Fort Worth to Macau and everywhere in between.

“Nobody gets lucky consistently,” he says. You can win a few hands here and there with no real skill. You might even win an entire tournament that way. But grinding at a table day after day and coming out on top is a different story. In all the games he’s played, Brunson has made a royal flush, the best hand in the game, just twice, and still, poker has been his primary source of income for 66 years. Besides the year in which he lost the $6 million, he says, he has never finished in the red.

The keys to his success hearken back to an earlier era of the game. Brunson does not wear dark sunglasses when he plays. He does not wear earbuds to block out noise, like many modern-day players do. Other competitors zip hoodies up to their eyes, hiding as much of their faces as possible from opponents adept at spotting tells—subtle giveaways of a gambler’s mental state. “I think they should outlaw all that,” Brunson says. He prefers a purer game, wearing a button-down shirt, and sometimes a sports coat, with his white Stetson. He talks to others at his table. “I played with him a few months ago,” says Daniel Negreanu. “He feels like, to me, at eighty-eight, sharper than he did five years ago—like, better. He’s playing better now than he was a few years ago.”

Today, younger players prepare using computer algorithms that help determine exactly which hands to play and which to fold, as well as the precise amounts to bet based on probability. Brunson has studied these methods, but he believes he can beat the opponents who use them, and he’s not the only one who thinks so. He might not win the first game against a new rival. It might take him a month, even a year, but eventually, he’ll find an edge. He has said he can catch opponents bluffing by watching their neck veins for signs of an increased heart rate. Against the new wave of analytical players, he’ll play erratically, betting hands a computer model would expect any sane person to fold just to throw off the competition. Poker historian Nolan Dalla says he’s confident Brunson could beat a table full of amateurs without even looking at his cards. “Poker is a game of people,” Brunson often says.

“There’s mathematics, there’s fundamentals, there’s strategic ways to approach different things,” Negreanu explains. “You can be studious and learn the game that way. What Doyle is talking about is adjusting his strategy to the person—playing the player. Understanding what kind of person he’s dealing with, what types of things they like to do. Are they someone who likes to lie a lot and bluff? Or just someone who plays it straight? And when he knows that, he adapts the strategy. So he’s playing the people. He’s always playing tendencies. He’s also adjusting based on ‘How’s that person doing? Are they losing a lot? And if so, are they broken in their mind?’ ”

Brunson can’t fully explain the hold gambling has on him, but the attraction has never wavered since that first poker game in an Austin hotel room. The Sweetwater basketball team lost the next morning, but Brunson performed well enough that the University of Texas offered him spots on the Longhorns’ basketball and track teams. Brunson wanted to accept, but he waited too long to fill out the paperwork, and by the time he was ready to apply, UT had allotted all its scholarships. Instead, Brunson landed at Hardin-Simmons University, a Baptist college in Abilene that competed in the Border Conference, which in those days counted Arizona, Arizona State, and Texas Tech among its members.

On weekends he’d travel to college towns to play poker. Lubbock, College Station, Austin—the bigger the school, the more fraternity brothers to fleece.

At Hardin-Simmons, Brunson’s athletic scholarship included a $15 monthly stipend, what the school called “laundry money.” He used the cash to stake himself in late-night poker games with other undergrads—and also to wager on just about anything he could think of. He’d turn to friends and bet a dollar that he could throw a rock and hit a telephone pole. Five separate times, the school’s disciplinary board called Brunson in to warn him about gambling.

Another student might have been expelled, but Brunson says his status as a star athlete saved him. On the track, his mile time kept dropping—all the way to 4:18. He was more serious about basketball, and in 1953, his junior year, he led the Cowboys to a conference championship over Arizona. That earned the school a spot in the NCAA Tournament and put Brunson on the NBA’s radar. The Minneapolis Lakers sent scouts to Abilene, and they informed Hardin-Simmons’ coach that they planned to pick Brunson in the first round of the following year’s draft. Brunson thought his future was set. (Decades later, while sitting across a poker table from then–Lakers owner Jerry Buss, Brunson asked if the franchise still had any scouting tape of his college games. “No,” Buss replied. “After fifty years, we throw them away.”)

The summer before his senior year, Brunson returned home to Longworth and found a job working with Sheetrock at the local gypsum plant. One day, while loading the material from a forklift to a truck, he noticed a stack starting to fall. Brunson rushed over and tried to catch it before it toppled over, but he couldn’t stop the two-thousand-pound pile from falling on him. It crashed directly onto his right shin, snapping both his tibia and fibula. He collapsed, the exposed bone jutting out of his leg. A coworker covered him with a blanket, as if he were already dead.

“My God,” Brunson thought. “I’ll never play basketball again.”

He couldn’t have known it then, but it might have been the first time in Brunson’s life that he got truly lucky.

There was no money in basketball in the fifties; the average NBA player’s salary was a few thousand dollars. If he’d gone on to play professionally, Brunson would have rushed to marry his college sweetheart, and, after basketball, he probably would have returned to West Texas to become a teacher—a principal, maybe.

That would have been an admirable outcome, and he probably would have been happy with it, but today, he’s glad his injury sent him down a different path. Though when he was trapped in a white cast from foot to mid-thigh, he struggled to imagine any future at all. While he was still recovering, Brunson and some college friends got to talking about their long-range plans. They spoke of becoming writers and politicians; then they turned to Brunson. He told them he wanted to make a lot of money, and when they asked how, he replied, “I don’t know.”

He enrolled in graduate school at Hardin-Simmons to buy some time, earning a dual master’s degree in business and education. Without the distraction of sports, his grades improved, but he was broke. On weekends he’d travel to college towns to play poker. Lubbock, College Station, Austin—the bigger the school, the more fraternity brothers to fleece. Almost always, he rode back to Abilene with their allowance money. “I could see that I was better than most of them,” he says, before issuing a swift correction. “Or all of them.”

After graduation, he considered teaching but wanted better pay, given his advanced degree. He took a job selling adding machines in Fort Worth. “I thought I would get a better job,” he says, still miffed that he received no more lucrative offers. “I wasn’t a salesman.” On his first day, he walked up to a potential customer and launched into his pitch. “The guy just looked at me, turned around, and pointed at the door.”

In seven months on the job, he failed to make a single sale—a harbinger of a cursed business sense that would follow him for the rest of his life. (Brunson has lost hundreds of thousands on investments over the years, from gold and emerald mines to teeth-cleaning chewing gum to expeditions aimed at raising the Titanic and discovering Noah’s ark.) One day, while making his rounds, Brunson ran across a poker game in the back room of a pool hall. The first time he bought in, he “cleared a month’s salary in less than three hours.” It wasn’t long before he ditched sales and decided to play poker full-time.

That Brunson had recently moved to Fort Worth was another stroke of fortune. In the mid-fifties, Fort Worth’s Jacksboro Highway and Exchange Avenue were dotted with colorful characters and dark rooms filled with card tables. Poker was illegal, but many of the games’ organizers cut deals with local police to allow them to operate. “Exchange Avenue was maybe the most dangerous street in America. There was nothing out there but thieves and pimps and killers,” Brunson says. “It was amazing.”

He started small, slowly figuring out strategies and developing his skills. He bet and bluffed against characters with names like “Treetop” Jack Straus, Corky McCorquodale, and Duck Mallard in games of Seven-Card Stud and Ace-to-Five Lowball. Elmer Sharp ran one game out of his garage near Jacksboro Highway, where he kept a live bear as a pet. When business was slow, Sharp would wrestle the animal. Brunson says he once played five straight days at Sharp’s, stopping only to eat, drink, and use the bathroom. Others drank heavily and popped pills to stay alert during these marathon sessions, but Brunson rarely got drunk and always avoided drugs. He ran on coffee and sweets.

Violence was a fact of life in Brunson’s Fort Worth. “You never knew what would happen,” he writes in his memoir, “but you sure as heck knew something would.” He was arrested more times than he can count and carried a pistol with him at all times. When he went out to eat, he sat facing the door. In the middle of one game, near midnight, a man walked up to a player a table over from Brunson, put a gun to the back of the player’s head, and pulled the trigger. His brain splattered against the wall. Brunson still remembers his own cards when it happened—two pair, aces and sevens. He grabbed his chips and ran out the back, afraid not so much of the shooting as of the police, and hid in an ice-cold creek until the situation cooled down.

In another incident, while playing a private game of Ace-to-Five Lowball, a poker variation in which the object is to have the five lowest cards, Brunson noticed that every time he bluffed, his opponent, a man named Red Dodson, would fold. Brunson was making a killing, and so, once again, he bet big. Only this time, Dodson bet with him. “I know y’all have been bluffing me all night,” Dodson said. “Let’s see what you do now.”

Dodson turned his cards over, grinning. He had the second-best hand in the game: an ace, two, three, four, and six. There was no way he could lose—or so he thought. When Brunson revealed his cards, Dodson stared in horror at an ace, two, three, four, and five—the best hand possible. “Red’s face turned white, his eyes rolled back, and he started turning blue,” Brunson writes. “Red fell out of his chair and was dead before he hit the floor.” While they waited for the paramedics to arrive, Brunson collected the pot. “I felt bad,” he writes, “but that’s poker, and bad beats happen.”

When Brunson went home for the holidays in 1957, his father asked him and his brother if they wanted to play some poker. Brunson was surprised. He’d been unaware his father even knew how to play. There was no money on the table—they bet only matchsticks—and Brunson did his best to play like a casual gambler. His competitive side couldn’t take losing, though, and he tried a bluff. His dad saw right through it. “How in the world would you call that?” Brunson asked. Unimpressed, his father replied, “I’ve been seeing plays like that for forty years.” As it turned out, he’d put Brunson’s brother and sister through college with winnings from Sweetwater poker games.

Brunson never told his father the truth of what he did for work. He never got the chance. John died just a year after that game, and Brunson still thinks of him. “I was always hoping he’d ask about what I was doing, give me a kind word about something,” he writes. “I suppose I’d even have settled for being yelled at.” Maybe poker could have finally brought them together. He wonders now if he inherited a “poker gene,” something in his blood that calls him to the tables night after night—the same longing that called his father too.

Nobody is quite sure where or how Texas Hold ’Em originated. Some say it was invented by cowboys who were short on cards and had to improvise to include more players. In 2007 the Texas Legislature recognized Robstown, outside Corpus Christi, as the game’s founding place, but reliable details are murky. Dallas gamblers supposedly adopted the variation in the twenties. We do know that in the fifties, Hold ’Em—or, as it was also known, Hold Me Darling or F— ’Em—was hardly synonymous with poker like it is today. In 1958, when he traveled to a private card room in Granbury, forty miles south of Fort Worth, Brunson had never heard of Hold ’Em. But he knew that the man running the game drank too much and bet high. He smelled opportunity.

In Granbury, Brunson asked the regulars to explain the rules. “I grasped the correct strategy right away,” he writes. “Play big cards and use position as my two big weapons.”

In retrospect, that night might be considered Hold ’Em’s big bang; it’s as far back as the record goes. Still, it would be another decade before Brunson and other Texas gamblers brought Hold ’Em to Vegas, and when they did, it wasn’t to spread the good word about a challenging style of poker. It was to clean out some suckers. The Texans knew how to win at Hold ’Em, and the Vegas gamblers did not. “I went seven years without losing in a big poker game,” says Brunson. “All the wise guys thought I was cheating, which I wasn’t. It was just that the competition was so easy.”

As he traveled from game to game, Brunson met fellow gamblers “Amarillo Slim” Preston, a wisecracking rancher, and Bryan “Sailor” Roberts, named for a stint in the Navy. They became fast friends, joining forces to form a barnstorming big three of Texas gambling. They would bet on anything and

everything—both with and against one another. During a road trip through Mexico, Brunson looked out of their station wagon at the Sierra Madres. “Doyle,” said Roberts, “how long you think it would take you to shinny up that mountain?”

Brunson took stock of the situation. “Oh, I could climb it in two hours easy,” he said. Right then, the car skidded to a stop, they each put up $2,000, and Brunson was off to the races. In Slim’s recollection, Brunson “shinnied up that mountain like a mountain goat on a mission.” Even with his bad leg, he beat the time, and Roberts was so frustrated when Brunson arrived back at the station wagon that he refused to hand Brunson the money. He threw it on the floorboard instead, and Brunson just let it lie there, where it stayed as they drove off in search of their next wager.

When Louise asked Brunson what he did for work, he told her he was a bookmaker. She thought he said “bookkeeper.” It would be months before she realized her mistake.

The trio found strength in numbers, playing from a single bankroll so a bad night wouldn’t leave one of them broke. They watched one another’s backs, although they still got robbed occasionally. They arranged themselves throughout the room to spot cheaters, although they themselves never cheated. (“If I needed to, I might have,” says Brunson.) Most important, they helped one another study the game; after long nights of gambling, they would replay critical hands back at their hotel. They’d go through deck after deck, working out a rough understanding of the probabilities that certain hands would lead to wins. Players today use powerful computers; Brunson and his friends grasped the odds through brute repetition.

One day, Brunson was with Roberts at the Dixie Club, in San Angelo, when he noticed a woman dancing to country music. He found out she was a pharmacist named Louise. They danced. He asked her to coffee. She said no. The next day, Brunson went to the pharmacy, pretending he needed vitamins, so that he could talk with her. He kept coming back, every time under a different pretense, and he says it wasn’t long before he had bought nearly every item in the store. “She sold me toys, vitamins, multivitamins, aspirin, everything,” he writes. “I bought every contraption she recommended.” He never quite won her over, though, and Brunson gave up until months later, when he saw her out with another man. Brunson winked, and Louise waved back. “Well, maybe I’ve still got a shot,” he thought. So he went back to the pharmacy and asked her to dinner. This time, she said yes.

When Louise asked Brunson what he did for work, he told her he was a bookmaker. She thought he said “bookkeeper.” It would be months before she realized her mistake. By then, it didn’t matter. She was in love.

They married in 1962 at a funeral home in La Marque, across the bay from Galveston. Brunson’s brother-in-law worked there, and in any case, he says, “the chapel was lovely.” A few days earlier, when Louise was waiting to head to the courthouse for their marriage license, it was Roberts who arrived to accompany her instead of Brunson. Her groom was at a poker game, and he was winning. They figured Roberts could stand in his place. Besides, as Brunson remembers, “we needed the money.”

Downtown Las Vegas looks today like something out of Blade Runner. Fremont Street, less than ten miles north of the Strip, used to be where the town’s biggest gamblers lorded over the action at casinos like the Golden Nugget and Benny Binion’s Horseshoe. The area has since been redeveloped as an outdoor mall and promenade, where pop music pulses from speakers and a massive LED screen arches over the street like an artificial, electric-pink-and-orange sky.

The Horseshoe is still there, although it’s now called Binion’s. Inside, the ceilings are low, and the air is stale with nicotine. The flashing lights and electronic bleeps of slot machines are everywhere, and only three framed photos on the wall behind the cashier’s cage are left to commemorate the casino’s status as the birthplace of the World Series of Poker. Brunson appears in two of them, one that features him and the late poker pro Stu Ungar seated at the 1980 event’s final table and another in which he’s shaking hands with broadcaster Brent Musburger. The poker tables at Binion’s have closed during the pandemic, and as one cashier says, “I don’t know if they’re gonna come back.”

Vegas constantly erases its own history. Harrah’s Entertainment bought the rights to the WSOP in 2004, and in doing so, the company acquired the Horseshoe name. This summer’s WSOP has already begun at the Bally’s casino complex on the Strip, which is in the process of being renovated and rebranded as the Horseshoe. The Main Event will start July 3. At the opening press conference, organizers were keen to highlight the old Horseshoe as the WSOP’s birthplace, but the glitzy, corporate air of the endeavor had little in common with the spirit of the original casino or its boss, Benny Binion.

Binion was a Dallas crime boss who had already been convicted of one homicide and charged with two more by the time he moved to Vegas. He left Texas in 1946—“My sheriff got beat in the election,” he said—and headed to Nevada with $2 million stuffed inside a pair of suitcases. There, he bought the Horseshoe and turned it into a no-frills paradise for gamblers. Binion’s casino would take any bet, without limits, and the house always paid. The Sombrero Room restaurant served beef from his ranch in Montana and poured bowls of spicy chili using a recipe that Binion had learned from a lawman who had been part of the team that ambushed Bonnie and Clyde and who used to cook for inmates in the Dallas jail. Binion looked out for other Texans in Vegas, and when Brunson moved to the city, in 1973, Binion took him under his wing. They ate lunch together most days, often with the mayor and other local power players.

Brunson’s connection to Binion also gave him protection during a period in which rival syndicates clashed over their cuts of nearly every dollar won, lost, earned, or stolen in Vegas. When Brunson arrived, the city’s most vicious gangster was Tony “the Ant” Spilotro, who, according to some accounts, committed at least two dozen murders and who inspired Joe Pesci’s character in Casino. Word eventually reached Brunson that Spilotro wanted 25 percent of his winnings. The next time they saw each other, Brunson asked why he should accept those terms.

“If you don’t like it,” Spilotro said, “I’ll stick twelve ice picks in that big fat gut of yours.”

“You can’t kill everyone,” Brunson told the mobster at a subsequent meeting.

“I won’t have to kill everyone,” Spilotro said. “Just the first one.”

Despite the threats, Spilotro never laid a hand on Brunson, who says the only reason he’s still alive is because Spilotro knew better than to cross Benny Binion. For his part, Brunson’s participation helped Binion and his son, Jack, launch the inaugural World Series of Poker. That title didn’t mean much—at the time, demand for the game was so scarce that many Vegas casinos lacked poker rooms. The event wound up being more convention than tournament. The Binions invited the best three dozen players in the world, many of whom were Texan, to play different variations of poker over several days and then vote on the overall champion. It wasn’t until the following year that the tournament adopted an elimination format. The Binions liked the event because it brought people into the casino. Players such as Brunson liked it because it made for easy pickings in side games with tourists who wanted to try their luck against pros.

Brunson got a ten and a two. “It’s one of the worst hands you can be dealt,” Negreanu says. “Absolute trash.” But Brunson sensed that Alto didn’t have anything either.

In 1976 Brunson made it back to the final table for the first time since he had conceded the title four years earlier. This time, he played to win. It was down to him and a gambler from Houston, Jesse Alto. Brunson chipped away at Alto’s stack, wearing him down little by little until Brunson finally won a big hand. Brunson knew that Alto tended to get impatient after losing big and thought, “If I can win the next hand, I might break him.”

The dealer slid the men their cards, and Brunson turned up a ten and a two. “It’s one of the worst hands you can be dealt,” Negreanu says. “It’s absolute trash.” But Brunson had a feeling that Alto didn’t have anything either. When Alto bet, Brunson called.

The flop—three communal cards for either player to use in his hand—showed an ace, jack, and ten, giving Brunson a pair of tens. Alto bet again, and even though Brunson’s pair wasn’t much, he decided to play out his hunch. He called. The dealer turned over a two, giving Brunson two pair. Alto looked across the table, trying to read Brunson’s mind. Brunson stared back and noticed the shadows beneath his opponent’s eyes. He had him.

He pushed enough chips into the middle to force Alto to go all in with the rest of his stack. Alto called.

“What’ve you got?” Brunson asked.

Alto flipped over an ace and a jack, giving him the stronger two-pair hand. Brunson showed his ten-deuce and said, “You’ve got me beat.”

But they still hadn’t seen the final card—the “river”—and if that were either a ten or a two, Brunson could still win. The odds against that happening stood at eleven to one.

The dealer flipped the card. Ten of diamonds. Brunson had won the Main Event.

The next year, he was back at the final table, and the winning hand followed an almost identical script. Brunson had been working his opponent, Gary “Bones” Berland, and figured he had him on the ropes. He started with the same exact hand: ten-deuce. The communal cards gave Brunson two pair, and he bet before the dealer turned over the “river.” Berland went all in. The final card showed a ten, giving Brunson a full house and making the back-to-back champion a bona fide poker superstar.

To this day, the ten-deuce is known as the “Doyle Brunson.”

Today Brunson’s home office is full of stacks of documents, photos, and books that pile on his desk, around the floor, and under the window. A documentary crew is working on a film about his life, and he’s been sorting through photos for them. In the middle of it all is his computer, where he keeps Twitter open to interact with fans. Early one afternoon this spring, a new tweet popped up on his screen, and he leaned forward in his chair to see it. “Didn’t @TexDolly teach us that [ace-king] is a drawing hand?” He smiled as he read it.

Somewhere among the papers is an old journal of Brunson’s. He calls it his Book of Miracles, and it contains ten entries, ten moments that he can explain in no other way than divine intervention.

Brunson wasn’t always religious. In 1982 his daughter Doyla died from a heart condition at only eighteen years old, and he left poker for a year. He contemplated suicide. Somewhere in the grief, he started to explore spirituality. He studied Buddhism and Hinduism but eventually came back to the Bible. “I could see,” he explains, “ ‘Well, this thing is true.’ ” One of his old basketball teammates had become a minister and flew to Las Vegas to console Brunson. They prayed together, and soon, many of the poker pros in Vegas were joining them. “I’d see poker games just break up with a million dollars on the table,” he says, “and everybody goes, ‘Well, we gotta go to Bible study.’ ”

Brunson’s miracles range from the unlikely to the truly inexplicable. One recounts a time Louise was driving in rural Montana and her car broke down. Suddenly, out in the middle of nowhere, a man appeared and fixed the vehicle; when Louise turned around to thank him, he had disappeared. “What else could it have been except an angel?” Brunson says.

Another is from 1963. Brunson woke up with a blueberry-size growth on his neck. After a week, it was as big as a lime. His brother had died of melanoma, so Brunson rushed to the hospital. Diagnostic tests confirmed Brunson’s fears, and later, when surgeons operated on him to remove the cancer, they saw that it had spread. They excised everything they could, but they kept finding more. There was no use trying to remove it all; the doctors said he had three months to live. Louise was pregnant with their first child, and she prayed that he’d survive long enough to see the birth.

For all the good fortune recounted in his Book of Miracles, poker doesn’t earn a mention. Brunson never needed luck to win a card game.

They sought a second opinion at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where surgeons proposed a potentially lifesaving procedure but warned that Brunson might die on the operating table. He took the bet. Friends visited and said their goodbyes. Louise prayed more. But when the doctors opened Brunson up, the cancer was nowhere to be found. “I don’t know how to explain it,” he says. “I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but the more things that happened that I did start seeing, I went, ‘Well, good night. Maybe there is some kind of calling—I don’t know.’ ”

Brunson had told Louise that if he got healthy, he’d stop gambling and find a real job to provide for their daughter. Poker was fun, but if he got another chance at life, he would dedicate it to family. He swore to do something respectable.

Once he recovered, though, he felt as if he were living on borrowed time. His brush with death had convinced him that life was too fragile to spend behind a desk. After all, he already knew how to support his family from behind a stack of chips.

He kept playing, and his bets grew more aggressive than ever. The strategy worked—he won 54 games in a row. “It was so uncanny it got to be a joke,” he writes in his memoir. That winning streak paid off all of his medical debt.

Brunson’s Book of Miracles describes other medical marvels, like when Louise survived a uterine tumor, and when Doyla overcame a debilitating spine condition. Yet for all the good fortune recounted in those pages, poker doesn’t earn a mention. Brunson never needed luck to win a card game.

Brunson says he wants to live until he’s 102—his way of honoring the poker hand that bears his name. Around the time he turned 70, though, he realized he’d better get trim if he wanted to last that long. He had grown so heavy that while playing a game in 2003, he struggled to get up from the table. The group he’d been sitting with told him he needed to lose weight, and he replied that he needed to lose a hundred pounds. They asked if he wanted to bet on whether he could do it, and Brunson couldn’t say no to the action. They gave him ten-to-one odds and two years to shed the hundred pounds. Brunson put up $100,000. If he won, he’d be paid back $1 million.

The first year, Brunson didn’t lose an ounce. The following year, months passed, and Brunson still hadn’t lost any weight. But then he went on a diet, and the weight flew off. He might have a shot at that million after all. For the remaining months, he stuck to a strict diet of catfish with Parmesan cheese. With a few weeks to go, the group gathered again. Brunson was down 98 pounds by then, so he offered them a deal. He’d give them 2 percent off if they’d pay him two pounds early. That night, they paid Brunson $980,000, and when they all sat down to play poker after dinner, Brunson lost every cent.

Weight has been a struggle for Brunson for most of his adult life, made worse by mobility challenges that have hounded him ever since he broke his leg in college. During another weight-loss attempt, he tried detoxing at a health center. On his first day there, the staff drew some blood for testing. The next, they drew some more. When they called him into the doctor’s office on the third day, nearly every professional from the clinic was there waiting. “Your cholesterol is less than one hundred,” a doctor explained to him. “We have people down here that eat nothing but raw vegetables and fruit trying to get their cholesterol down to where yours is. And we were just interested in what you eat.”

“I eat everything,” Brunson replied.

The doctors were stunned—on top of everything else, Brunson had also won the genetic lottery. “Your body must be programmed to live one hundred and twenty-five years, as badly as you’ve treated it,” they told him.

Brunson will keep playing as long as that body will let him. If you ask how he’s done it for so long, he won’t talk about betting strategy or even mention poker at all. “I come from a long line of livers,” he’ll tell you. It’s like an old saying of his, one he repeated in the opening credits of the NBC show Poker After Dark: “We don’t stop playing because we get old. We get old because we stop playing.”

And so, at least once a week, the excitement begins anew inside the Bellagio. Brunson enters through the north valet and heads straight to the Legends Room. Just outside, on the walls leading to the administrative offices, hangs a painting of a poem with the title “The Legend of Texas Dolly” written across the top. The canvas has been up long enough that many casino employees don’t know who made it or how it got there. “I know it’s not something we’re going to take down,” says Mike Williams, the Bellagio’s director of poker operations. The poem is decorated with playing cards and a photo of Brunson smiling in his cowboy hat. The final stanza goes like this:

In poker games ’cross this land, by golly

They gun for him, but it’s all pure folly

For tho he holds only ten-deuce

All your chips you’ll turn loose

Because that is the Legend

Of Texas Dolly.

Joe Levin is a writer based in Austin. He was once the top-ranked amateur competitive eater in Texas.

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Original Gambler.” Subscribe today.