Jon Whitfill’s solo gallery show wasn’t off to a great start. It was 2006, and the Lubbock-based artist had just graduated with an MFA from Texas Tech University. He was exhibiting his book wheels—kaleidoscopes of colorful spines and pages—and had dressed for the occasion. A couple walked in, and the husband, not knowing the artist was standing nearby, turned to his wife and said, “Just some asshole destroying books.” They walked out before Whitfill had a chance to explain.

“It was awful,” he says. “Just moments before, I’d been thinking how proud I was, and they were literally the first people that came in. It put a fog over the rest of the show.”

Still, he says he understands why the gallerygoer was miffed. Whitfill, an avid reader and former educator, sometimes feels conflicted about his work.

“I hate the fact that to make these [book wheels], some destruction has to happen,” he says, “but without destruction, creation can’t occur.”

Whitfill believes that turning unwanted relics into art is a far better alternative than them ending up in a landfill. To date, he has salvaged roughly 15,000 discarded books. Libraries often reach out to him, wanting to off-load titles they’ve removed to make room for more books, more seating, or, more often than not, more computers. Sometimes, Whitfill shows up at his studio in the tiny town of Slaton to find that people have left boxes at his front door. The first book wheel Whitfill made was composed of old romance novels he came across during a demolition project.

“The cool thing about pulp fiction is that they typically dye the edges of the page,” he says. “I was taking a break and just started putting all the colors together and was inspired to make a few paperback romance-novel color wheels.”

Left: Jon Whitfill with his book wheels. Courtesy of Jon Whitfill

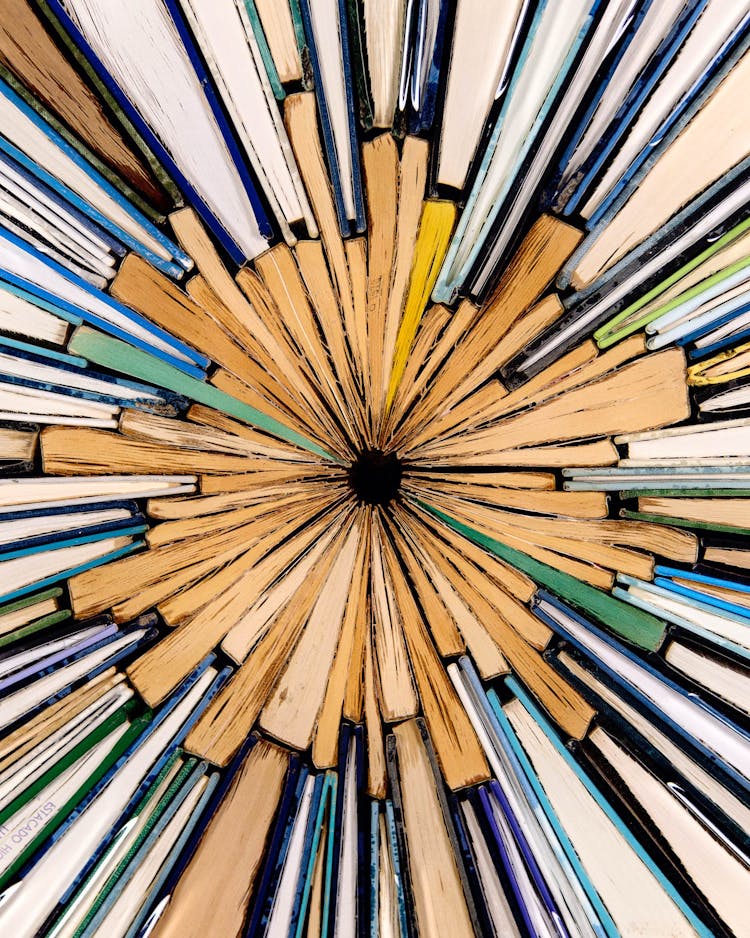

Top: A close-up of one of Whitfill’s book wheels. Courtesy of Jon Whitfill

His process has evolved as he’s gotten new tools and tried different techniques. As a former high school science teacher, Whitfill says it’s all part of the scientific method. Trial and error goes into each work: it can take multiple tries to shape the designs to his liking; books absorb resin differently depending on age and paper type. As a result, no two wheels are exactly the same.

The book wheels can cost anywhere between $2,000 and $8,000, depending on size, and take about a month to make. The majority of that time is dedicated to planning and preservation. Whitfill starts by removing pages from the spine to create a wedge, then uses a band saw to create the desired depth and fits the wedges together to form a circle. What follows is roughly fifteen thin layers of resin. Although Whitfill can’t use every part of a book in a single wheel, nothing goes to waste.

“I take the pages that have to be removed to turn a book from a square into a triangle and restack those pages into boxes, then cut them and resin the end to basically make new books,” he explains. Along the way, he sets aside pages with interesting illustrations or text that intrigues him for other types of art, such as collages. (He’s also known for his metal sphere sculptures.)

There are some things Whitfill won’t do, such as buy books to fit a particular theme or color palette, even if it means saying no to a client’s request. “Sometimes I’ve done a commission for authors who want to incorporate their own pieces, so they might go to a garage sale or whatever and bring me a box of other books to use alongside theirs, but I don’t go to Barnes and Noble. I won’t take something that still has life left in it,” he says, noting that “parameters breed creativity.”

Whitfill also can’t bring himself to cut up anything from his favorite genre, science fiction, because he says so many of the predictions authors made back then came true—a lesson in what he calls “reverse history.” While any salvaged sci-fi novels go directly into Whitfill’s personal library, he feels certain texts are too precious not to share with others.

When he received thousands of patent books containing the intricacies of various inventions, he felt “weird” about keeping those all to himself. He’s since shipped roughly 250 across the country and the world to other artists, inviting them to make pieces based on the books to be exhibited in an ongoing series of shows called “Patent Pending.”

“It’s a way to get these out into other artists’ hands and see if they can be inspired by them, too,” he says. Knowledge sharing is something Whitfill thinks about a lot. He was recently commissioned by his alma mater, Texas Tech, to design several large-scale works out of old law books for the campus law library. He asked the librarians if physical copies were being preserved elsewhere. Their response? It’s all digital now.

“That scares the hell out of me,” Whitfill says. “What is being lost that we don’t even know about? Who’s going through to make sure each of those books even has a digital imprint? What we need is a bunch of people out there going, ‘I love books; let me just go through every one and make sure we don’t miss anything.’ ”

Knowledge lost is never a good thing, Whitfill says, whether it’s due to digitization or a crusade to ban certain books. “You need to know what’s going on,” he says. “You need to have the opportunity to make your own decision and not just take someone else’s rote ideas for your own.”

Whitfill welcomes different opinions when it comes to both politics and his art. He says the lion’s share of feedback he’s received has been positive, but when people are critical, it’s usually because they’re concerned about where the books came from—“an incredibly valid question,” Whitfill says.

“Sometimes I need to explain that these were detritus. Yes, it could be read again, but it was on its last journey when it got to me,” he says. “Books are beautiful objects on their own accord, but getting to see them in a way that you may never see them also has an appeal. Maybe it wasn’t their intended purpose, but it can still bring you joy.”