Di Poi, C., Brodu, N., Gazeau, F., Pernet, F. 2022. Life-history traits in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas are robust to ocean acidification under two thermal regimes. ICES Journal of Marine Science 79, 2614-2629. DOI: 10.1093/icesjms/fsac195

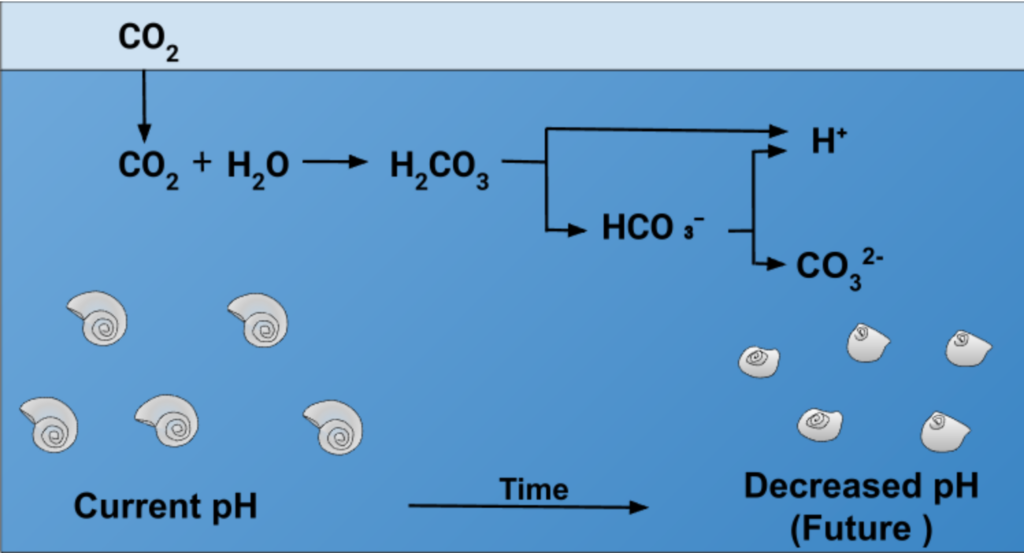

Global climate change, caused by high levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, affects not only organisms on land, but also those in the ocean. Not only does rising CO2 cause higher temperatures, but carbon dioxide also causes changes in seawater properties such as pH and the availability of necessary chemical ions. When carbon dioxide enters the ocean it pulls apart, releasing hydrogen ions that decrease the ocean’s pH, increasing how acidic the water is (ocean acidification). In addition, this process reduces the number of carbonate ions in the ocean. Carbonate and calcium ions are used by many marine animals that form calcium carbonate shells, like oysters. Therefore, ocean acidification and ocean warming could have negative effects on these important species.

Researchers from France set out to explore what happens to adult and larval Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) exposed to ocean acidification, ocean warming, or both. Because these animals live in coastal environments, where temperature and pH can fluctuate naturally, the researchers also used fluctuating pH and temperature conditions in tanks for 35 days. Four treatments were conducted – the controls, at normal temperature and pH, the ocean acidification condition, the ocean warming condition, and ocean acidification plus warming. After 35 days the adult oysters in each treatment were spawned to produce offspring, and then the researchers measured growth, feeding rate, egg and sperm quality, and a number of neurochemical profiles.

Offspring, or larval oysters, in the acidified and warming treatments were exposed to the same conditions as their parents. Larvae from the control and acidification plus warming treatments were either raised in the same conditions as their parents, or transplanted to the opposite condition (i.e. control to acidification plus warming, acidification plus warming to control), to investigate whether or not there were any effects of parental treatment on how well larvae did under different conditions. After two days of allowing the larvae to grow the researchers then measured the hatching rate, shell height, shell calcification rate, swimming behavior, and the number of larvae that reached a specific stage of development.

Surprisingly, the researchers found little effect of ocean acidification plus warming together on either adult or larval oysters. Exposure to acidification alone reduced the growth rate of adults and activated a neurological system associated with serotonin – however, those effects weren’t seen in the ocean acidification plus warming treatment, implying that warming offset effects of acidification. Exposure to acidification also reduced the shell length and body weight of adult oysters, likely because of reduced shell formation, but again the ocean acidification plus warming treatment didn’t show this effect. There were also no direct effects on the larvae.

The good news is that this data suggests that the Pacific oyster is resilient to near future ocean acidification and warming conditions. However, it’s important to note that the pH and temperature conditions used in this study were within the range that oysters might normally experience in their natural environment, since they live close to shore and can see large shifts throughout the day. Future studies should look at the natural fluctuations in oyster environments and how they will change with increased warming and acidification.

I’m a PhD student in Oceanography at the University of Connecticut, Avery Point. My current research interests involve microplastics and their effects on marine suspension feeding bivalves, and biological solutions to the issue of microplastics. Prior to grad school I received my B.S in Biology from Gettysburg College, and worked for the U.S Geological Survey before spending two years at a remote salmon hatchery in Alaska. Most of my free time is spent at the gym, fostering cats for a local rescue, and trying to find the best cold brew in southeastern CT.