This story is part of the Grist series Flood. Retreat. Repeat, an exploration of how communities are changing before, during, and after managed retreat.

Linda Worsley had been trying to get back to her hometown of Princeville, North Carolina, for almost six years. In 2016, Hurricane Matthew overwhelmed the banks of the Tar River and submerged the town under more than 10 feet of water, destroying Worsley’s house and nearly 500 others. Worsley fled with her family, but she returned without one: Her mother, father, and husband all passed away before they could move back. Many of her closest friends had also died or moved elsewhere during her period of exile.

Worsley and I sat on the porch of her parents’ house, less than half a mile from the banks of the Tar River, one hot afternoon in early June. I noticed the sounds of North Carolina’s swampy coastal plain region: huge wasps buzzing around us (Worsley doesn’t mind them), twittering birds darting around the porch, and a short freight train chugging past us, carrying scrap metal. Worsley, 72, mostly notices what’s gone silent. When she sits on the porch, the absence of passing cars and neighbors’ voices reminds her of how much she has lost; when she leaves the house and drives through the streets of Princeville, the rows of abandoned houses remind her of how much the small town of 2,000 has changed.

“The caring is gone,” Worsley said. “In a way I’m glad to be back here, and in a way I’m not.”

The flood caused by Hurricane Matthew was at least the 10th major flood in Princeville’s 150-year history, and the second in as many decades. It devastated the town, displacing hundreds of people and wiping away entire blocks. Since then, longtime residents like Worsley have been struggling to return and rebuild, waiting on the aid money the federal government is supposed to provide in the aftermath of natural disasters. Meanwhile, the houses they left behind have begun to rot and sag, their white slats turning fuzzy and green with mold.

The cost of repairing their damaged houses made it impossible for many of Worsley’s neighbors to return until they received federal aid, but thanks to the government’s convoluted bureaucracy, much of that money is still in limbo. Some people sold their destroyed properties for pennies on the dollar. Many just walked away, renting in nearby cities like Tarboro, Rocky Mount, and Pinetops. The storm had exiled them from the town where their families had lived since the aftermath of the Civil War, when a group of emancipated Black people founded the town on abandoned land.

“It’s God’s will, it’s not my will, and we just have to accept that,” Worsley said. “I have been gone from here up until last Monday. No way I could have foreseen that I’ll be gone that long.”

While she waited for federal officials to process her aid application in the years after Hurricane Matthew, Worsley spent tens of thousands of dollars renting a series of apartments in and around Tarboro. This spring, five years after her application was submitted, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, agreed to buy her a new manufactured home and set it up on her family property. When I visited the Worsley family’s three-acre plot in June, the home hadn’t yet arrived. Instead, a storage unit containing all of Worsley’s belongings sat next to a clearing in the yard, full of knickknacks and family heirlooms. Worsley didn’t know when she’d unpack.

Dozens of other places around the country have suffered the same fate as Princeville, their communities emptied out and scattered by natural disasters fueled by climate change. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, which monitors involuntary movements around the world, more than 200 flood events have displaced half a million Americans since 2008. In the aftermath of these disasters, residents in ruined towns and neighborhoods have confronted an agonizing choice: return to the place they know, or move somewhere safer?

In Princeville, what’s at stake is not just one town’s survival but a unique window into American history: Princeville is the oldest community in the United States chartered by Black people. In an effort to safeguard this history, several arms of the state and federal government have promised to invest millions of dollars to protect the town, which is still more than 90 percent Black, from floods. The wide variety of strategies deployed offer a preview of the ways the government plans on helping communities adapt to climate-fueled disasters in the future. The Army Corps of Engineers has promised to build a levee that would protect against floods brought on by storms like Hurricane Matthew, while FEMA has offered to buy out flood-prone homes and relocate residents. The state government has launched a third campaign to build a new version of Princeville on higher ground.

But even as the government moves to protect Princeville, the hundreds of people who have already died or moved away have left holes in the town’s social fabric. Princeville is caught between rebuilding and retreating, unable to bring all its residents back but also unable to convince them all to move somewhere safer and more stable. The town’s decline is a testament to just how much history is at risk in an era of accelerating climate change, as well as an object lesson in the contradictions of climate adaptation. Disasters like those brought by Hurricane Matthew don’t lead to complete rebuilds or complete retreats. Instead they condemn towns like Princeville to a kind of indefinite limbo, trapping them between the future and the past.

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, millions of formerly enslaved Americans found themselves in a world that was profoundly changed. The Union’s 1865 victory and the passage of the Constitution’s 13th Amendment had brought an end to chattel slavery and thrown the South’s plantation economy into turmoil. But as efforts to redistribute Southern land to Black Americans soon stalled out, most stayed within a few miles of the estates where they had once been in bondage.

In the heart of North Carolina’s plantation country, a group of these freedmen congregated on the banks of the sluggish Tar River after the war, forming a settlement across the river from the town of Tarboro. At first the freedmen had no legal right to the Edgecombe County tract they were living on, but the land was too flood-prone to support cotton, so the white planters who owned it eventually sold it off to them at cut-rate prices. By 1880, the settlement boasted around 400 residents, many of whom worked as day laborers, laundresses, or in other occupations that kept them “only a step away from slavery,” in the words of North Carolina State University historian Joe Mobley. But there were also blacksmiths, farmers, teachers, and two local leaders who were among the state’s earliest Black legislators.

It was around that time that residents began campaigning to incorporate an independent town named after one of its founders, a carpenter named Turner Prince. When the state legislature formally recognized Princeville in 1885, it became the first municipality in the postbellum United States to be chartered by formerly enslaved people.

From the beginning, Princeville’s fortunes were intertwined with the caprices of the Tar River, which flooded the town every few years. Floodwaters would seep through pipes, contaminating drinking water, and the puddles that accreted by the banks of the river attracted hordes of mosquitoes. When the Tar crested its banks, residents would watch their homes and stores wash away. Not even those that were built on stilts were safe. A local legend holds that during the great flood of 1919, a less-than-honorable mayor was seen fleeing downriver on a rowboat, clutching a chest full of money purloined from the town treasury.

In 1958, 75 years after its founding, Princeville was still vulnerable to every flood event. After the town was submerged for the eighth time in its short history that year, local leaders began a concerted and ultimately successful campaign to lobby the federal Army Corps of Engineers to build a levee along the Tar River.

When the Corps completed the levee in 1967, it was as though the town had been reborn. The levee, a grassy rampart that stretched three miles along the river bank, rose a steep 37 feet at the water’s edge and sloped gently back down toward the town settlement. It was almost unthinkable that the water would ever rise high enough to flow over the rampart. An entire generation of residents grew up without fear of flooding, and dozens of businesses sprung up, many of them owned by locals. There were convenience stores, mills, a blacksmith, an auto shop, and a psychic by the name of Madam Rose.

“We were a very small town, but it was quite serene,” recalled Delores Porter, who grew up just off Main Street, near the spot where Princeville was founded. “We didn’t have to worry about being worried. We could keep our doors unlocked at all times, and we just had fun, and you knew everybody. I always say that we were poor, but we didn’t know we were poor.”

The peace was not to last. Princeville’s decades-long reprieve from flooding came to an abrupt end in September 1999, when Hurricane Floyd made landfall in North Carolina as a Category 3 storm. Though the levee was built to withstand even strong hurricanes like Floyd, the timing could not have been worse. Ten days earlier, the smaller Hurricane Dennis had passed over North Carolina not once but twice, soaking the ground and raising the water level in rivers and lakes. The rainfall from Floyd swelled the Tar River to almost 42 feet above its normal flow, high enough to overtop the levee.

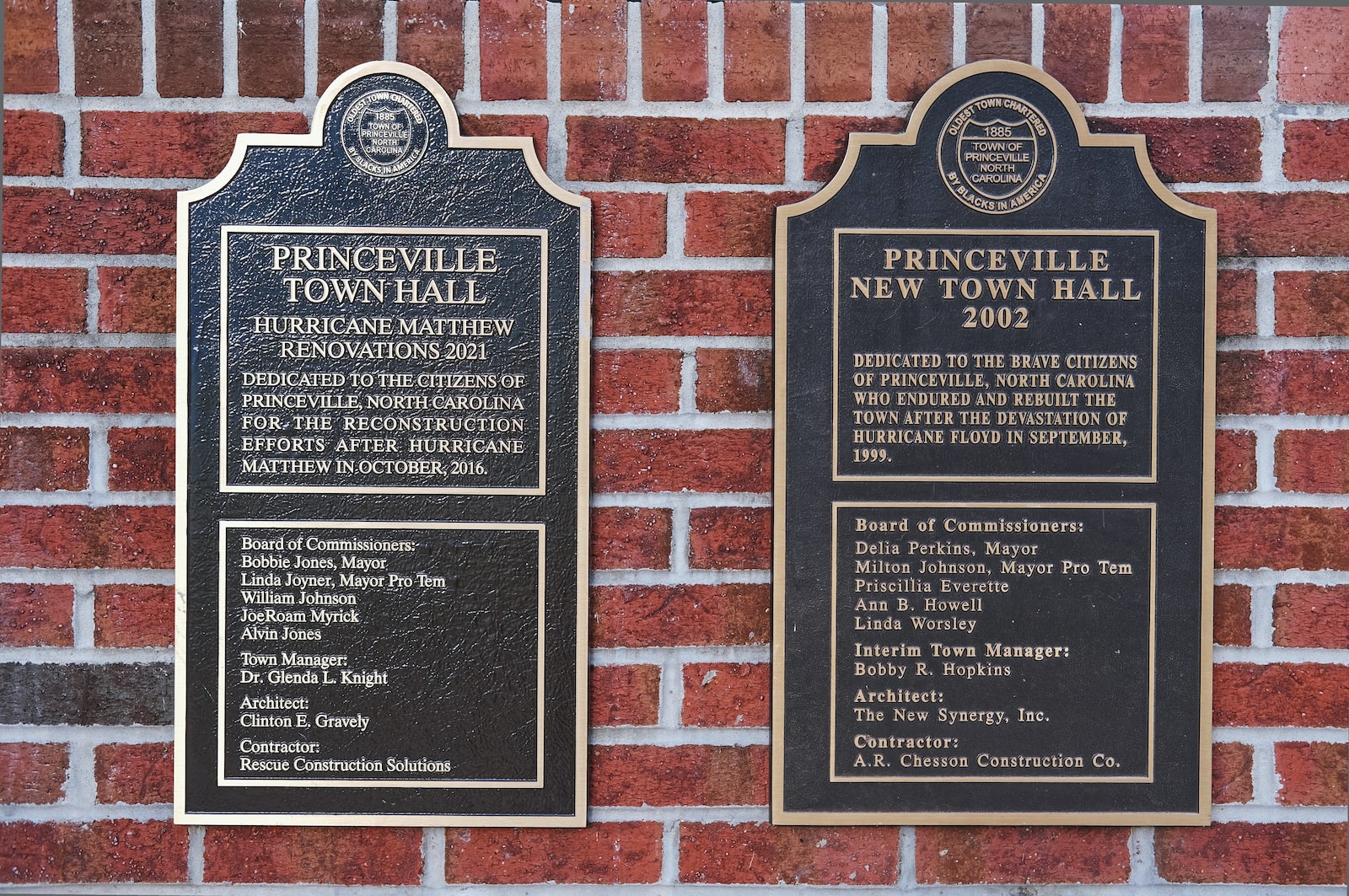

The residents of Princeville rushed to fortify the Army Corps levee with makeshift stacks of sandbags, to no avail: The floodwaters soon spilled over and inundated the town, pooling in the low-lying basin of land. When the flood reached its peak, only the treetops were visible above the water, along with a few church steeples. The water knocked down rows of brick houses along Main Street, destabilized the Reconstruction-era town hall, and squished dozens of mobile homes like soda cans. (Madame Rose’s house also flooded, casting doubt on her psychic powers.)

Within days, the town’s plight attracted national attention. Emergency response teams from the county, state, and federal government arrived, along with then-Congresswoman Eva Clayton, then-Governor Jim Hunt, and civil rights leaders like Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson. Prince and Queen Latifah sent donations. Even President Bill Clinton turned up in town, later signing an executive order to assist Princeville’s recovery.

Before the recovery could start, though, Princeville had to make a choice. FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers had approached the town’s mayor, Delia Perkins, with two contradictory offers. The Corps offered to fortify its levee, raising the height of its walls and fixing flaws in the old structure, such as a divot by the railroad tracks where water could rush through. At the same time, FEMA offered to buy out a large share of the homes in Princeville, giving residents the resources to move somewhere safer while simultaneously depopulating the town. Perkins and her colleagues on the town board could accept one offer or the other, but not both.

This was thanks to a Reagan-era regulation that required federal agencies like the Corps to conduct cost-benefit analysis for every project, forcing officials to prove that the financial upside of a project outweighed what it would cost. If FEMA bought out the town’s residents, there would be so few houses left that the Corps would not be able to justify building a levee. The federal government could only give so much money to an impoverished town like Princeville, where the median household income today is still around $33,000, less than half the national figure.

The four-member town board soon deadlocked on which offer to take, with two members arguing that residents deserved the chance to move somewhere safer and the other two arguing that it was wrong to give up on Princeville’s legacy. Mayor Perkins held the tie-breaking vote, and she had been opposed to buyouts from the beginning. Princeville would stay put.

“I did not think the buyout was a good idea,” Perkins told me. “Participating in the buyout would mean leaving all our history behind.”

So the displaced residents of Princeville moved back, reassured by the Army Corps’ promise to repair the levee. FEMA distributed aid and helped rebuild homes, but it didn’t buy anyone out. Some of those who were more concerned about flooding shuffled away from the historic center to the outskirts of town, where the housing stock was newer and less vulnerable, while others erected new brick houses and trailer homes on land that had just flooded. Slowly, life trickled back into Princeville. Some of the businesses that shuttered after the storm never reopened, but almost everyone returned. Most people weren’t concerned about the next flood: Experts had said that Hurricane Floyd was a hundred-year storm, the kind that hits just once a century, and the Army Corps had vowed to start work on the new levee within a few years.

Neither of those assumptions turned out to be true. As the years passed, the Corps made little progress on the levee project, and its communications to Princeville’s leaders became less frequent. Princeville went through several mayors and city managers over the same period, and some of the new leaders neglected to pursue the levee repairs. The result was that it took more than a decade for the Corps to identify a few viable options for repairing the levee, and even longer to actually begin conducting engineering studies for the structure. (In response to questions from Grist, a spokesperson for the Army Corps of Engineers attributed the delays to the difficulty of designing a project that met federal cost-benefit regulations.)

In the spring of 2016, more than 15 years after Hurricane Floyd, the Army Corps of Engineers returned to Princeville to present residents with its final levee study. The results were alarming: Not only was the previous levee weaker than the Corps had thought, but it also contained numerous structural defects that would render Princeville vulnerable even to smaller storms than Floyd. The town needed a brand-new levee. Without it, the report said, “each occurrence of flooding would bring another round of suffering and hardship to the community.”

That prophecy would be fulfilled far sooner than anyone thought.

Six months later, Linda Worsley was at home cooking a pot of pig’s feet. Hurricane Matthew had just passed over North Carolina, but it hadn’t caused any significant damage to Princeville, so Worsley was resting easy. Shortly after nightfall, though, she got a phone call from her mother, who sounded frantic. She told Worsley that the Tar River was going to crest its banks and breach the town levee again, just like it had during Hurricane Floyd 17 years earlier. Worsley looked outside. Sure enough, there was already water rising through a ditch in her yard. She showed her husband, who said it wasn’t worth worrying about: Floyd had been a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Worsley was still scarred from her experience escaping Princeville during the last flood and wasn’t going to take any chances. She left the house and drove across the river to Tarboro, where she booked a room at the Quality Inn just to be safe. Her husband stayed at home to finish cooking, and by the next morning the floodwaters had reached the Worsleys’ doorstep, making it impossible for him to drive out. He climbed up to the roof of the house and hollered until some neighbors who ran an auto body shop approached the area in a cherry-picker truck and scooped him off the roof.

To many people in Princeville, it seemed like history was repeating itself. Meteorologists had called Hurricane Floyd a “100-year storm,” which made it sound like it would only happen once in a lifetime, but in fact the term only meant that the storm had about a 1 percent chance of happening each year. Matthew was another 100-year storm in less than 20 years. This time, instead of overtopping the levee, the floodwaters rushed in through a gap where the railroad tracks went through, sweeping away Worsley’s home and dozens of others. The houses that remained were so sodden and moldy they could barely stand up. In the weeks that followed, the town’s residents scattered in all directions, renting rooms in Tarboro or taking up residence in trailer parks around the county. Some moved in with relatives farther away in larger cities like Fayetteville and Raleigh.

“The first time, I could not believe it. It was like something out of a movie,” Worsley said of living through Hurricanes Floyd and Matthew. “The second time I said, ‘Well, what will be will be.’” People in Princeville had told themselves that another storm like Floyd was impossible, but in fact such monster hurricanes are becoming more common in an era of accelerating climate change. As the ocean warms, it provides more fuel for tropical cyclones as they barrel toward the mainland United States, helping storms like Matthew gather strength faster and maintain that strength longer after they make landfall. Warmer air can also retain more moisture, which makes rainstorms even wetter. Princeville had always struggled against the river, but these two climatic shifts had helped to make devastating floods much more likely.

After Matthew, Princeville’s people were again presented with a choice to stay put or leave, this time with the knowledge that storms like Floyd could come more than once in a lifetime. The Army Corps had just completed its plan for a new levee to protect Princeville from more rounds of suffering, and the only remaining barrier to building it was securing funding from Congress. No one knew how long that would take. At the same time, FEMA was offering millions of dollars in recovery money, and representatives from the federal and state governments were urging the town’s leaders to consider buyouts.

Bobbie Jones had been elected mayor two years before Matthew hit. A schoolteacher who had been born in Princeville but spent most of his adulthood elsewhere, Jones moved back after Floyd to help revitalize the town. He opposed buyouts, and in his early conversations with FEMA officials he insisted that his friends and neighbors wouldn’t take them. They would take money to rebuild destroyed homes, or to elevate homes off the ground, but not to leave.

“I’m totally anti-buyout because of the significance of the town of Princeville,” Jones told me, ”and because we’re already operating on a small budget of less than a million dollars. Every time you take away a home and you can’t replace it with a home, that tax base decreases.”

After Hurricane Matthew struck in 2016, though, the board overruled Jones, voting to allow residents to decide for themselves whether they’d take a buyout. The experience of a second flood had shown the board members that the risks facing Princeville were far greater than they had thought. They felt an obligation to let people leave if they wanted to. A few months later, the state government pitched the town on a second buyout program that would target a specific area around Princeville’s historic main center, the area that faced the greatest danger from floods. Most residents felt the same way as Jones and wanted to return to their homes if possible, but a few dozen residents enrolled in the state or FEMA buyouts. It seemed like Princeville’s social ties were finally starting to fray.

At the same time, the state government approached Princeville about yet another adaptation project, one that would allow the town to move to higher ground in a more concentrated way. The state would purchase a 53-acre tract of vacant land near housing on the outskirts of town. Essential town services like the fire station would be relocated to the new tract, and the state would also help build a few new affordable housing units. The idea was to relocate Princeville entirely out of harm’s way, but Jones managed to negotiate something different: The state would help build the new subdivision for Princeville, but the town’s longtime residents would all stay put, and the town hall would be rebuilt on the original historic land as well. A few years later, the state bought another 88-acre tract and sketched out a mixed-use housing development for that land, and Princeville received another million dollars from FEMA to help build it. Despite Jones’s insistence that Princeville is not moving, FEMA’s grant paperwork refers to the project as a “relocation.”

“The vision we have is for visitors to come in to see the historical area, but also be able to spend dollars and cents in the new commercial area,” Jones told me. “We just don’t want to recover. We want to flourish.”

Each one of these adaptation actions made sense on its own, but the big picture revealed contradictions. FEMA had doled out grant money to rebuild homes, but it was also funding buyouts to help people leave. The state of North Carolina was doing the same thing, even as money from another federal grant program was paying to help the town move to higher ground. Then, in 2020 Congress gave money to the Army Corps to build a new levee and protect the town’s core, even though other government agencies were working to depopulate that area. The federal officials who funded these various projects were all trying to respond to Princeville’s needs, but different residents had different visions for the future — some wanted to stay, some wanted to leave, some wanted to shift to higher ground, and still others were just trying to make ends meet.

The federal and state governments had the money and the will to save Princeville, but no one agreed on how to save it. Did saving the town mean fortifying the land that Turner Prince and his fellow freedmen had settled, or did it mean giving vulnerable residents a chance to move somewhere else? And who got to decide which path the town took?

“After Floyd, it was seen much more as ‘one or the other’ between the [levee] and the buyouts, but the situation is a little bit more complicated this time around,” said Amanda Martin, the chief resilience officer in the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency, who has led the state’s recovery efforts in Princeville. According to Martin, the fragmented nature of the disaster recovery system has made it impossible to coordinate a unified response to Hurricane Matthew — even now, six years after the fact. The result is that Princeville has become the rope in a game of tug-of-war, with federal and state agencies pulling the town in different directions.

“These decisions are being made by so many different people, with so many different funding sources,” Martin said. ”We don’t have the tools or the framework to make them as interdependent kinds of decisions. No one’s able to make a decision that’s informed by anything other than what they have right in front of them.”

By the time the sixth anniversary of Hurricane Matthew comes around next month, Linda Worsley will be living in her own home in Princeville again, having finally reached the end of her road to recovery. Her new manufactured home sits nine feet off the ground on wooden pilings, a few feet higher than the floodwaters from Floyd and Matthew.

Princeville itself still has a long way to go. As another hurricane season reaches its peak, the town is more vulnerable than ever. The Army Corps of Engineers still has not begun construction on the new levee. Corps officials discovered last year that their proposed design would push water toward Tarboro in the event of a major flood. The agency went back to the drawing board and expects to present Princeville officials with a new plan next month.

The Corps declined to provide Grist with an updated timeline for the levee’s completion but noted that, “due to a variety of factors like inflation and cost,” it is “unlikely” that the money appropriated by Congress would be sufficient to finish the project. “If there was a simple solution to this problem, it would have been identified by now,” said a Corps spokesperson. “We understand the frustrations.”

In June, as I drove through the streets of the town’s historic center, I found myself surrounded by an eerie silence. There were four or five houses on each block, but only one or two of them showed signs of life. The others had facades stained green with mold, or gaping holes where their doors should have been. Some homes looked like they were in good condition until I got up to the doorstep and saw sagging columns on the porch or shattered glass in the windows. On other blocks, the lots were vacant and overgrown, untouched since Hurricane Floyd more than 20 years earlier.

A sign at the entrance to Princeville’s town hall features a picture of Jones, who was reelected mayor earlier this year, along with a caption that reads, “I could never be completely satisfied until all our citizens are back home.” The residents who own empty homes and abandoned lots, meanwhile, are still out there; indeed, many of them live just a few miles away, but the myriad delays in the recovery process have made it impossible for them to return. FEMA’s grant money first has to be disbursed to state governments, which then have to work out recovery plans with county governments, which then have to take applications from residents, which then have to go back up the paper chain so FEMA can approve them. The result is that many Princeville residents, both those who wanted to rebuild and those who wanted to take buyouts, are still waiting for their money to arrive.

Delores Porter is one such resident in exile. She spent most of her life living right off Main Street in Princeville, and she rebuilt within a year after Hurricane Floyd. But since Matthew hit, Porter has been living across the river in Tarboro, working at a Christian printing shop and driving over to check on her old property whenever she can. Porter applied for recovery funding from FEMA to rebuild her home in 2016. Because her house was in a flood zone, she could not rebuild it as it had been. Like Worsley, she would have to elevate it many feet in the air — a tough decision, given that her husband uses a wheelchair. Almost six years have passed since she first applied, but she still hasn’t received any money from FEMA. She isn’t sure she ever will and has all but given up on trying to pursue her application.

“Why should I rush to get something done and rebuild, and then there’s a flood and I lose everything?” she said. “I’m holding out as long as I can, and my land is still my land, and maybe one day I’ll make it back.” Porter is happy that Worsley returned to Princeville after so many years, but she doesn’t know if she’ll be joining her friend any time soon.

Joann Bellamy moved further away to Fayetteville, where her son lives. She applied for a buyout from a state program after Matthew, only to be told that her flooded home wasn’t in the subsection of town the state had identified for buyouts. She’s still hoping to secure one from FEMA, but she isn’t optimistic.

“They are not doing enough for the people, rebuilding folks’ houses and helping them out,” Bellamy said. “I signed up for the buyout, we did all the paperwork, they kept telling us we needed this, and we needed that, and we couldn’t get no help — we were in the flood zone, but we weren’t in the district.”

In response to questions from Grist, a FEMA spokesperson said that the agency has received around a hundred applications for buyouts and home elevations in Princeville since Hurricane Matthew. Eight buyouts have been completed, plus Worsley’s elevation. The rest of the repair projects are still pending.

Stories like Porter’s and Bellamy’s paint a grim picture of Princeville’s future, at least in its historic center. Some, like Bellamy, will continue to move away out of frustration with the bureaucratic delays. The most dedicated — and the luckiest — may follow in Worsley’s footsteps and return to their original homes or build new houses that are elevated off the ground. But in the absence of a new levee, the returning residents will be just as vulnerable as they were before Matthew.

To the extent that Princeville has a future, that future may be in the new elevated acreage that the federal and state governments are working to develop. In one sense, the history of the town has already seen a slow migration away from the Tar River, with new development shifting back from the levee and toward the high ground that Princeville is now building on. Worsley and Mayor Jones see this shift as a means to an end, a way of generating tax revenue to protect the old Princeville, but in another generation this new Princeville might be all that remains.

Not everyone sees this as a bad thing. The day after I visited Worsley, I took a drive around town with Calvin Adkins, a lifelong Princeville resident. Adkins has served in what seems like every aspect of local civic life: He’s been a newspaper reporter, a town clerk, a liaison for FEMA’s recovery efforts, and several other things besides. As we circled around the historic center of town, he seemed to remember who lived on every lot, whether occupied or vacant, recalling a childhood memory from just about every intersection.

Adkins grew up in the historic center of Princeville, but he moved to one of the newer subdivisions on the outskirts after Hurricane Floyd. Even there, he said, he saw some flooding during Hurricane Matthew. The flooding led him to conclude that nowhere in Princeville was safe, which is why he’s trying to get FEMA to offer him a buyout on his new house. He wants to move somewhere else in the county, leaving his hometown behind.

“I don’t want to go through another flood. The anticipation of knowing or not knowing if it’s going to flood, it’s devastating” Adkins said. “That doesn’t take away from my love for Princeville. I love Princeville, but I gotta love me better.”

Adkins isn’t holding out hope that the long-promised levee can save Princeville. He understands why people like Worsley and Jones want to stay, but he doesn’t think it’ll ever be safe. The past might have limited Princeville’s founders to dangerous, low-lying land that white planters did not want, but, as Adkins sees it, the future is on higher ground.

“What do you think Turner Prince would do?” he asked. “Do you think Turner Prince would allow his people to stay in a flooded area, given the chance to move? My answer would be no. He’d say, ‘As sacred as those grounds are, we can’t stay here.’”