Update: In April 2024, the U.S. Department of the Interior under the Biden administration announced rules codifying protections for the existing 13.3 million acres of Special Areas in the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska, limiting future oil and gas leasing and industrial development. Additionally, the Bureau of Land Management announced a process will soon start to consider expanding or adding additional Special Areas within the NPR–A. The decision did not affect the Willow project, a major new oil development that the Biden administration approved in 2023, which lies just east of the areas protected in the 2024 announcement.

Originally published March 31, 2024; updated April 22, 2024. From the Spring 2024 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

The largest single tract of wild public land in America, a landscape so vast and diverse it defies superlatives, is known by a bland and somewhat misleading four-letter acronym: NPR-A.

While the NPR-A, or National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska, does have oil beneath it, the 23-million-acre expanse is also arguably the most important wetland habitat complex in the Circumpolar Arctic for birds—the breeding, nesting, molting, and premigratory staging grounds for several million birds every year.

Stan Senner, Audubon’s former vice president for bird conservation and the former director of Audubon Alaska, says it is undeniably spectacular.

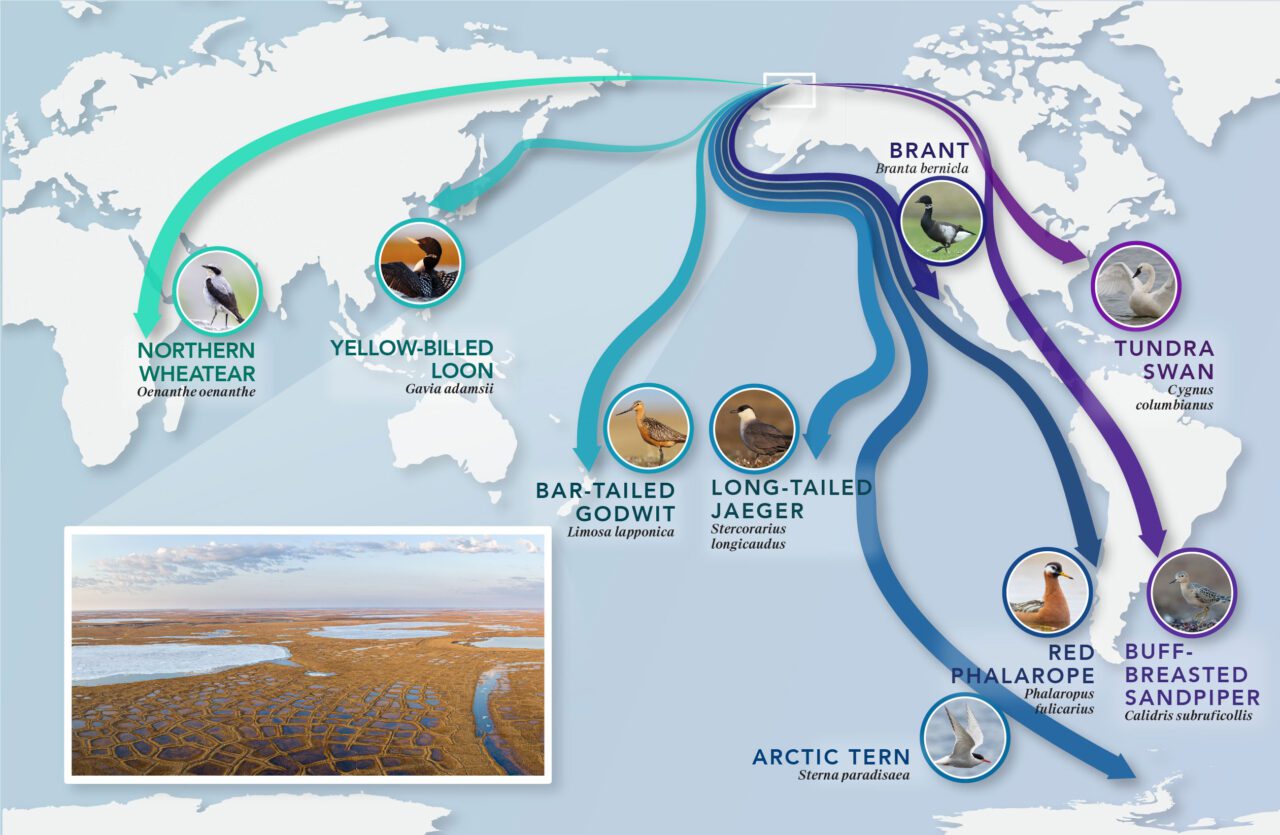

“The reserve has big numbers of birds coming from seven different continents to nest,” says Senner. “Waterbirds, which include ducks and geese, loons, all of the shorebirds, gulls, terns, jaegers, they’re coming in the hundreds of thousands, and millions.… They’re at densities and diversities that are not found anywhere else in the Alaskan Arctic, and very high relative to the entire global Arctic.”

Indeed the entire Alaska North Slope is abundant with wildlife—and oil. Retired wildlife biologist and former Audubon Alaska senior scientist John Schoen has seen that dichotomy firsthand. As a young man, Schoen worked as a bear biologist and pilot for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in the 1970s, flying transects in a De Havilland Beaver floatplane with a big camera to survey the Porcupine Caribou Herd.

“I’d been to Africa, and I’d seen a million wildebeests from the air,” Schoen says, “but nothing, nothing like this.”

Schoen was similarly amazed on the same trip by the size and scope of Prudhoe Bay, the largest active oilfield in North America.

“I couldn’t believe how intensive the development was,” he says. “It just went on and on, the spiderweb of roads and pipelines and infrastructure.”

NPR-A was established in the western area of the North Slope by an executive order from President Warren G. Harding in 1923 to ensure energy reserves for the U.S. Navy as it transitioned from coal to oil. In 1976, Congress transferred management to the Department of the Interior, continuing subsurface oil and gas exploration, but also directing the Bureau of Land Management to provide “maximum protection” for surface areas with “significant subsistence, recreational, fish and wildlife, historical or scenic values.”

U.S. Fish and Wildlife surveys in the reserve led to the establishment of “Special Areas”—a land management designation unique to Alaska that’s placed on habitat of the most value for wildlife.

Special Areas of the National Petroleum Reserve

Peard Bay Special Area

At 107,000 acres, the Peard Bay coastline and wetland complex is vital for polar bears and three species of ice seals, and increasingly this place serves as a haul-out area for thousands of walrus to rest as late-summer sea ice continues to recede earlier and farther north. Peard Bay is characterized by thousands of small thermokarst or thaw lakes—depressions formed by thawing permafrost that provide important habitat for nesting loons, waterfowl, and shorebirds. It’s a high-density nesting area for Yellow-billed, Pacific, and Red-throated Loons, as well as Spectacled and King Eiders, Sabine’s Gulls, Long-tailed Ducks, and Red Phalaropes.

Teshekpuk Lake Special Area

Teshekpuk (Inupiaq for “great enclosed water”) Lake and the surrounding wetlands complex is one of the most important places in the entire Arctic for waterbirds. In summer around 100,000 geese arrive—including Greater White-fronted, Snow, and Cackling Geese, as well as Brant—seeking food and safety from predators as they molt and become flightless. The spongy wetlands are the breeding home of globally significant numbers of shorebirds such as Black-bellied Plover, Semipalmated Sandpiper, and Dunlin. All four of the world’s eider species—King, Common, Spectacled, and Steller’s (the latter two protected under the federal Endangered Species Act)—nest here, as well as Long-tailed Ducks, Northern Pintails, and Yellow-billed, Pacific, and Red-throated Loons. In March 2023, the Biden Administration approved the Willow oil drilling project, which would bring drill pads, roads, and pipelines to the eastern edge of the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area.

Kasegaluk Lagoon Special Area

The shallow waters and barrier islands of the 97,000-acre Kasegaluk (Inupiaq for “spotted seal place”) Lagoon Special Area provide important denning and feeding habitat for polar bears and a haul-out area for walrus. Pods of beluga whales molt by scraping away their outer layer of white skin against the rocks and mud below. It’s considered a globally significant Important Bird Area by Audubon and BirdLife International, because it hosts the highest diversity and abundance of birds of any lagoon system in the Alaskan Arctic.

Utukok River Uplands Special Area

The 7-million-acre Utukok (Inupiaq for “old”) Uplands Special Area sweeps down from the Brooks Range toward the coast, providing calving grounds for the Western Arctic Caribou Herd, one of the two largest herds in Alaska. Forty Alaska Native villages depend on the herd for subsistence. Grizzly bears, wolves, and a dense population of wolverines roam the remote, rocky peaks of the uplands.

Colville River Special Area

The 2.44-million-acre Colville River Special Area contains the largest river in Arctic Alaska and delineates the eastern boundary of the reserve. “It’s the highest-density raptor-nesting area in the Circumpolar Arctic,” says Melanie Smith of Audubon’s Migratory Bird Initiative. The cliffs along the river are home to Peregrine Falcons, Gyrfalcons, Rough-legged Hawks, and Golden Eagles. The Colville River Delta is also a globally important area for Brant; some 40,000 Brant stage every year on the delta’s mudflats after breeding.

Over the ensuing few decades, Alaska Fish and Game, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Audubon, the University of Alaska, and Indigenous communities of the North Slope laid the groundwork for the designation of five Special Areas. But Senner says the “maximum protection” required by Congress was never really spelled out.

“They were just lines on a map,” he says. “There was really very, very little that was different about management of a Special Area than management of the rest of the reserve. That started to change with the Obama plan in 2013, and the BLM started to take Special Areas more seriously.”

Early in his second term, President Obama’s Interior Department issued a Record of Decision that reinforced the NPR-A’s dual mandate—to provide certainty for a supply of oil, but also to protect critical ecological resources. Today those dual objectives are increasingly at odds. For the past century this reserve has been a safe birthplace for millions of birds. But now, even as nations set ambitious targets to slow climate change caused by burning fossil fuels, the oil industry is preparing to drill its leases within the very heart of NPR-A before they expire.

NARRATOR: In the remote coastal fringes of northern Alaska, a brief window is opening. Winter’s darkness is yielding to a sun that won’t set for the next 3 months. As days lengthen, birds return, and life is given another chance. Eiders, traveling more than a thousand miles from wintering areas in the Pacific, are impatiently pushing north to breed. They follow the open water, the cracks in the sea ice. At the peak of their migration, hundreds of thousands can pass this point in a single day. Males are adorned in the bright colors of courtship, females in colors that will hide their nests. Their success will be measured by the number of young they can produce before this seasonal window closes.

The Eiders won’t be alone–dozens of other species and millions of individual birds are coursing northward from distant parts of the globe, making their annual return to the lands where they were born. Coming to usher in a new generation in one of the most important arctic wetlands in the world.

[Text on screen] AMERICA’S ARCTIC. Teshekpuk Wetlands

[Text on screen] JUNE 1

After traveling great distances to Alaska’s northernmost wetlands, the first order of business for most birds is finding a meal. Where there’s water there’s food, and open water attracts a crowd. The Teshekpuk wetlands provide something for everyone. Birds can find food here regardless of how they feed or what they prefer to eat. Greater White-fronted Geese work the exposed tundra to get at the nutritious roots of grasses and sedges. Stilt Sandpipers and Long-billed Dowitchers probe for invertebrates and pick last season’s seeds released from the thawing ice. And Pacific Loons pursue fish along the open edges of tundra ponds. The abundant food that birds find in these wetlands fuels the breeding season. For birds that arrived alone, that means it’s time to find a mate.

[Text on screen] JUNE 10

Standing about 4 inches tall and weighing no more than six nickels, this male Semipalmated Sandpiper has flown from the northeast coast of South America to the very same territory he held last year. When you’re a small bird trying to stand out in a vast windswept landscape you need a strategy for attracting attention.

The male Semipalmated Sandpiper takes to the air. He’ll spend nearly 4 hours a day in flight, fluttering above the tundra, vocalizing a constant stream of gurgles and trills that advertise his presence. If this sandpiper is lucky, his mate from last year will find him and they’ll nest again.

The male Buff-breasted Sandpiper is also small but he has a completely different approach for attracting attention. Everything about his appearance resembles his surroundings except one… Nothing stands out on this landscape like a brilliant flash of white. His relentless wing waving advertises his presence to passing females. He’s flown all the way from Argentina to be here, to compete with other males that maintain territories immediately adjacent to his. If he’s flashier than the others, maybe he’ll get the first shot at finding a mate.

When wing waving doesn’t do the trick, he turns it up a notch. Maybe getting off the ground will get him noticed. His hard work appears to be paying off. A female has arrived on his territory. Turning his back to her he preens his feathers, enticing her to come closer. When she’s close enough, the real show begins. The sound and appearance of his courtship display are meant to impress. She carefully inspects every detail until she’s made her choice. Once they’ve mated the relationship ends, and she departs to nest and raise their chicks alone.

[Text on screen] JUNE 20

Shorebird nests are exquisite–4 eggs, perfectly arranged for incubation and heat retention. Camouflaged and tucked neatly into the vegetation, their appearance is what keeps them safe. From above the bird and nest are a perfect match for their surroundings. When still, shorebirds, like this Dunlin, virtually disappear.

If shorebirds are the masters of camouflage, Tundra Swans are the opposite. This couple used the same nest last year, but it needs some updating. The added height will provide a good vantage point to watch for predators that prowl the landscape.

Birds of the Arctic aren’t just faithful to their nests; many are faithful to each other. These Tundra Swans are lifelong mates returning each year from the marshes of Chesapeake Bay to the very piece of tundra they have occupied for years.

King Eider pairs will often establish a nest in the female’s place of birth. While’s she’s producing eggs her mate will remain close by, guarding her so she can feed and rest undisturbed. And Long-tailed jaegers spend 10 months at sea before reuniting each year on the tundra to nest and raise their chicks.

Each species manages the breeding season differently, but the goal is always the same. In the case of this Yellow-billed Loon pair, the goal is to keep their 2 eggs safe and warm for the next 4 weeks. It’s difficult to overstate the extent of wetlands on Alaska’s Arctic Coastal Plain. Lakes, ponds, rivers, and wet meadows form a mosaic of tundra habitats that are irresistible to birdlife.

[Map graphic showing Arctic Ocean and Brooks Range]

Located between the Brooks Range to the South and the Arctic Ocean to the North, the Arctic Coastal Plain stretches for hundreds of miles across Northern Alaska. Underlain with permafrost and sitting less than a hundred meters above sea-level, the region is more water than land. The expansive wetlands concentrated around Teshekpuk Lake are especially productive for birdlife, with some of the highest known densities of breeding shorebirds anywhere on earth.

Birds fan out across this landscape and nest here in astonishing numbers. The coastal plain provides vast tracts of undisturbed habitat and an abundance of food. Summer produces an explosion of insect life and plant growth and twenty-four hours of daylight provides the opportunity to feed around the clock. The abundant resources fuel a short but rapid reproductive season, drawing millions of birds from around the world year after year.

[Text on screen] JULY 06

Almost a month has passed, and patience is paying off at the lakeside nest of the Yellow-billed Loons. Being a good loon parent means providing a steady supply of fish that are just the right size for your finicky chick. Within days of hatching, loon chicks join their parents on the lake and begin a life spent almost entirely on or under the water.

All across the tundra, the landscape is becoming a nursery for hungry baby birds. Shorebird chicks are on their own when it comes to food. Within hours of hatching, they begin to explore the tundra around their nest in search of their first meal. They won’t stray too far at this point, and still rely on their parents for warmth and protection. Most have only 2 months before they’ll need to be strong enough to make their migration south.

If one thing’s for certain, it’s that chicks born on Alaska’s arctic coastal plain have a long way to go. Greater White-fronted Goose chicks will follow their parents to the coastal marshes of Texas and Louisiana. Brant will travel the Pacific Coast to Mexico. American Golden Plovers, Pectoral Sandpipers, and Buff-breasted Sandpipers will spend their winters in Argentina and Uruguay. Red Phalaropes and Long-tailed Jaegers winter far at sea off the coasts of Peru and Chile. Dunlin, Red-throated and Yellow-billed loons will return to the coasts of China, Japan, and Korea. And many other species will migrate to wintering areas across North America. But perhaps most remarkable are the Bar-tailed Godwits. Their chicks, just 2 months after hatching, will travel nearly the entire length of the Pacific Ocean on a nonstop 7,000-mile flight to New Zealand.

While most of the US is enjoying the last warm days of summer, the window for birdlife is rapidly closing in the arctic. Red Phalaropes are gathering on the arctic coast, preparing for the next 9 months at sea. The last remaining family groups of geese are waiting for just the right winds to usher them south. And young Arctic Terns are about to embark on a journey that, over their lifetime, can take them the equivalent distance of traveling to the moon – and back.

Yet, as they cross the globe, always on the wing in search of food, they’ll never fail to return each year to this place. The birds born here, like their parents before them, will be forever devoted to this land. No matter what corners of the globe they may occupy, or how far they may travel, it’s these vast wetlands, their birthplace, that they’ll always have in common. The place they’ll return to year after year, retracing the very steps of their own birth, taking advantage of a brief window to usher in a new generation of life in the pristine expanse of America’s Arctic.

[Text on screen] AMERICA’S ARCTIC. Teshekpuk Wetlands

[Credits][Text on screen] Produced by The Cornell Lab of Ornithology in association with Campion Foundation. Producer Gerrit Vyn; Editor Eric Liner; Written by Eric Liner, Gerrit Vyn; Executive Producer John Bowman; Narrator Betsy Winchester; Science Editor Irene Liu; Cinematography Gerrit Vyn, Neil Rettig, Florian Schulz, Eric Liner, Michael Mauro, Shane Moore, Matt Aeberhard, Tim Laman; Animations Jeff Romero; Color Darren Hartman; Sound Michael “Gonzo” Gandsey

[Credits][Text on screen] Additional Sound Recordings Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Field Audio Jamie Drysdale, Gerrit Vyn; Camera Assistants Jamie Drysdale, Nicole Frey, Evan Vacek, Tom Zimmer; Field Production Manager Emil Herrera-Schulz; Arctic Field Logistics Florian Schulz Productions; Unit Production Manager Chris Corrigan; Media Management Silvia Briga, Sara Carter Conley; Accounting Vanessa Powell, Karen Workman; General Migration Routes Provided By Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Bart Kempenaers, Rick Lanctot, Vijay Patil, Sara Saalfeld, Candace Stenzel, Lee Tibbetts, David Ward, Global Flyway Network, Max Planck Institute, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, USGS Alaska Science Center, USGS Bird Banding Laboratory

[Credits][Text on screen] Special Thanks: Samantha Beaman, Helen Cherullo, James Fulcher, Rick Lanctot, Joe Liebezeit, Erika Lundahl, Ru Mahoney, Rebecca McGuire, Debbie Nigro, Amy Peloza, Kayla Scheimreif, Barrow Whaling Captains Association, Bureau of Land Management, Community of Utqiagvik, North Slope Borough, UIC Science

[Text on screen] © 2024 Cornell University

End of Transcript

Teshekpuk Lake—The Most Special Area

The five Special Areas—totaling 13 million acres within the 23-million-acre NPR-A—were chosen because of their extraordinary ecological value for birds, caribou, marine mammals, subsistence for Indigenous communities, recreation, and wilderness.

Melanie Smith evaluated the NPR-A Special Areas as a spatial ecologist at Audubon Alaska starting in 2008 and helped to identify key bird and mammal habitat. Now Smith is the digital science and data products director for Audubon’s Migratory Bird Initiative. In terms of important bird habitat, Smith says that NPR-A checks all the boxes.

“There is a dose of mystery about why a bird would be compelled to fly many thousands of miles, sometimes from one tip of the continent to the other, one tip of the hemisphere to the other,” she says. But the nutrients and protection offered by the vast Arctic wetlands make those long journeys worth it, Smith says: “When they get to the other end of that journey, they need food, clean air, clean water, and that sense of safety that it’s a good place to build a nest and raise chicks.”

Birds migrate from South America, Asia, even as far as the coastal waters off Antarctica, to breed in the NPR-A in spring and summer—with its 24 hours of daylight; prodigious black clouds of mosquitoes, flies, and midges; and, most importantly, its polygon wetlands, sloughs, ponds, rivers, and deltas that shape the spongy Arctic tundra.

The Teshekpuk Lake Special Area—a 3.65-million-acre expanse of coastline, wetlands, barrier islands, and the Ikpikpuk River Delta—is perhaps the most special of the NPR-A’s Special Areas, according to Smith. “Teshekpuk” means “great enclosed water” in the Inupiaq language. Teshekpuk Lake is the largest lake in Alaska’s Arctic, and one of the most important places in the entire Circumpolar Arctic for waterbirds. The coastline and barrier islands also provide critical denning habitat for polar bears and calving grounds for the Teshekpuk Lake Caribou Herd, an estimated 40,000 animals that are a major source of subsistence for North Slope Indigenous communities.

“Ecological values just really stack up around Teshekpuk Lake,” says Smith. “For birds and for other species like caribou and polar bears, it’s really the crown jewel.”

Senner agrees: “You can’t walk 10 feet without flushing a nesting shorebird.”

A Globally Important Area for TUNDRA-Breeding BIRDs

The National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska is about the size of Indiana, but its tundra lakes and wetlands are of outsized importance as breeding habitat for birds that travel the world. The NPR-A supports more waterbirds than any other place in the Arctic, including more than 660,000 ducks, geese, loons, and grebes; more than 4.5 million shorebirds; and nearly 200,000 gulls, terns, and jaegers. Altogether, the reserve supports more than 5 million waterbirds, which is 10 times more than the estimated breeding population of waterbirds in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. After the summer breeding season, the concentrated density of birds in the NPR-A disperses across the globe. Bird migrations out of the NPR-A reach all seven continents on Earth, with large numbers funneling down the East Asian/Australasian Flyway and all four North American flyways.

Sources: Waterbird abundance figures from Bart et al. 2013. Bird migration routes based on data from Heiko Schmaljohann (wheatear), USGS Alaska Science Center (loon), Global Flyway Network (godwit), Autumn-Lynn Harrison (jaeger, tern), David Ward and Vijay Patil (Brant), Sarah Saalfeld and Bart Kempenaers (phalarope), Rick Lanctot and Lee Tibbitts (sandpiper), Craig Ely and Brandt Meixell (swan). Graphic by Megan Bishop.

Photos: Loon, godwit, and Teshekpuk Lake inset by Gerrit Vyn. From Macaulay Library: wheatear by Wojciech Janecki; jaeger and tern by Autumn-Lynn Harrison; Brant by Volker Hesse; phalarope by August Davidson-Onsgard; sandpiper by Luke Seitz; swan by Jack Belleghem.

The Teshekpuk Lake wetlands complex has the highest-density nesting habitat in Alaska’s Arctic for breeding shorebirds. Over half a million shorebirds—at a density of 126 shorebirds per square kilometer—probe the lake’s mud for worms and insects, and nest in its grassy shores and sedges. Teshekpuk Lake is an important breeding area for more than a dozen shorebird species.

All these shorebirds are joined by several species of geese, ducks, and loons, as well as Snowy Owls and Long-tailed Jaegers. Put it all together, and the level of bird breeding activity around the lake in spring is frenetic, raucous, and just plain loud.

“You’ve got all these birds in motion, feeding, courting, squabbling over territories, and chasing predators. Geese are honking, loons are wailing, Long-tailed Ducks are yodeling, and shorebirds have exuberant songs you only hear on the tundra,” Senner says, recalling his days as a shorebird biologist camped beside the lake. “There are birds everywhere calling; it’s really extraordinary.”

One bird in particular, says Smith, is most emblematic of the importance of the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area.

“I have a lot of access to data,” she says, squinting at the numbers and graphs on her computer screen, an inventory of bird abundance around the lake. “If I zoom in to see which species are in high abundance, I can come up with 20 right away where this is just the best of the best possible habitat. And then if I want to see which of those 20 are highly vulnerable to climate change … and which are sensitive to oil and gas development, the intersection of all those things is the Yellow-billed Loon.”

With their large and distinct yellow bills, these loons are highly territorial as they nest and feed in the myriad freshwater lakes and ponds. Smith says 75% of the U.S. breeding population of Yellow-billed Loons nests within the NPR-A, primarily in the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area.

Smith and Senner both stress that it’s not just the numbers of birds at Teshekpuk Lake and throughout the NPR-A that make this land important, but the connectivity of so many different species that fly thousands of miles from all over the globe to spend a brief, seasonal window in this one place. That connectivity makes the best case for protecting the NPR-A’s Special Areas, they say.

“When we are talking to someone who is a duck hunter,” says Smith, “they care about conservation of waterfowl. If we talk about a Northern Pintail, well there are Northern Pintails all over the place, but we can show them that it’s actually their Northern Pintails, that come here, that might be affected by climate change and oil and gas development.”

A New Project to Drill, And a New Rule to Protect

Hundreds of oil and gas test wells have been drilled within NPR-A over the years, and industry has acquired the development rights to 2.5 million acres within it. There are currently three projects producing oil in the reserve’s northeast corner. The Trump administration tried to expand oil and gas leasing and reduce protections for the Special Areas, but that effort was overturned by the Biden administration.

Last September, President Biden proposed a new conservation rule that strengthened Special Areas protections. Reaction in the conservation community was mixed. The rule would prohibit new leasing in 10.6 million acres of the reserve and require strict guidelines for another 2.4 million acres, protecting about half of the entire reserve. But the Biden administration did not change course on its approval of the Willow project, oil and gas leases to the east of Teshekpuk Lake that have been held by ConocoPhillips for more than 20 years.

While Biden reduced the size of development from five drilling sites to three, and ConocoPhillips agreed to give back leases to 68,000 acres within NPR-A, the White House gave the green light for extraction of what ConocoPhillips predicts will be 180,000 barrels of oil a day at its peak. The move avoided a costly legal battle with the oil company, which many predicted the administration would lose. But opponents say the project is a threat to the ecological values of NPR-A and would create a “carbon bomb” of emissions, the equivalent of adding 2 million cars to the nation’s roads every year of the project’s life.

Marilyn Heiman, former U.S. Arctic program director for the Pew Charitable Trust, is skeptical of any new development in the area: “Industry made promises that they would reduce the damaging footprint of drill pads, pipelines, and roads and air and water pollution in America’s Arctic, but those promises have not been kept.”

The state of Alaska, its congressional delegation, and most North Slope communities have rallied in support of the Willow project. The North Slope Borough’s regional government relies on oil revenue for 95% of its budget.

Schoen, the retired wildlife biologist, says he gets the economic argument.

More on Teshekpuk Lake and the Willow Project

“I’m a pragmatist. I’m not recommending that we have no oil and gas development in the Arctic,” he says, “but I certainly don’t think it’s responsible to continue this incremental piecemeal expansion of development without a comprehensive strategy.”

The proposed new rule by the Biden administration—which the Department of the Interior hopes to finalize this year—does recognize how dramatically the Arctic is changing due to a warming climate. For the first time, it would establish a process for balancing development with the protection of Special Areas, and would require the BLM to consider designating new, or amending existing, Special Areas every five years.

Senner says his wish list of amendments would link places like the Kasegaluk Lagoon Special Area and the Utukok Uplands Special Area, add acreage to the west of the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, and provide more protection for the sand dunes within the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area. The dunes are important nesting habitat for Yellow-billed Loons and provide places for caribou to escape biting insects. Senner says the dunes are currently off limits to oil and gas leasing, but could be mined by industry for sand and gravel roads.

“The ultimate objective is permanent protection for some of these extraordinary areas,” he says, “and by permanent, I mean legislatively established areas as opposed to administratively established, because the truth of it is that the Biden administration can do everything it wants, and it could still be undone by the next administration.”

That’s a constant worry, says Melanie Smith, who points out that only 2% of Alaska’s Arctic coastal plain is under permanent protection.

“It can be hard for people to see the importance of protecting something called ‘a petroleum reserve,’” says Smith. “It’s an unfortunate situation that the oil values and the bird values and the caribou values and the polar bear values all come together in one place. But we need to be protecting more of Alaska’s Arctic. Two percent isn’t enough.”

Schoen says he is proud of the work that’s been done by Audubon and others over the last 50 years, but he says more is needed. He is an advocate for a comprehensive, science-based conservation strategy for NPR-A, and the entire Arctic coastal plain, “so that we can provide what shorebirds and Yellow-billed Loons and caribou and polar bears need.”

“We still have the opportunity in Alaska to protect intact ecosystems with all their functional parts, what I saw from that airplane as a young biologist,” Schoen says. “But it’s going to take some compromise and some good information. We have the information, and we have the tools. But do we have the will?”

This spring as millions of birds all over the world are embarking on long migratory journeys back to their birthplace in the NPR-A, ConocoPhillips is wrapping up its winter construction season, mining gravel to build a network of roads that will lead to as many as 199 wells across the Willow project. Oil production is expected to begin in 2029.

About the Author

Elizabeth Arnold is a journalism professor at the University of Alaska and former longtime political correspondent for National Public Radio. She has received numerous journalism awards, including a duPont Columbia Silver Baton and the Dirksen Award for Distinguished Reporting of Congress. Over the last decade, she has reported on the ecological and human impacts of global warming from some of the most remote areas of the Arctic.