When you hear about accessibility, what do you think of? When you play a Souls-like game, what do you think of? If both of those answers are about difficulty, you’re partially correct. But not in the way you think.

In 2019, a Forbes opinion article arguing FromSoftware’s Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice needed an “easy mode” sparked a toxic debate on social media. Like most online debates, it eventually died down, then flared up again whenever another Souls-like game came out. So the reductive misconception of accessibility as “easy mode” continued to spread.

Ahead of the release of Elden Ring, series creator Hidetaka Miyazaki told PlayStation Blog his games are about more than simply being difficult. “We want players to use their cunning, study the game, memorize what’s happening, and learn from their mistakes,” he explained. In other words, his games aim to cultivate an enjoyable sense of challenge and the exhilarating feeling of success through perseverance. Broadly speaking, accessible design aims to avoid excessive or unnecessary difficulty, but there’s a lot more nuance to it, too. So let’s unpack what accessibility truly is, why difficulty is different for everyone, and what games you should play that are both accessible and keep challenge intact.

Accessibility 101

In video games, accessibility focuses on avoiding unnecessary mismatches between a player’s capability and a barrier. It goes beyond simply helping disabled players play video games. Accessibility can help anyone, regardless of whether they are disabled or not.

Ian Hamilton, an accessibility specialist with 15+ years of experience, explains that accessibility is two-fold: design and options. As it’s not always possible to avoid barriers with design alone, “the wide spectrum of human variation means that sometimes we have to fall back on options too, where different players have conflicting needs and preferences.” In other words, the abundance (or absence) of accessibility options in a game only tells half the story.

The design aspect is more complicated, and often specific to an individual game or scenario. Hamilton brings up the example of using color in games. A game like Call of Duty may divide players into teams distinguished by color, like red vs. blue. Good accessibility practice accounts for players who may have trouble seeing those colors, so developers also create logos or symbols to correspond with each team.

Usually, there is no “one size fits all” approach. Human variance means that while a feature can be playable by some, it won’t be for all, even if it was designed with disabled players in mind. And that’s the key term, as Ian puts it: “spectrum of human variation.” Every human is unique and has a wide range of abilities and capabilities. Abilities can be improved and practiced. Capabilities are hard ceilings that can be impacted by impairments, and impairments are rarely ever an on/off switch. Often disability is seen in either/or terms: you’re completely blind or not, you are fully deaf or not. Disability, like all human experiences, is a spectrum. No two experiences are exactly the same.

Difficulty is in the hands of the beholder

In online debates about difficulty vs. accessibility, you may have heard the following phrases: “This game was made to be difficult,” or “I’m all for accessibility, but accessibility and difficulty are two different things.” Often, these arguments are made in defense of a studio or director’s presumed “artistic vision.” But is that accurate? In a Game Accessibility Conference talk in 2021, Hamilton did a six-minute talk about this exact topic. It is a great resource to bookmark and watch fully to grasp this conversation.

Essentially, Hamilton contends that difficulty—at least as we’ve come to think of it—does not actually exist. Sure, we have decades of games offering Easy, Normal, and Hard options. But Hamilton contends that difficulty is relative to the person, due to the human variance I mentioned earlier. Hamilton explains that difficulty “is something that springs into existence when people play the game. It’s is a product of personal capabilities versus the barriers that a game presents.”

When we think about it in these terms, disability doesn’t equal an impairment. It’s a mismatched interaction with a barrier, resulting in difficulty in completing a task. To help explain it in gaming terms, say an enemy is about to attack you from off-screen. You can’t see it, but you can hear it about to attack, which can be an intentional barrier that the player is supposed to overcome. So if the designer wanted that encounter to be at a difficulty level of 5, consider the scenario of a deaf or hard-of-hearing player who cannot hear that sound. Now, that difficulty is closer to a 10. The interaction between the player and the game is mismatched, presenting a barrier. Accessibility means avoiding that mismatch by adding a visual cue on the screen, like an arrow or a flash of color, so the attack isn’t presented by sound alone. Now the attack is back to a difficulty of 5—the way the designer intended.

So, does making games more accessible remove the challenge? ”The most important thing that is missed in these kinds of discussions is that “Easy” and “Easier” are very different things,” Hamilton explains. “Making a game easier is not the same thing as making it easy. You can make a game hard by making it easier, because hard is easier than impossible. Everything in accessibility is fundamentally about making things easier, avoiding or removing unnecessary excess difficulty that inaccessibility causes. But that is not the same thing as making it easy.”

So what about challenge?

If difficulty is unique to each individual, and making a game accessible eliminates barriers for disabled players, what about a game’s challenge? Can you make a game challenging but also make it accessible? Turns out, you can. There are some fantastic video games that keep challenge intact while being accessible for disabled players. Here are three exceptional examples that came out in 2023.

Forza Motorsport

An in-the-weeds racing sim may not seem accessible on the surface, but the team at Forza developer Turn 10 Studios has introduced some incredible innovations to enable more people to enjoy their game. They made the latest Forza accessible to blind players with a new feature called “Blind Drive Assist,” which gives audio cues to let them know where they are on the track at all times. True to the series’s simulation roots, Forza Motorsport just provides info about the track—it’s still up to the player to decide how they want to race.

Street Fighter 6

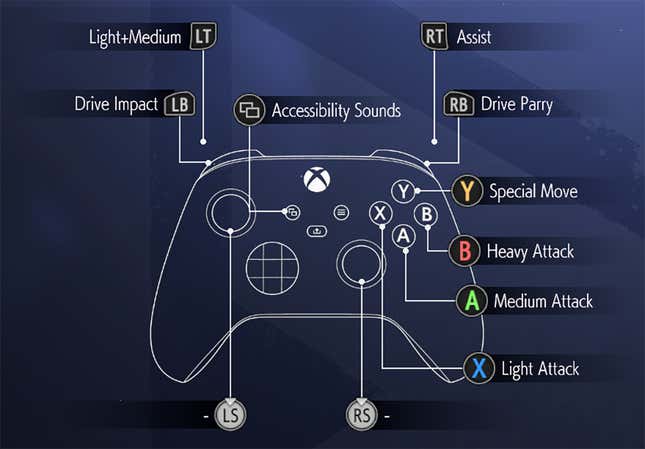

This game is huge for disabled fighting game fans. It includes three distinct input modes—Dynamic, Modern, and Classic—and the option to use simplified control schemes makes it super welcoming to many disabled players. It gives folks who don’t have much experience with this intimidating genre the opportunity to learn and progress. Then they can train with a favorite fighter and even get into competitive play, because Modern controls are allowed in official Street Fighter tournaments.

Star Wars Jedi Survivor

When Fallen Order came out, reviews widely compared the game’s parrying and dodging system to Dark Souls. But EA’s Star Wars games also include multiple difficulty modes that make the combat system a little more generous for those who need it. With Jedi Survivor, the Respawn team added a ton more accessibility features, such as an option to slow down the game if you need extra time for parries and dodges. They also added a new difficulty mode, Jedi Padawan, based on player feedback.

There are a lot of misconceptions about accessibility and disabled players. And if you have some of those misconceptions, that’s okay. If you are not exposed to how a disabled player may need accessibility, or you’re not around disabled people in your day-to-day life, you may not think about the needs of disabled players at all. But I hope this leaves you with a better understanding of accessibility and how we, as advocates, consultants, and developers, are not trying to take your game away from you. Accessibility simply helps us choose what we want to play—rather than having that choice made for us.