When football great Abner Haynes died last Thursday, at age 86 (his cause of death has not been reported), the news prompted loving reflections on the Texas Sports Hall of Fame inductee’s storied athletic career. Haynes was the most valuable player of the American Football League as a rookie in 1960, when he suited up for his hometown Dallas Texans. He helped Dallas win the 1962 AFL championship, before the franchise up and left to become the Kansas City Chiefs.

Before beginning his eight-season pro career, Haynes helped break the football color barrier for Texas’s four-year colleges in 1956, when he joined the team at North Texas State College (now the University of North Texas), in Denton. That was eight years before Warren McVea signed with the University of Houston, an academic independent at the time, and nine years before SMU made Jerry LeVias the first Black scholarship football player in the Southwest Conference.

Haynes walked on at North Texas after excelling in football and track at Lincoln High, one of the all-Black schools in Dallas. But he wasn’t alone in breaking that barrier for Black athletes in the state. He had one of his high school classmates, Leon King, with him.

North Texas had only recently admitted its first Black students when Haynes and King set foot on campus. The school’s first Black student was 41-year-old Alfred Tennyson Miller, who enrolled in doctoral classes in June 1954, only weeks after the historic Brown v. Board of Education ruling by the Supreme Court. The first Black undergrad enrolled in February 1956. The first Black freshman class arrived that fall, with Haynes and King among them.

They both made the football team, and King experienced the same trepidations and fears as Haynes. He suffered the same indignities from opposing fans—and sometimes from teammates. King didn’t put up the same gridiron numbers as Haynes, but he too deserves inclusion in the Texas Sports Hall of Fame for what he endured and for the role he played in state history.

When Haynes and King arrived at North Texas’s Fouts Field on September 1, 1956, for the first day of preseason football drills, they stepped out of a cab and walked toward their new white teammates. Three of them—Garland Warren and brothers Charlie and Vernon Cole—likewise walked toward King and Haynes. Once the parties were close enough to introduce themselves, the white players welcomed the Black walk-ons. Not all the other North Texas players were so kind. Mac Reynolds, a junior from East Texas, a hotbed of racial tension at the time, confronted Haynes after that first practice. The lineman said he had no intention of showering with Black teammates and asked why Haynes and King didn’t attend one of their schools.

A fellow freshman, Raymond Clement, mentioned the two Black players to his parents while describing his struggle to adapt to college football and his thoughts of quitting the team. Clement suspected that telling his folks that he was playing on an integrated roster might convince them to give him their blessing to quit. Instead, his mother said in so many words: If you want to play football, you play football. If you want to quit because it’s too tough for you, you quit. But don’t blame it on two Black players. Clement stayed.

King and Haynes lived off campus and weren’t allowed to eat in the athletic dining hall because, they were told, it was reserved for scholarship athletes. Vernon Cole, also a freshman, was among the white teammates who often brought food and drinks to them.

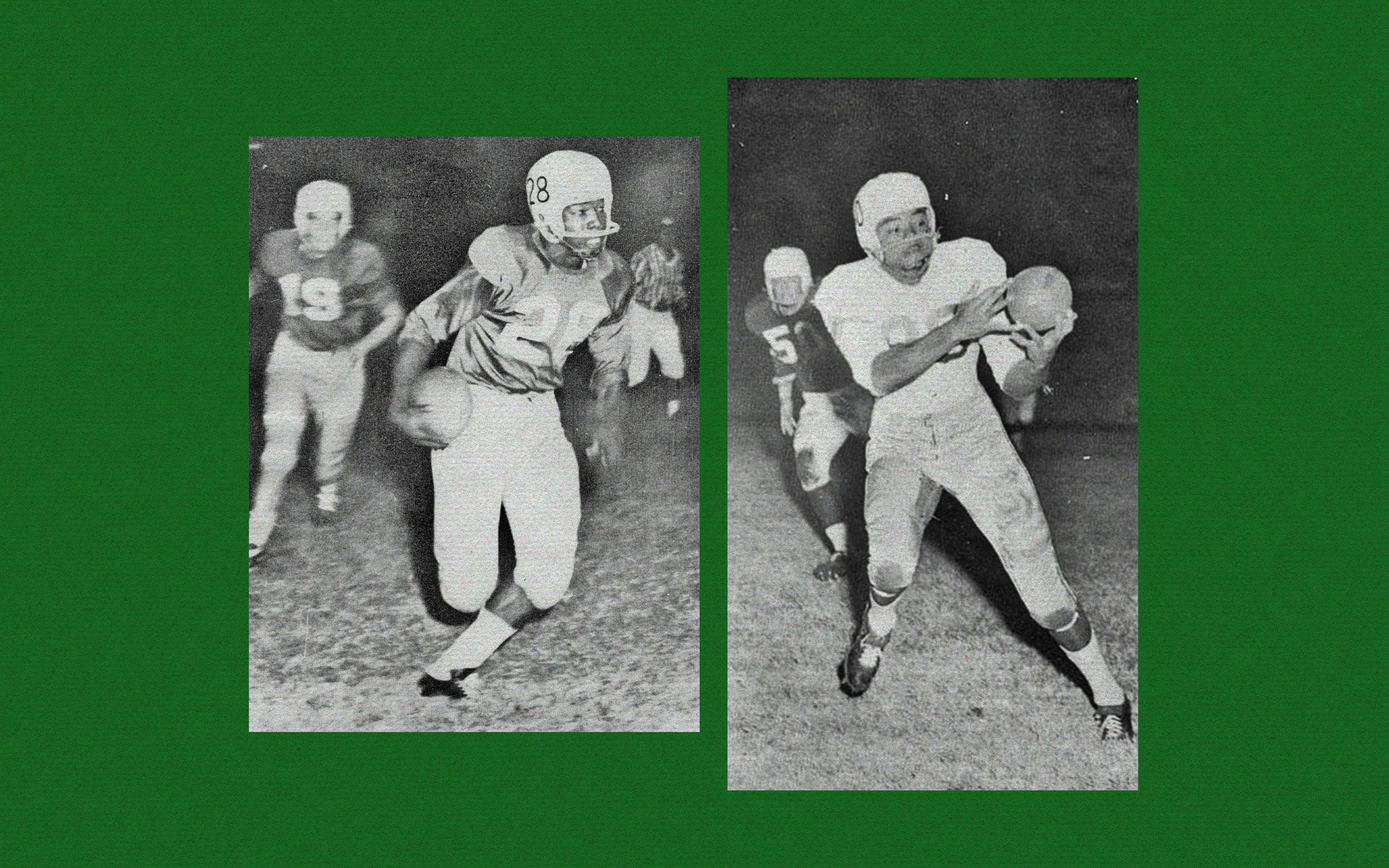

In those days, freshmen weren’t eligible to play NCAA varsity football, so Haynes was a starting running back and King a starting end on the Eaglets freshman team. Their coach, Ken Bahnsen, had played for North Texas only a few years earlier. They played their first road game in Corsicana, against Navarro Junior College (now Navarro College), which had an all-white roster. When the North Texas traveling party stopped in town for a pregame meal, a restaurant employee said the Black players would have to eat in the kitchen instead of in the dining room with the rest of the team. Bahnsen decided it would be a carryout meal.

When North Texas arrived at Navarro’s home stadium, an attendant asked Bahnsen if he planned to put the Black players into the game. When told yes, the attendant said, “Well, they might die.” During warm-ups, Navarro fans chanted a racial slur at King and Haynes. North Texas won, 39–21, with King and Haynes in pivotal roles. After the final whistle, Bahnsen told his players to head straight to the bus in their uniforms, leaving their helmets on for protection from potential attacks.

After the Eagles freshmen won their season finale at home, a group of North Texas cheerleaders, who were white, greeted the team—including King and Haynes—with hugs. King later admitted the interracial embraces “frightened me a little.”

Haynes and King moved up to the varsity team as sophomores in 1957. It was North Texas’s first season as a full-fledged member of the Missouri Valley Conference, and more Black players joined the team. Haynes led the league in rushing, and King was third in receiving yards. Among their biggest boosters was Mac Reynolds.

King’s mother, Jesse Mae, never wanted her son to play football, especially at the collegiate level. He convinced her to watch a game that fall, telling her, “You shouldn’t have any problem trying to pick out which one I am.” After the 1957 season, King suffered a knee injury that kept him off the field throughout most of his remaining time at North Texas. By then, he was married and helping his wife raise their first child. After the couple had a second child in December 1958, King left school to return to Dallas and focus on supporting the family.

Haynes and North Texas reached football heights in 1959 that the Denton school had never before scraped. The then-Eagles won their first eight games, earned a number sixteen ranking the Associated Press poll, and finished 9–2 with an appearance in the Sun Bowl. Haynes, a senior, was named an All-American by Time magazine. That 1959 North Texas roster featured several Black players.

Contrast that with what was happening—or not happening—elsewhere in the state. Three days after the ’59 North Texas squad ran its record to 8–0, the University of Texas’s dean of students drafted a memo to the school president detailing how the coaches of the most prominent Longhorns teams—football, basketball, baseball, and track—wouldn’t favor the athletic department bringing in Black athletes. (UT’s track team was integrated in 1963, by James Means, the first Black athlete in the Southwest Conference; the football program was integrated in 1969, by Julius Whittier.)

Jesse Mae King died in January 1961. Soon after, Leon King returned to college at North Texas to honor his mother’s wish that he graduate. He earned a bachelor’s degree in August 1962 and almost immediately began working as a teacher in the Dallas school district. That fall, he taught science and coached junior high sports back at Lincoln. One of the most notable athletes to come through the school then was Duane Thomas, the running back who’d go on to lead the Dallas Cowboys to victory in Super Bowl VI—the franchise’s first championship.

King remained in education, serving as a principal at multiple Dallas ISD schools over the course of a career that spanned four decades. He retired in 2000—though he continued to fill in part-time when needed. In the spring of 2004, North Texas honored a handful of individuals from that groundbreaking 1956 freshman team. King and Haynes were there. So were Ken Bahnsen and Raymond Clement.

King and Haynes appeared together on campus for the last time in November 2022, when North Texas dedicated its new Unity Plaza to the two football trailblazers. The news of Haynes’s recent death is a bittersweet reminder of the two men’s impact on Texas college sports—and an urgent reminder that King, who is now 85, deserves to join his former Lincoln High and North Texas teammate in the Texas Sports Hall of Fame.

Jeff Miller is the author of The Game Changers: Abner Haynes, Leon King, and the Fall of Major College Football’s Color Barrier in Texas.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.