Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here

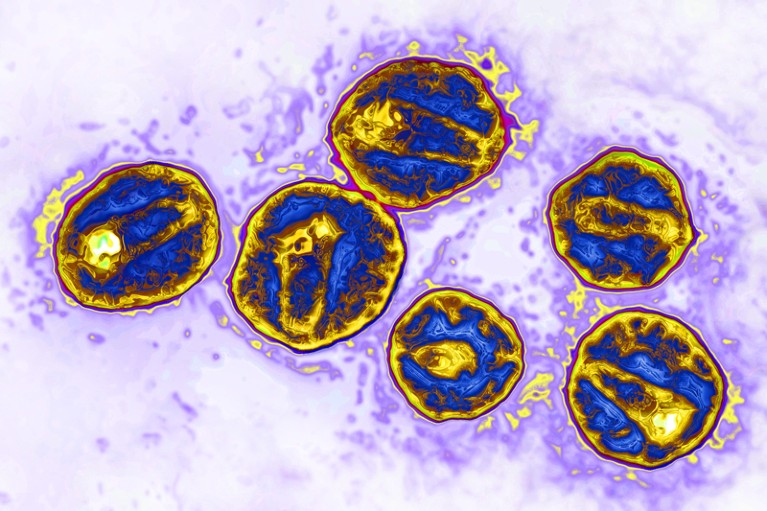

HIV particles (pictured) use a receptor called CCR5 to infect human cells. A particular mutation in this receptor makes cells resistant to the virus.Credit: James Cavallini/Science Source/SPL

A 53-year-old man in Germany has become at least the third person with HIV to be declared cleared of the virus after undergoing a procedure that replaced his bone marrow cells with HIV-resistant stem cells from a donor. The man, who is being referred to as the ‘Düsseldorf patient’, received the treatment after being diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia. Stem-cell transplants are not suitable for people who don’t need them to treat blood cancer because they are risky and difficult: the man called his treatment a “very rocky road”.

Reference: Nature Medicine paper

Researchers have built on their Ig-Nobel-prizewinning research into why wombats are (probably) the only animal in the world that produces cubical faeces. Their surprisingly long and intermittently stretchy intestines compress their stool into cubes. Now the team has pinpointed another factor, which seems to apply to all animals that produce faeces in pellet form: how the poo dries in the animals’ guts. Researchers passed corn-starch ‘poo’ through plastic trough ‘intestines’ under drying heat lamps. Greater drying resulted in more closely spaced cracks — wombat poo, which contains 65% water, cracked into little cubes. Human poo, made up of 75% water, comes out in longer tubes, and cow pat, containing up to 90% water, just slops right out.

Reference: Soft Matter paper

Almost 60% of around 500 people who responded to a Nature survey use artificial-intelligence tools for “creative fun not related to research”. Brainstorming was the most common science-related use, cited by almost 30% of respondents. Many people highlighted how chatbots could speed up routine tasks, such as crunching numbers, debugging code or streamlining writing. At the same time, respondents were worried about the pitfalls, such as factual inaccuracies or the possibility that these programs could help ‘paper mills’ to commit research fraud on a large scale.

Features & opinion

As of 2022, more than 90% of the world’s DNA-sequencing data were generated on Illumina machines. Now, there’s a dizzying array of new sequencers, and labs need to carefully weigh their options. Does the project require a US$1-million behemoth that can churn out up to 6 trillion bases of sequence every 2 days, or could a benchtop system do the job? How do the publicly announced per-genome prices stack up against hidden costs for labour and maintenance? This guide will help scientists to navigate the intimidating and confusing range of emerging sequencing platforms.

Earth-system scientist Will Steffen, who has died aged 75, “epitomized the ethos of a social contract between scientist and society in his pursuit and sharing of knowledge relevant to the grand challenge of climate change”, write his colleagues Lesley Hughes and Martin Rice. Among his achievements was a seminal paper on nine ‘planetary boundaries’ — the limits of what Earth can support before human activities make it uninhabitable. Steffen was also a keen mountaineer. “When you come off a big climb, you really appreciate the beauty of what’s around you,” he said. “That’s the buzz you get in science when you solve a big problem and suddenly see how it all fits together.”

Reference: Nature paper (from 2009)

“I just feel they’re out of touch with women’s health,” says reproductive endocrinologist Richard Legro about the reviewers who keep rejecting funding applications for his work on dysmenorrhea. The condition — painful periods with or without an underlying medical issue, such as endometriosis — affects nearly one in five people who menstruate. Many don’t get relief from existing treatments. Yet some studies like Legro’s, which was trialling whether sildenafil citrate (sold as the erectile-dysfunction drug Viagra) could flush out painful stimulants, have been shelved. Clinical trials that do get funded often struggle to recruit participants who are willing to come into the lab when they are menstruating and in pain. Researchers are getting creative about how to carry on their work, for example by sneaking a small study into a large, multi-arm trial.

Where I work

Jiro Ueda is an art conservator at the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art in Washington DC.Credit: Stephen Voss/Smithsonian

In this image, art conservator Jiro Ueda carefully deconstructs centuries of repairs to a thirteenth-century Buddhist painting, before putting it back together with mulberry paper and traditional starch glue. “Japanese art conservation is not just about the finished product, it is also about preserving the cultural heritage,” he says. The field’s philosophy has changed dramatically over the last three decades: previously, if a work was damaged, it would be completely remounted. “Now we do as little as possible so that we can preserve the whole object.”

(Nature | 3 min read) (Stephen Voss/Smithsonian)