On a steamy June evening, Curtis Eckerman embarks on a mothing expedition in the Bauerle Ranch greenbelt, in far South Austin. Towing a wagon full of supplies, he follows a narrow trail that leads between mesquite trees and into a secluded oak grove suffused with golden late-afternoon light. Eckerman, the chair of the biology department at Austin Community College, parks the wagon and begins to wrap a tree trunk in white cloth. Next he suspends a battery-powered ultraviolet light from a low branch. He’s optimistic we’ll see lots of different moths tonight; it’s been a warm, humid day, conducive to plant growth and, by extension, activity by plant-eating creatures. The oak grove is full of frostweed, persimmon trees, and various grasses, each vital to different moth species. That’s another good sign: a wide variety of plants will draw a variety of moths.

When he finishes his preparations, it’s about eight o’clock. Moths emerge to eat, mate, and lay eggs once it’s completely dark—and fellow moth-ers will arrive any moment now. Eckerman mops his brow and takes a swig from his water bottle. “Now we just wait.”

Eckerman is a herpetologist by trade; he says the best job he ever had was catching endangered water snakes in West Texas as an undergraduate research assistant. But he’s always collected insects, and a little over a decade ago, he began photographing them. When he realized he struggled to identify the moths in his pictures simply because there were so many varieties, he dedicated a summer to studying them. These days, he sets a light by his garage door and photographs whatever moths show up, as many as seventy species and thousands of individuals in a single night. He’s now counted 550 species at his own home.

Eckerman is an ecologist with an interest in biodiversity, as well as in species’ natural histories, behaviors, life cycles, and places in the food chain. Moths are so diverse, he says, that it’s not uncommon to find one that hasn’t been named or described in the scientific literature. No entomologist studies “moths”; out of necessity, they specialize. Travis County has about 1,400 recorded species, the state of Texas more than 4,000. And those are just the ones we know about. Insects are the most diverse group of animals on the planet, and there are likely more undiscovered insect species than known ones—as many as 10 to 20 million species worldwide still left to discover, Rice University biologist Scott Egan told Texas Monthly earlier this year.

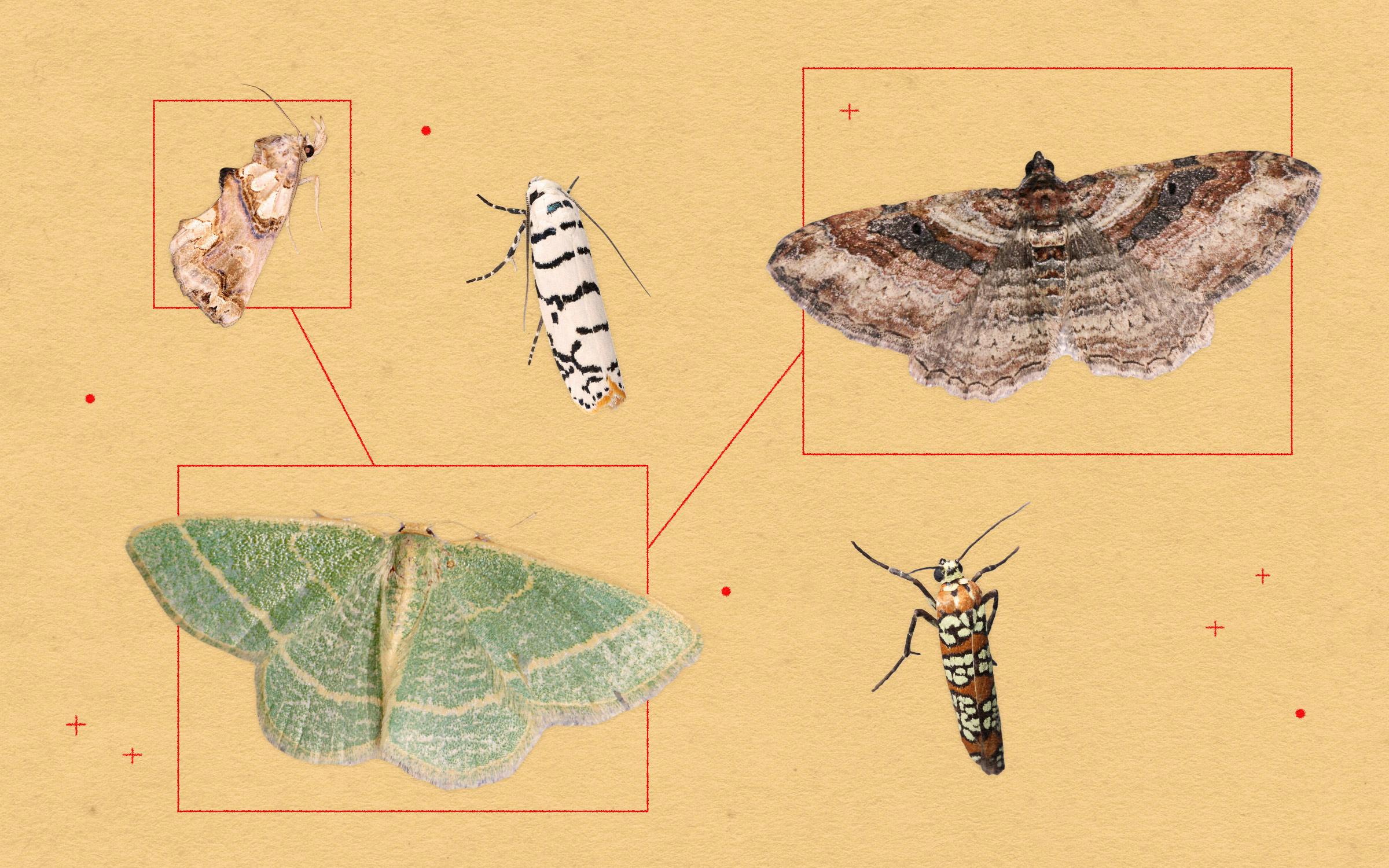

The most common type of moths in the U.S. are noctuids, the smaller, grayish-brown moths that congregate around porch lights—“Your stereotypical moth,” Eckerman says. Showier hawk moths are active during the day and often confused with hummingbirds. Silk moths, such as the luna moth, enormous and apple green, don’t have functional mouth parts; their one-to-two-week adult lives are powered by whatever fat they’ve stored as caterpillars. Micromoths—a broad descriptor that can include noctuids and moths in other families—have wingspans under twenty millimeters long, but worth viewing through a magnifying glass or camera to admire their vivid colors and patterns. They’re one of Eckerman’s favorite groups to photograph because of the “hidden-gem effect,” he says. “It’s the idea that you get to see something that somebody normally doesn’t see. . . . You feel like you’re exploring a world that others are not exploring, even though it’s around them all the time.”

Much of Eckerman’s moth self-education comes from the participatory science app iNaturalist. Users take pictures of plants, insects, and other animals they spot in their local areas and upload them with comments (“Anyone know what kind of owl this is?”). Fellow iNaturalists compare notes and help one another identify mystery species. The app also suggests possible identifications with an impressive degree of accuracy. Users can note the location where they saw a given plant or animal, creating a dataset that has helped researchers understand the ranges of particular species. Virtual communities form quickly and move into real life as users go mothing, birding, or herping together.

Eckerman posted his first moth images to iNaturalist ten years ago, and other users coached him on how to take better photos to make identification easier. He started teaching the students in his Structure and Function of Organisms course at ACC to use iNaturalist to log their own observations. Eckerman has tracked his former students’ engagement with the app via their usernames and found that three years after taking his class, 30 percent are still active.

Too many Texans are disengaged from the natural wonders around them, he argues, but iNaturalist can help them tune in. “The average student today could tell you all sorts of things about the plains of the Serengeti and interactions between zebra and lions, because National Geographic and Discovery and Disney brought it to us in high definition,” Eckerman says. “But they know far less about what’s in their own backyard than the previous generation, because they’re just not interacting with it.” Over the years, he’s stopped talking about faraway exotic animals in his courses; he instead makes lessons relevant by focusing local fauna students have actually seen: coyotes, gray foxes, grackles, moths.

To help his students apply their iNaturalist skills in the field, he organizes mothing expeditions to Pease Park, in Central Austin, and Roy G. Guerrero park, in East Austin. At the latter site, the classes have logged about 350 moth species, including an enormous black witch, longer than a chalkboard eraser and sometimes confused for a bat—it’s the largest noctuid in the continental U.S. Roy G. Guerrero is a much larger park than Pease and more buffered from human activity that would interfere with moths. Still, the Pease Park surveys have turned up more than two hundred species—proving, Eckerman says, that urban parks are important not just as sites of human recreation but also for supporting species diversity. In the spring, Eckerman invited the public to go mothing at the park, part of his ongoing effort to educate the general population about biodiversity and conservation. For impromptu events like the June expedition on the greenbelt, he maintains a “moth-lovers email list” and lets word spread on iNaturalist.

An hour after sunset, the afternoon buzz of cicadas has given way to the rhythmic rattle of katydids. A half dozen moth lovers gather in the oak grove and peer at the moths flittering against Eckerman’s sheet, including the indomitable melipotis, a large brown triangle with a cream-colored V across its wings, and the smaller filbertworm moth, its wings a mottled red with bands of gold.

Reid Hardin, a biology student at Texas State University, studies the moths before disappearing into the shadows to look for scorpions. Hardin’s into moths—he sometimes sets up a light in his own backyard—but he also scouts out rare plants and various arachnids. iNaturalist has connected him with locals who share his curiosity. Tonight, he and Caleb Helsel, a Westlake High School student who’s into birds, insects, and arachnids, are comparing notes on the pseudoscorpions they’ve turned up at Austin greenbelts. “It’s just always cool to see who else is interested in niche, nerdy stuff,” Hardin says.

Moths aren’t just pretty to look at; they’re also important pollinators and a major source of food for birds and bats. But moths, like insects overall, are declining in both raw numbers and species diversity. Eckerman says recent studies have shown at least a 30 percent decline in insect abundance around the world over the past few decades. The likely culprits are pesticides and the loss of habitat to urban development. A threat to insects such as moths is a threat to the plants they pollinate and all the creatures above them in the food chain.

Beyond eschewing pesticides, Texans can create more moth-friendly environments by using a variety of native plants in their yards to offer food. Reducing light pollution helps too; moths are disoriented by artificial light, which can impair reproduction. If moths lay their eggs under the light instead of on a plant that is their food source, the resulting larvae won’t have anything to eat. Turning off lights at night (Eckerman always disassembles his setup at the end of the evening) helps moths find their way to the right plant.

By 10 p.m., Eckerman’s sheet is littered with diminutive flying insects: micromoths, small beetles, caddis flies, and plant hoppers. He leans in to photograph a tiny moth, using a camera with a macro lens that lets him take clear images at a short distance. To the naked eye, the moth—smaller than a grain of rice—is plain white. But when Eckerman enlarges the image on the viewfinder, he reveals a pattern of buckwheat-colored flecks on cream-hued wings. Eckerman can’t remember its name—he just knows it’s in the Gracillariidae family—but iNaturalist will fill in the details.

Overall, he says, it’s been a good night for the really small moths, which makes him happy. “Despite there not being all that glamorous moths, this is actually my favorite kind of sheet, with all the tiny things,” he says. “I love seeing the little jewels that you can’t normally see.”