For four years in the thirties, the U.S. government invested in theater to an extent that seems impossible, even shocking, today. The Federal Theatre Project, one of a slew of New Deal programs designed to alleviate poverty during the Great Depression, created about 12,000 jobs and launched the careers of such greats as Arthur Miller, Orson Welles, and Paul Green (author of the Texas outdoor musical, performed to this day in Palo Duro Canyon). Some 30 million Americans watched the project’s free or very affordable plays—more than a thousand productions across 29 states. The majority of those in attendance had never been to the theater before, including immigrants who enjoyed shows staged in their native languages, such as Spanish and Yiddish. In Texas, Federal Theatre productions were mounted by dramatic companies, one-act play groups, a marionette unit, a ballet company, and a tent show theater. Many of the plays were politically and socially progressive, such as a touring production of Macbeth with an all-Black cast, who performed in the five-thousand-seat amphitheater at Dallas’ Fair Park. Those in attendance formed the city’s only integrated theatrical audience at the time.

This national experiment in the arts cost approximately $46 million (roughly $1 billion in today’s dollars) which sounds like a lot, until you consider that it was less than 0.5 percent of the Works Progress Administration’s budget. Other New Deal job-creation programs, such as the Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Youth Administration, were far larger and costlier. Some of the Federal Theatre’s shows even made a profit, which was delivered directly to the Treasury Department. As the Federal Theatre Project’s director Hallie Flanagan pointed out, the program’s cost was roughly equivalent to that of building a single battleship. But the effort was still too big and too bold for its critics, who led a successful campaign to defund and shut it down in 1939. The chief architect of this effort was a Texan: U.S. Representative Martin Dies, who was born in the West Texas town of Colorado City and grew up in Greenville and Beaumont. (If his name rings a bell, it’s probably because there’s a state park in East Texas named in his honor.)

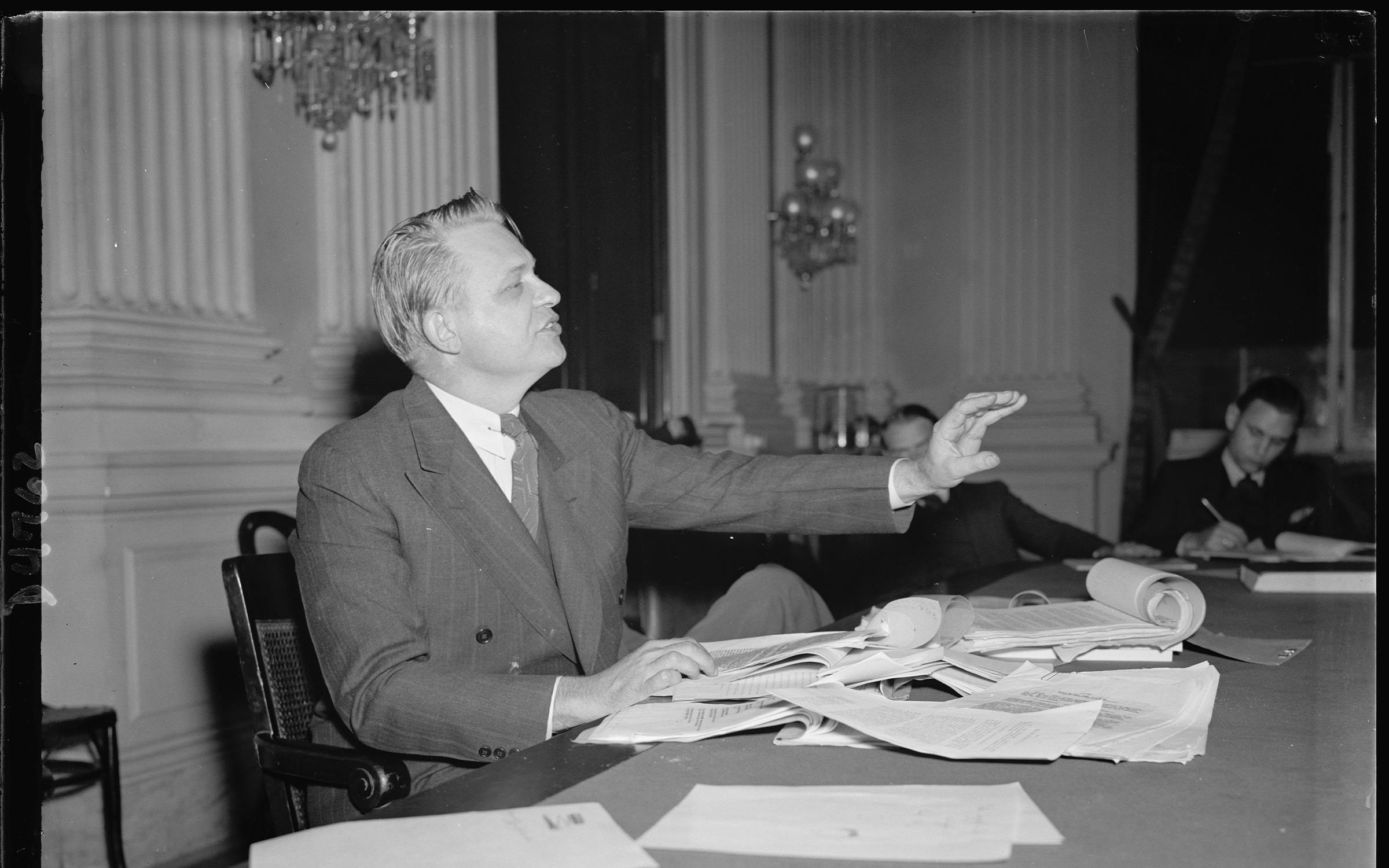

Dies was a masterful politician who pioneered a culture war playbook still in use across Texas, and the nation, today, writes James Shapiro in his fascinating new history, The Playbook: The Story of Theater, Democracy, and the Making of a Culture War. Dies learned to attack the content of the plays, whose scripts, he argued, were subversive, Communist, offensive, or otherwise un-American. Bent on achieving a national reputation through theatrics of his own, he led the House un-American Activities Committee well before Joe McCarthy’s Red Scare and made the Federal Theatre Project his first target. He also pioneered at least three broader, now pervasive culture war techniques: race-baiting, goading the press, and ignoring legislative norms—techniques that have since, as Shapiro puts it, “coalesced into a right-wing playbook.”

Dies wasn’t inherently anti-theater. He’d even been drama club president in his school days. But he was hard to pin down. Early on in his political career, Shapiro writes, a critic noted that “Martin Dies seems to have expressed almost every point of view at least once.” Still, in Shapiro’s characterization, although “Martin Dies would harden into an ardent anti-Communist in the years to come . . . in the summer of 1938 he wasn’t one yet.” While he was “an opportunistic, America-first, racist politician with few scruples, for whom power and popularity mattered more than ideology . . . the Federal Theatre embodied pretty much everything he despised: unions, liberals, foreigners, intellectuals, and promoters of racial equality.” Dies’ attacks on the program captivated the media. Coverage of his committee received more than five hundred column-inches of space in The New York Times alone during the months of August and September 1938.

The Federal Theatre was vulnerable to criticism because, as Shapiro reveals through discussions of five of its most significant productions, it largely tried and failed to walk a line that might have helped it survive while remaining artistically vibrant. The politics of its shows were too aligned with FDR’s policies to outlast his administration, not conservative enough (especially in terms of racial integration) for Dies, and not ambitious enough for the left. Still, its artistic experiments offered new visions of what American theater and life could be.

Perhaps the most notable production was the so-called Voodoo Macbeth, set in nineteenth-century Haiti and performed by an all-Black, Harlem-based cast. It drew 120,000 total audience members and spurred much critical engagement. In his account of the show’s creation, Shapiro cuts through the myth-filled accounts spread by its director, the young Orson Welles, and John Houseman, the show’s producer, to foreground the essential contributions of the show’s choreographers, Asadata Dafora and Abdul Assen. The production went on tour and came to Dallas during the Texas Centennial Exposition, where it played for ten nights. Jesse O. Thomas, who was in charge of Black participation at the event, proudly reported: “We had the play Macbeth with a Negro cast, in the Band Shell . . . Whites and Negroes sat on the same floor.” But press accounts reveal this achievement may have been symbolic rather than substantive, as white Texans were largely unwilling to engage with the show. They could tolerate Black actors in some roles, but not productions of Shakespeare. John Rosenfield Jr., who panned the production in the Dallas Morning News, called it “something to be seen if only to be despised.”

Shapiro’s narrative begins in medias res, during the raucous congressional hearings of the Dies Committee (as the House un-American Activities Committee was called during the six years that Dies was its chair). After the first week, headlines across the nation echoed allegations that the Federal Theatre was “Red Infested.” The public was barred from these hearings, making the press Dies’ only audience. Mixing in photo opportunities with his young son wielding the gavel to keep reporters entertained, he kept a fresh stream of accusations coming, so the press wouldn’t have time to investigate unsupported allegations. He and his fellow congressmen, sensing a media opportunity, performed dramatic readings of scripts they wished to decry as obscene (such one containing the phrase “God damn”). While Dies wove a trap for the witnesses defending the Federal Theatre, asking questions he already knew the answers to, Congressman Joe Starnes of Alabama (a member of the Dies committee) put his foot in it, asking when the sixteenth-century dramatist and contemporary of Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, came up, “Is he a Communist?”

Flanagan, the Federal Theatre’s director, was only allowed to give limited testimony, and not until December, five months after the hearings began—but in Shapiro’s account, her competence and vision shine through. When Dies attempted to label Federal Theatre plays concerned with social advocacy as propagandistic, Flanagan countered that they were, but the propaganda was pro-democracy: “Propaganda, after all, is education.”

While Flanagan’s rhetoric was deft, there was little the Federal Theatre could do to save itself. For months, the Roosevelt administration had instructed Flanagan not to speak publicly, and as Dies’ media-fueled popularity had swelled, the damage had been done. In June, a bill terminating funding for the Federal Theatre passed 373–21. Roosevelt grudgingly signed the bill into law on June 30, 1939, and all Federal Theater employees were laid off July 1. No member of the Dies committee had ever seen a Federal Theatre production.

In this century, attacking the politics of plays you’ve never seen remains a familiar tactic. When the Public Theater in New York presented Julius Caesar in 2017 with a Caesar who looked like Donald Trump, even the completely unrelated Shakespeare Dallas received threats (likely from Texans who emailed the first Shakespeare in the Park organization they found in a web search, rather than the intended target of their outrage).

In February, Keller ISD canceled a high school production of The Laramie Project (an anti-homophobia play that documents community reactions to the murder of Matthew Shepard), but then backtracked and allowed the show to go on. Earlier that same school year, students in Sherman ISD were barred from performing roles that did not conform to their respective sexes assigned at birth in a production of Oklahoma!, until the ban was lifted after a public outcry. And in June, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, whose other legislation has inspired copycats, vetoed all state funding for the arts in Florida under the rationale that some theater festivals have “sexual” content. In doing so, he seems to have taken a page directly from Dies’ playbook.

It’s impossible to know how the country might have been different if the Federal Theatre had survived. Perhaps theater would be a bigger part of American life. Today, the number of adults who reported seeing a musical theater production in the previous year has fallen from about 17 percent in 2017 to 10 percent in 2022, and the number for nonmusical plays is even lower. Meanwhile, the National Endowment for the Arts’ 2022 appropriation of $180 million constituted only about 0.003 percent of the federal budget.

Dies’ un-American Activities Committee succeeded in dominating headlines, but avoided real dialogue, and accordingly represents America at its worst. The Federal Theatre, on the other hand, staged plays on social and political issues, sparking public conversations that could inform and change minds at a time when fewer than one in five American adults had finished high school. While Dies may have helped author the culture war playbook that remains in use today, this history doesn’t provide an easy answer about where the current culture wars will end. It indicates, however, that “in the absence of a return to dialogue,” as Shapiro contends, “there is no end in sight for our culture wars, just a weakening of our democracy.”