I awoke last Friday to learn that I had been conscripted into the fracking wars. It wasn’t my choice, and it wasn’t the first time.

Earlier in the week, Donald Trump’s presidential campaign had released a thirty-second ad in Pennsylvania, which is the second-largest natural gas–producing U.S. state (behind Texas, of course). The gist was that his Democratic opponent, Kamala Harris, would ban fracking all together if she’s elected. Harris says that’s not true, but as the adage goes, truth is often the first casualty of war.

“Trump would protect clean energy fracking and the jobs it creates,” the campaign video’s voice-over intones, while text on the screen declares that fracking “tech is powering a clean energy shift.” This quote is from the headline of a Texas Monthly story I wrote in 2021.

To the communications consultants who put this message together, I have some notes: I’m a Pennsylvanian by birth and Texan by choice, and I’ve spent much of my adult life reporting and thinking about fracking. I’ve hung out with fracking crews and befriended the engineer whose work laid the groundwork for the fracking revolution. I wrote a book about it, which was when my reporting was first dragged into the rhetorical battles over fracking. I’ve been accused of being too friendly to, and too critical of, the technology.

I have no idea what the Trump ad means when it says “clean energy fracking.” The video seemingly implies that busting up subterranean rock to produce natural gas from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale constitutes “clean energy fracking.” Natural gas, when extracted and processed correctly, is cleaner than coal or oil, but it’s hardly “clean.” Producing and transporting gas can release a lot of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. And natural gas production also wasn’t the focus of my quoted article.

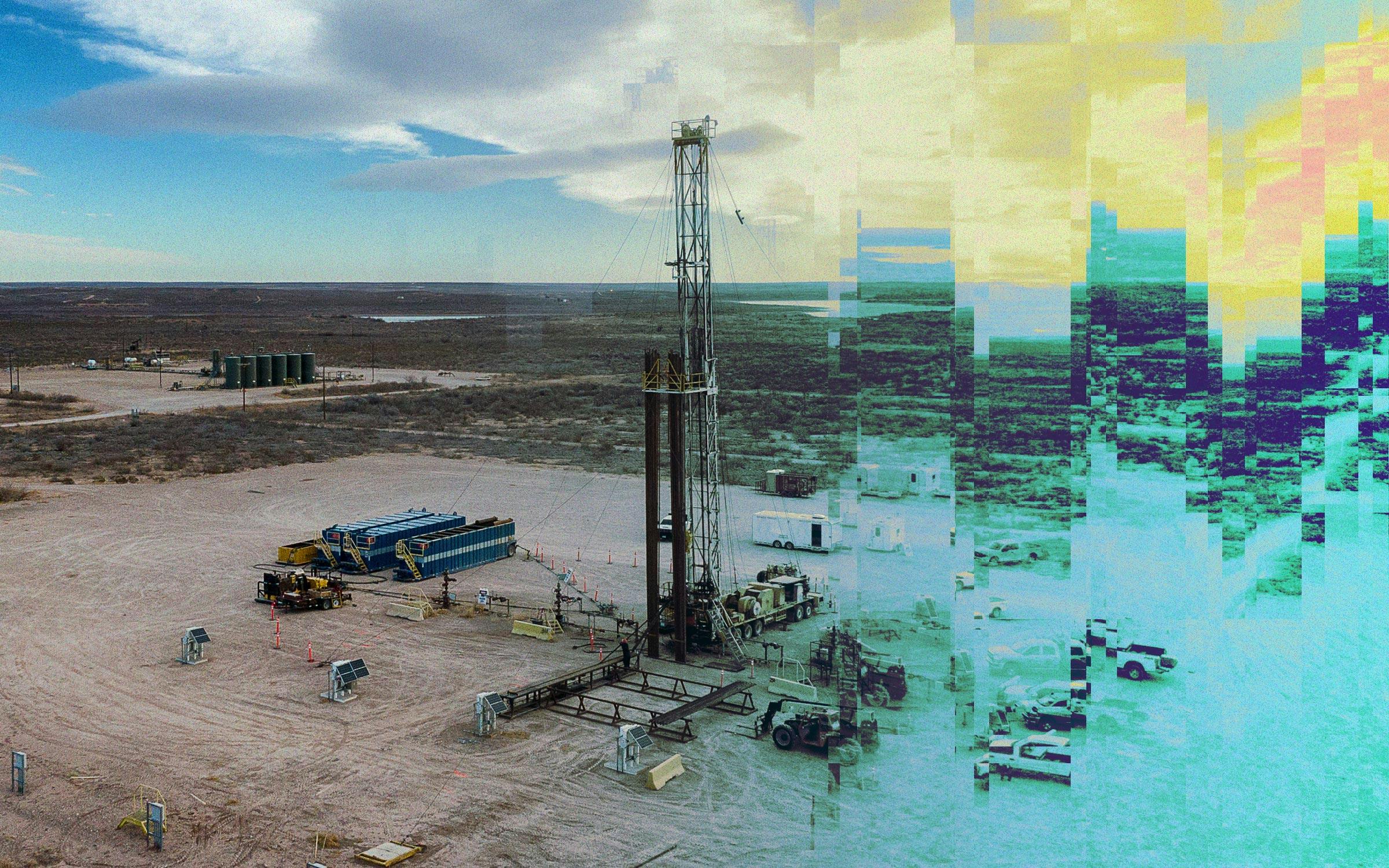

Fracking is a tool that continues to evolve. Back in the 1860s, it was common to drop a stick of dynamite into a newly drilled well in an attempt to create fractures that would allow more oil to flow from the earth. Fast-forward to the late 1990s, and ingenious engineers in Fort Worth figured out how to fracture super-dense shale to free the locked-away natural gas.

Another decade passed before fracking was successfully applied to shale formations that held oil and condensate. Now, fifteen years after that, another generation of engineers is devising new uses for fracking. They’re breaking open rock formations thousands of feet underground to create spaces in which they can heat up injected water to run advanced geothermal power plants—it’s called “pumped-storage hydropower.” These clean energy entrepreneurs are using fracking technologies to create a lower-carbon future. Many of the negative environmental effects of fracking for oil and gas—such as a sizable uptick in earthquakes—result from the associated wastewater disposal wells, which aren’t an issue for these geothermal operations.

While some environmentalists may wish Harris had maintained her 2019 position, which called for a fracking ban, new uses for the technology make it clear that such a simplistic stance may be unwise. That’s the case even if you set aside the economic and security benefits to Texas and the United States of the reduced dependence on foreign fossil fuels that was enabled by the advent of modern fracking.

Here in Texas, fracking is proving to be a versatile tool. It isn’t solely good or bad, any more than a hammer or a knife is good or bad. Fracking’s future is still being written. Cindy Taff, chief executive of Houston-based Sage Geosystems, said her company is working on a new way to generate electricity from carbon dioxide stored in fracked rocks. “Where other companies are sequestering CO2,” she said, “we could bring it to the surface, create electricity, and put it back into the earth.” She expects to begin testing a pilot three-megawatt carbon dioxide turbine over the next month at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio.

Birol Dindoruk, a professor of petroleum engineering at the University of Houston, says he is excited to see what new uses can be found for fracking technologies. “There might be ways we are using fracking that we are not imagining it today,” he told me.

The good news is that while politicians wage a media war over fracking, innovative scientists and entrepreneurs are already reaping peace dividends.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.