Sometimes, when I was watching various artificial heart experiments in the basement of the Texas Heart Institute, I wondered if I was experiencing something akin to Thomas Edison’s housekeeper. That is, someone with only a tenuous reason to be in a place where history was being made—or was made today, when it was announced by the Texas Heart Institute that a new total artificial heart, the BiVacor TAH, had kept a Houston man alive for several days. It is, as one of its developers likes to say, the cardiac equivalent of a successful moon landing, a medical breakthrough that could change the way the millions currently suffering from heart failure are treated. If the device is proven to go the distance, it could spell freedom for people all over the world who now cannot get out of bed because their damaged hearts won’t even let them walk across a room.

The news came to me in the form of a text last week from famed Houston heart surgeon Dr. Bud Frazier, who let me know that he couldn’t go to lunch “because I’m with the patient now and no one knows the physiology of pulseless blood flow” as well as he did.

“You should see the patient if I can save him from his doctors,” he joked. A few seconds later, I froze. Frazier can be very elliptical, and I suddenly realized what he was telling me. I texted him a question in return, my hands shaking. “Is this the BiVacor?” I asked. It was.

I had been waiting for this day while my hair turned gray. Back in 2013, I started working on a book about the fifty-year quest to build the world’s first artificial heart. As one well-meaning friend pointed out, it was, at the time, a book about failure. In 1963, the then most famous surgeon in the world, Dr. Michael DeBakey—who made Houston’s illustrious Baylor College of Medicine into a medical powerhouse through sheer force of will—had promised that more than 100,000 people would be walking around with artificial hearts in their chests within a decade. His timetable was equal to that of then President John F. Kennedy, who promised in 1962—at Rice Stadium, no less!—that we would have a man on the moon within eight years. We all know what happened next: The U.S. alighted on the moon in 1969. But decades rolled by and the artificial heart remained, along with a cure for cancer, one of medicine’s holy grails.

Failure after grisly failure followed, some of which, like the human experiment that was poor Barney Clark in 1982, became a national TV sensation. The problem with any and all artificial hearts had long been that the real organ beats sixty to eighty times per minute, about 115,000 times a day—more than 2.5 billion beats in an average lifetime. It is almost a perpetual motion machine—until it isn’t. Up until very recently, no one had been able to come up with a device that could possibly persevere. The contraptions broke down. They required the patient—or victim—to be tethered to a giant machine that pumped while making so much noise that it could induce near insanity.

Now, though, Frazier told me that his team in Houston was working on an artificial heart with genuine promise, a quest to which he had devoted much of his life. At that point, Frazier’s most successful attempt consisted of implanting two left ventricular assist devices put together—a single LVAD being a pretty successful machine that helped weak hearts pump more blood. The dual LVAD, a sorta kinda heart replacement, had even made it to the cover of Popular Science in 2012 and kept a man with fatal organ failure alive for a bit. But it had the jerry-rigged feel of something Rube Goldberg might’ve come up with if he’d been a heart surgeon.

Before Frazier came along, previous iterations of artificial hearts had invariably tried to mimic the organ’s pumping action, including one created in the 1960s in DeBakey’s lab (and that his nemesis, Dr. Denton Cooley, subsequently put in one of his patients without the former’s permission). Frazier often told me that he didn’t think a total heart replacement would be possible as long as inventors continued to imitate the heart’s pumping action, because pumps wear out. A patient in that situation would either need replacement surgery or a transplant, which come with their own set of problems. Frazier suspected that something like the spinning action of a turbine was the answer. The Wright brothers, he liked to say, didn’t get in the air by trying to imitate a bird in flight.

The stakes of his work could not have been higher. Heart failure currently kills 6.2 million adults in the U.S. and 26 million people around the world. Those numbers suggested sizable interest in a book about heart disease, I thought. And eventually Mattress Mack entered the picture as a funder—he had lost a brother to heart disease, despite Frazier’s efforts to save him—resulting in a character lineup from central casting: Bud Frazier as a West Texas philosopher-savant and Vietnam vet; his partner, heart surgeon Dr. Billy Cohn, a zany inventor who could sell ice to those proverbial Eskimos; and, finally, the super rich furniture salesman who kept a couple tiger cubs as pets.

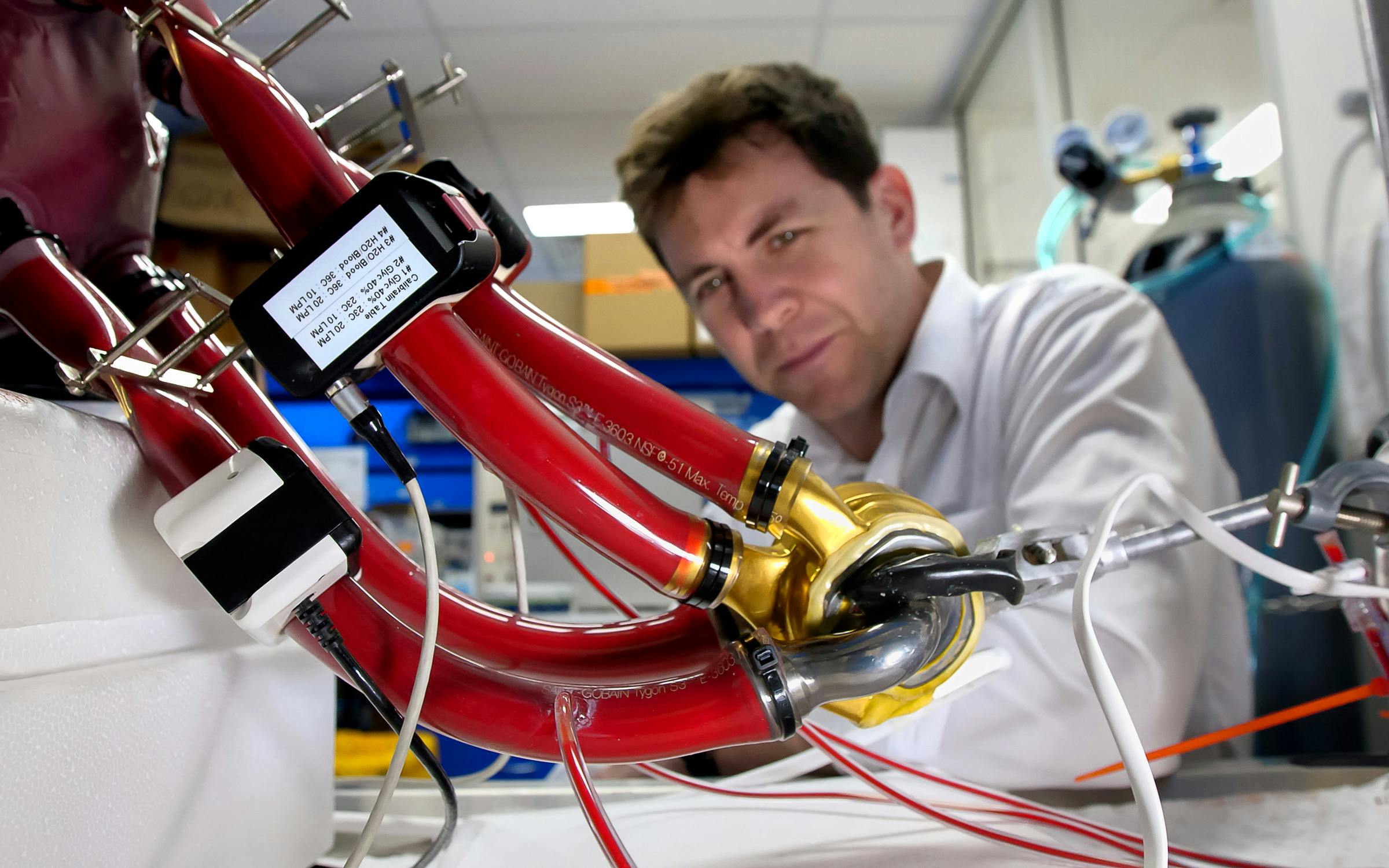

And there was one more thing: It so happened that in 2011, a young Australian named Daniel Timms had shown up in Houston with an alternative he had been carrying around in a backpack. His device had one moving part and was the size of, say, a sweet orange from the Rio Grande Valley. Timms had talked his way into seeing Cohn, who at first wasn’t particularly interested in talking with a kid who needed a shave and clean clothes, and kept his invention wrapped in a rag in a flimsy backpack. But then Cohn got a look at what Timms was carrying, the precursor to what is currently described in a Texas Heart Institute press release as “a titanium-constructed biventricular rotary blood pump with a single moving part that utilizes a magnetically levitated rotor that pumps the blood and replaces both ventricles of a failing heart.” At that moment, the dual LVAD that Cohn had been working on with Frazier was consigned to, if not the dustbin of history, then one of those museum shelves that show the development of an idea in midstage. In Timm’s invention, Billy Cohn and Bud Frazier, it could be said, had the Holy Grail within their grasp.

Probably to their deep regret, Cohn, Frazier, and Timms let me hang around as they improved upon the original BiVacor. One day in 2014 I was in the animal lab in the Texas Heart basement, where there was a healthy-looking calf on a treadmill. Timms stood at a control panel while everyone else stood around staring at the calf. No one in the room seemed to be breathing, except the calf, who began moving along the treadmill while Cohn offered it a carrot. The calf kept walking, trying to reach the snack, with an expression that suggested it was trying to figure out what the big deal was. Then it was over. Frazier told me to put my head to the animal’s chest, which I dutifully and quickly did, because I kind of intuited that no one was all that happy to have a journalist in the room.

I pressed my ear into the calf’s soft hide and heard . . . nothing. Nothing that sounded like the lub-dub we are all accustomed to, nor did I feel any pulsing rhythm against my ear. There was just a very soft whirring sound I heard after someone handed me a stethoscope. That was when I knew what Thomas Edison’s housekeeper might have felt if she’d come into a previously dark room set aglow by a single bulb.

My deadline for the book was in 2018, and I met it with the best ending I could summon at the time. It was not a story of failure but of persistence—Frazier had devoted his life to a singular pursuit. So, for that matter, had Timms, and I never doubted the team would succeed. Still, Frazier had reached his eighties, was white-haired with worn-out knees, and he often told me he worried he wouldn’t be able to stay above ground long enough to see the end. Still, he kept the faith. Every time I saw Frazier over the ensuing years, he told me they were six months away from implanting “the pump” in a person. (Why they called the BiVacor a pump when it doesn’t pump is, I guess, force of habit.)

Well, Frazier did live to see it. There were a lot of FDA hoops to jump through and a ton of money to raise. And a lot of calves gave their lives so that humans might live. But for the first time ever, the BiVacor heart now sat in the chest of a local man who otherwise would have died from heart failure. Then he got the heart transplant that is keeping him alive today.

The device is still experimental and is being used first as a “bridge to transplant.” There will be more human trials, but, very likely, one day BiVacors will sit on hospital shelves, waiting to be put into service in hospitals all over the world. In the meantime, Frazier will be found at the bedside of every BiVacor patient, watching and waiting.

Pumps wear out, but some people just don’t.

When you buy a book using this link, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, a portion of your purchase goes to independent bookstores and Texas Monthly receives a commission. Thank you for supporting our journalism.