Editor’s Note: This report is part of “Seeds of Distrust,” an ongoing investigative collaboration between Lighthouse Reports, the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, the Texas Observer, palabra, and Puente News Collaborative.

Arvin West is the iconic borderland sheriff in far West Texas’ deeply rural Hudspeth County. His distinctive drawl and no-nonsense policing have made him a darling of conservative politicians and fellow sheriffs nationwide, who are convinced that migrants pose a threat to the upcoming presidential election and democracy itself.

West is a Democrat-turned-Republican. In 2005, he helped start the Texas Border Sheriff’s Coalition. His rising national profile helped him lobby for multi-million-dollar grants so local law enforcement could fight powerful transnational smuggling organizations.

But these days, West is evolving. He pushes back against far-right rants of ultra-conservative politicians and so-called constitutional sheriffs about threats migrants might pose to the November 5 vote. He speaks forcefully about being a local sheriff in a border county that’s always been home and where Latinos (including those in his own family) are not enemies but voters who’ve kept him in office—most recently in an unusually tough primary election campaign earlier this year.

Just ahead of a monumental presidential vote that pivots around migrants and immigration, West is more measured and reflective. He looks at his recent years raising hell about the border and underscores why he’s taking a different tack: It’s not so much that he’s suddenly stopped being a conservative and tough on border security. He’s concerned that too much talk about the border and the people crossing is not just extreme, but deepening political divisions. He also says he’s fed up with politicians distorting issues of immigration and drug trafficking and playing ideological favorites with policing grants and incentives.

A former football middle linebacker in high school and the Friday night play-by-play announcer for Sierra Blanca ISD, West is characteristically straight to the point about his growing frustration with political gamesmanship on immigration that has distorted the truth about the southern border.

Most folks don’t understand the border and its people, he says, adding that many spread misinformation about migrants while politicians earmark grants to locals who parrot claims of immigration chaos and migrants usurping U.S. jobs and public benefits.

“I know what works for Hudspeth County. I know what works on the border,” West says. “And I don’t care who wants to come across that border to work. … Put a checkmark on their forehead. … But if they want to bring drugs in, if they want to come (to) commit crimes here, then we need to stand hard on that.”

After an incursion by what he calls a “Mexican military” onto U.S. territory in January 2006, the media spotlight turned to West. He spoke in colorful language about perceived threats of immigration and being outgunned at the border by smuggling cartels.

The attention changed Sierra Blanca, a small community in the heart of Hudspeth County. The town hugs Interstate 10 southeast of El Paso and has no traffic lights. It does have a declining population, now around 800, surrounded by a county of about 5,000 people. Sierra Blanca is sandwiched between the larger town of Van Horn and a notorious U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint whose drug-sniffing dogs are credited with bringing down—on possession charges—rap star Snoop Dogg, songstress Fiona Apple, and country singer Willie Nelson. They’re among the many caught by the “checkpoint to the stars,” jokes Oscar Carrillo, West’s longtime friend and sheriff of neighboring Culberson County.

Carrillo says the celebrities often found themselves jailed briefly alongside migrants held in Hudspeth County jail for violating local laws or not possessing documents. (West recalls that he and Nelson spent most of his time in custody talking about performing at a future sheriff’s conference in Houston.)

Drivers used to zoom through the county, unless they needed gas or craved a bite at Delfina’s Mexican restaurant. More recently, throngs have flocked to the area for a glimpse of Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origins rockets, flaring into wide-open skies northeast of Van Horn.

The community has also gained favor among media and conservative politicians who’ve come for West’s border security witticisms. While his immigration rhetoric has moderated, there are still days when West’s turf is popular with social media influencers taking selfies, and fear-mongering about the porous border, with the CBP checkpoint or desert hills as backdrops.

West doesn’t shy away from hard talk about the border, but he says he’s also tried to keep extremists and militias well away from Hudspeth County.

Others have been welcomed. At the peak of his celebrity, West deputized headliners like actor Steven Seagal. He accepted invitations to address lawmakers in Austin and Washington, D.C., where he lambasted the federal government for “abandoning the border.” He shared dramatic stories about a drug war that came to his county, about that Mexican military invasion, and about the constant threat of terrorists crossing the border. He warned reporters about Qurans he discovered in a motel.

His words on the border and crime sometimes aligned with the anti-immigration canon of sheriffs in the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA). West says he was supportive of the group’s insistence that sheriffs are the ultimate lawmen in their counties, but he disagreed that the authority allowed them to defy the U.S. Constitution and pick and choose the laws they’d enforce.

“I took an oath to support our nation’s Constitution,” he says. “Other than that, you know, right is right and wrong is wrong.”

(CSPOA advocates such things as leapfrogging federal statutes in favor of state and local intervention in immigration enforcement.)

While he sometimes rode with the constitutional sheriffs—and not always at the same pace, he says—he was making old friends increasingly uncomfortable at home. Bill Addington, chairman of the Hudspeth County Democratic Party and West’s neighbor, has consistently voted for his lifelong Republican buddy. “He’s a thoughtful person,” Addington says. “That’s something the national media doesn’t get.”

But Addington has criticized West’s portrayal of the border, which he likens to a political “feeding frenzy. The more you bash the border, the more resources you may get.”

West “has toned it down these days,” says Carrillo, the Culberson County sheriff, referring to West’s past rhetoric.

West and Carrillo go back more than 35 years, to when West was a chief deputy in Presidio County and Carrillo was the police chief in Marfa. Back when they mused about someday becoming sheriffs.

Carrillo says he’s long admired West’s blunt talk.

But unlike West, Carrillo keeps a low public profile, especially on politics, given the divisive times in Texas. He quietly supported former U.S. Representative Beto O’Rourke in a failed bid to unseat Governor Greg Abbott, and today he backs the campaign of Representative Colin Allred, who’s in a close race against U.S. Senator Ted Cruz.

Culberson County, population 2,196, is another flashpoint in a polarized debate about immigration. The county seat is a two-hour drive from the Mexican border, following a quiet highway that slices through a wind-swept desert interrupted only by the touristy Prada Marfa, a quirky shoe-store-as-art installation near the tiny town of Valentine.

Culberson is surrounded by the equally rural Hudspeth, Jeff Davis, and Presidio counties. They’re connected by busy commercial highways and picturesque roads adjacent to the vast Chihuahuan Desert. Too many migrants die there each year from heat stroke, dehydration, or a winter freeze, left behind by smugglers who favor the corridor’s isolation.

“Sometimes we forget we’re dealing with human beings,” Carrillo says.

Carrillo sees no end to the debate about migrants, especially their smugglers, often found speeding along the same highway on their way to Interstate 10 and big cities beyond. Like West, Carrillo blames the U.S. district attorney’s office for not holding the true criminals accountable.

“Why are we putting ourselves at risk, the public at risk, if at the end of the day, nobody’s gonna get prosecuted?” he asked. “They’ll deport the deportable, but there’s no real accountability.”

Carrillo’s “aha” moment came after the mysterious death of Border Patrol agent Rogelio Martinez in 2017 east of Van Horn.

Martinez and a fellow agent were found in a culvert area with traumatic head injuries. “None of the more than 650 interviews completed, locations searched, or evidence collected and analyzed have produced evidence that would support the existence of a scuffle, altercation, or attack,” according to an FBI statement at the time.

The tragedy catalyzed the likes of the National Border Patrol Council, which sought more federal money for agents and technology. The union initially insisted Martinez had been bludgeoned with rocks, an unfounded allegation that became fuel for Trump’s clarion call for a border wall.

Carrillo was one of the first responders at the scene of Martinez’s death. He suspected, from the start, that the incident was probably an accident–a position that won him scorn from conservatives and the Trump administration.

“(It seemed) facts no longer mattered,” Carrillo recalls. Asked whether this incident was his turning point, he added, “Yeah, like we were going too far, (following) this rabbit down the hole, yeah.”

Still, Texas law enforcement seemed inclined to get tougher than ever.

Operation Lone Star, the multi-billion-dollar state border enforcement initiative spearheaded by Abbott, deployed 10,000 National Guard troops along the 1,254-mile Texas-Mexico border. Referring to sheriff’s deputies from states including Florida, Ohio, and South Dakota who spent off-duty time supporting local deputies, Carrillo smirked and asked, “What do they know about the border? It’s just a show, a circus, and we’re the starring characters.’’

That didn’t stop Carrillo, the Democrat, from signing on to Abbott’s border disaster declaration.

“Not for politics. I’m just practical. We need to be reimbursed for more than $300,000 we spent on the migrants who’ve died (crossing the border).”

But the money never came.

West says his department once thrived on outside funding for equipment and training and government grants that underwrite Texas’ defiance of federal immigration law and its rogue brand of border enforcement.

West said the grants were a mixed bag, at best. People lived high and low, he recalls. Money, he says, with a slight grin, made even his deputies do crazy things. When money flowed, deputies worked overtime, enough to make the family happy with things like new cars. Then, the money dried up, leading to divorces, unhappy marriages, and negative work environments.

Moreover, the cost of the extra policing isn’t fair to local taxpayers, he says.

“For 90 days, I feed them. I take care of them, take them to the doctor, whatever they needed. … Then the district judges bonded them out on personal recognizance to never see them again. … Why should I stack my jail with these people, and then they never get prosecuted? It just doesn’t make any sense.”

West grows visibly angry when he talks about state funding he says is now owed to Hudspeth County for the extra patrols he assigned to go after unauthorized migrants and suspected traffickers. But compensation for that has been slow or non-existent, he adds, while other sheriffs, sometimes hundreds of miles from the border, enjoy greater financial support from the state and police organizations that used to donate to Hudspeth County.

“We’re not any closer to stopping this,” West says of border lawlessness. “And then you compound that to the next level, where I’ve got my guys out here running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, arresting people and trying to bring them to justice. … We arrest them, we bring them to jail, and there is no prosecution. You have to ask yourself: Is this a game? A charade?”

Looking back at decades of screaming and shouting about more boots on the ground, walls, fences, drones, constitutional sheriffs, more state troopers, and National Guardsmen, Carrillo says he has mixed feelings about his and West’s place in the issue. Carrillo is all about security for his constituents, he says, but, “It’s been a whole lot of failure. … We’ve only inconvenienced people and for what, a grant? Some TV airtime? It’s a sick game, and there is no end in sight.”

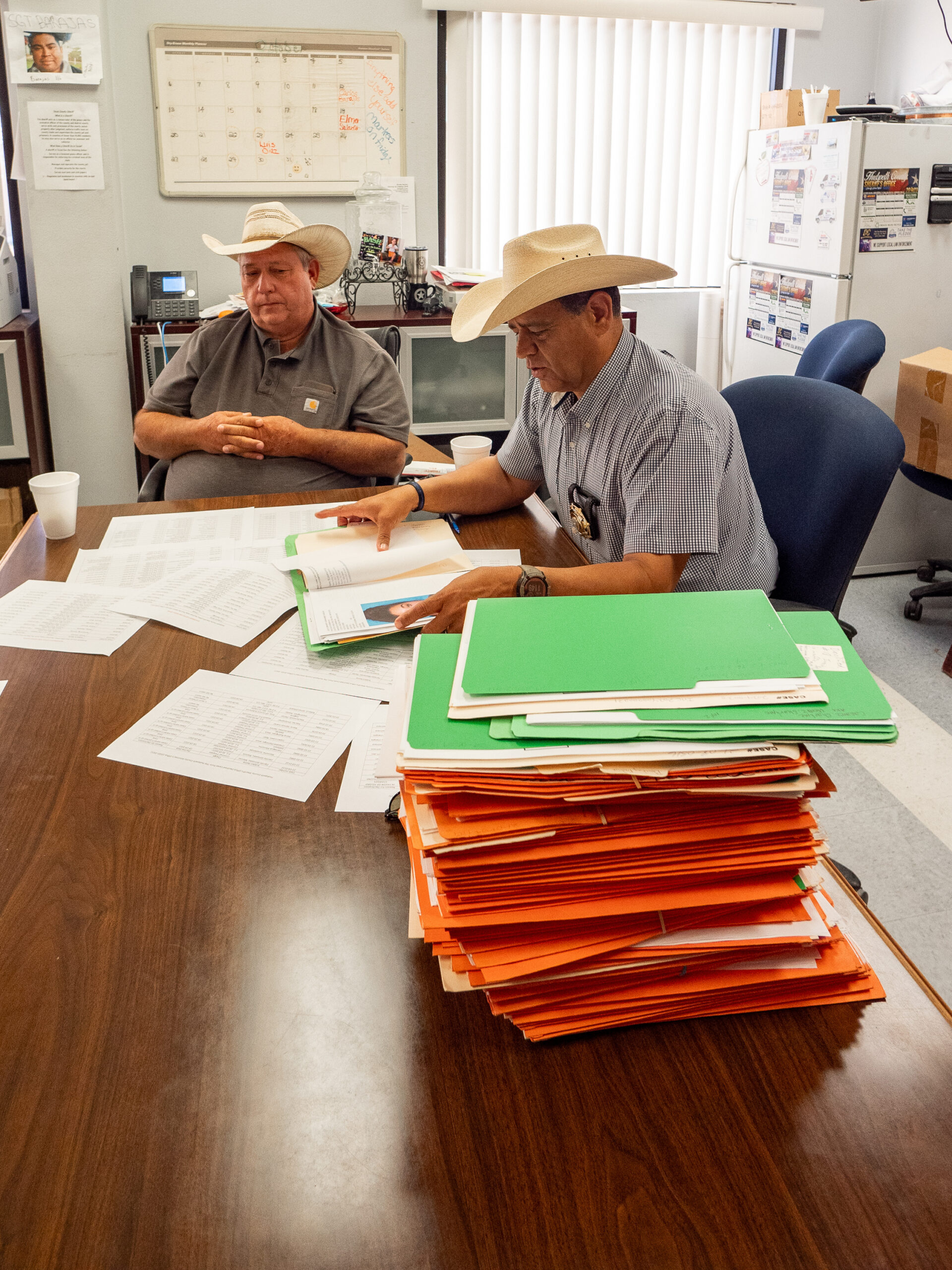

Recently, the two sheriffs met in the Hudspeth County sheriff’s office and displayed hundreds of case files, some 300 misdemeanors and felonies that their offices filed over the past two years. All were dismissed by county prosecutors.

“It’s embarrassing. It’s frustrating. It pisses us off,” said Carrillo, adding he feels “burned.”

“It’s bullshit,” adds West.

El Paso Public Defender Kelli Childress blamed “chaos” for the dismissals and acquittals. “That’s inexcusable.”

The El Paso’s District Attorney’s office, responsible for overseeing prosecutions of felonies in Culberson and Hudspeth counties, did not respond to multiple phone calls from the Puente News Collaborative regarding the allegations.

The dismissals deepened the bond between the two sheriffs.

“He’s a diehard Republican, and I’m a diehard Democrat. We’re totally political opposites, but … we know we need to work together,” he says. “We have … common highways. We got common criminals. We have common challenges. You know, the terrain, the border, todo. And … when I can’t get the resources from the feds to come in to help or the state, you know, this guy’s my constant. … I mean, we have to. Our communities are so isolated we have to turn to one another for support and resources. There’s not much else between us.”

West’s ire becomes a lecture on the nuances of the border, the complexities that are too often overlooked.

To be clear, West insists he still leans hard toward tough border enforcement. But he now also emphasizes his full name: “Arvin West Ramirez, a GMC: a gringo, Mexican combination,” he says, noting that his mother is Mexican and his father is “a gringo.”

His roots run on both sides of the border. And though he once toyed with becoming a Border Patrol agent, he discarded the fleeting thought. “I didn’t want to be chasing my own primos,” his family members from the Mexican side of the line.

Border problems are more complex than just migrants crossing, he adds.

There’s been too much conflating of the drug and immigration issues, he says. “It’s a mistake. … The drug aspect we all know, it’s horrible, terrible. It kills people. … For 42 years, I’ve fought this war on drugs, and we ain’t no closer (to winning) than we were 42 years ago.”

Making things worse, he contends, are federal and state officials who don’t offer real solutions while they use the border as political theater.

Trafficking must be stopped, West insists, but politicians have turned that into a talking point that makes immigration loom as a bigger threat to democracy.

Is he worried about noncitizens voting this November or any past November?

“No, no. That young lady sitting over there,” West says, pointing to a woman sitting at a desk in the county office, “She’s our voter registrar here, and she’s pretty good on it, she stays on it, and (voter fraud and non-citizen voting has) never been an issue in this county. … You know our American system may not be the best, it may not be the greatest system, but it’s the best system in the world.”

And West is quick to add that he has respected, and will respect, the outcome of federal elections.

“If President Trump loses, he loses. I mean, simple as that.”

“There are some radical sheriffs out there,” he adds. “There is no reason to even try to sugarcoat it or deny it. … But why? … All you’re going to do is cause ill feelings. Your job, our job, my job, is to protect the safety of the citizens.”

West says he’s talked with CSPOA founder and former Graham County (Arizona) Sheriff Richard I. Mack.

“He talks about things that we need to do to protect our citizens from the federal government. I agree with that. I agree with that wholeheartedly. But on the same token, we don’t resort to violence or anything like that. … When I get that badge on, I’m only here for my citizens,” West says.

But the extreme talk leaves West sure that he’ll follow a middle path.

“I think I would classify myself as a very conservative Democrat or a very liberal Republican. Does that make sense? The bottom line is, we’re all Americans. We have to live with each other personally. Let’s get rid of the party system, Republican or Democrat.”

“Let’s vote for whoever we think is the best person. Bottom line.”

West’s practical approach to politics was hardened by a contentious reelection bid against one of his former deputies, Carlos Chaparro–a race he won last spring by a slim margin.

“I love the job … as sheriff,” West says. “And, for lack of better words, what I don’t like is political bullshit. Well, it comes with a job, right? It comes with a job, but it’s getting old, and I … probably don’t have high tolerance for that anymore.”

The post A Lawman’s Change of Heart? appeared first on The Texas Observer.