It was hot, even by Presidio’s standards, when my brother, photographer Justin von Oldershausen, and I pulled up to the Presidio International Raceway last September. We arrived at the racetrack early, and there was no shade or shelter from the sun. It was hot, though it had been raining. The land was green on either side of the road that runs south from Marfa, rare for that time of year. But the rain wouldn’t reach us.

The racetrack appears off FM 170, a single-lane highway that runs parallel to the Rio Grande, here a silty band of torpid water. Past a manufacturing complex for prefab homes, there’s a flagpole with an American flag and the Texas state flag below it. Alex Jimenez, vice president of the drag races, who’s affectionately called “Pumpkin,” told me they want to put the flag of Mexico below the Texas flag. Normally, they’d get at least a half dozen racers from Mexico, but the border had been closed because of the pandemic. (It reopened in November.) Through word of mouth, they’ve attracted racers not just from Ojinaga, the Mexican border town opposite Presidio, but from as far out as Chihuahua City and Delicias. “That’s why we’re called the Presidio International Raceway,” Alex said, gesturing to his T-shirt bearing the name.

The quiet, unassuming border town of six thousand, just west of Big Bend Ranch State Park, started hosting drag races in the early aughts. Back then, officials would shut down a piece of the highway for the races and reroute the highway traffic with cones. Eventually, the town built a real racetrack, which had fallen into a state of disrepair until 2019, when Robert Romero, president of the drag races, and Alex took it over. They rebuilt the whole thing and extended the length of the track. In July 2019, they hosted the first drag race Presidio had seen in more than ten years. Shortly after, though, they were forced to shut down again because of the pandemic. They resumed in May 2021.

The racetrack is two lanes with a starting light in between them. Only part of the 660-foot track is concrete; the rest is made of asphalt. When I asked Jimenez why, he rubbed his fingers together, indicating that money was a factor. They were able to secure a $15,000 grant through the city’s development district, which was enough to pave it with concrete only halfway. As of April, they added another ninety feet of concrete to the track with money raised through private donations, including $2,000 donated by Presidio’s only grocery store.

It is bracket racing, meaning the aim for drivers wasn’t to reach the finish line first. It’s a little confusing in that way. A car that absolutely smokes the one next to it doesn’t necessarily win. Before the races, the competitors determine their individual target times in a series of trials. The goal is to get as close to that time as possible. The car that finishes closest to its target time wins. It’s all about consistency and how quickly the drivers respond to the green light. Souped-up Camaros race against work trucks—it’s all fair game. “Bracket racing is a poor man’s sport,” Romero said. The top three finishers get a trophy, and first and second place receive cash prizes—a percentage of a pool made up of entry fees.

The races are a uniting force. There were folks coming out from Midland and Odessa. They’ve even had a couple Border Patrol agents race, the same ones who police the town. One of them recently crashed into the barrier. Crashes don’t happen often; no one’s gotten hurt yet. “A lot of guys get real nervous competing,” said Adrian Jimenez, Alex’s brother, who helps out at the races. “We’ve got to make sure their car is pointing straight forward, and their tires are also pointing straight forward.”

I heard that a sixteen-year-old girl named Dafny Moreno was racing. It was her fourth time; the last time, she came in second place. “She’s a natural,” Romero said. “She’s good at it.” About 90 percent of the racers are men. They’re hoping more women participate.

“Does she even have a license yet?” I asked Robert. Doesn’t matter, he told me. As long as she’s got a legal guardian present, she can race. Out here, the rules of the road don’t apply.

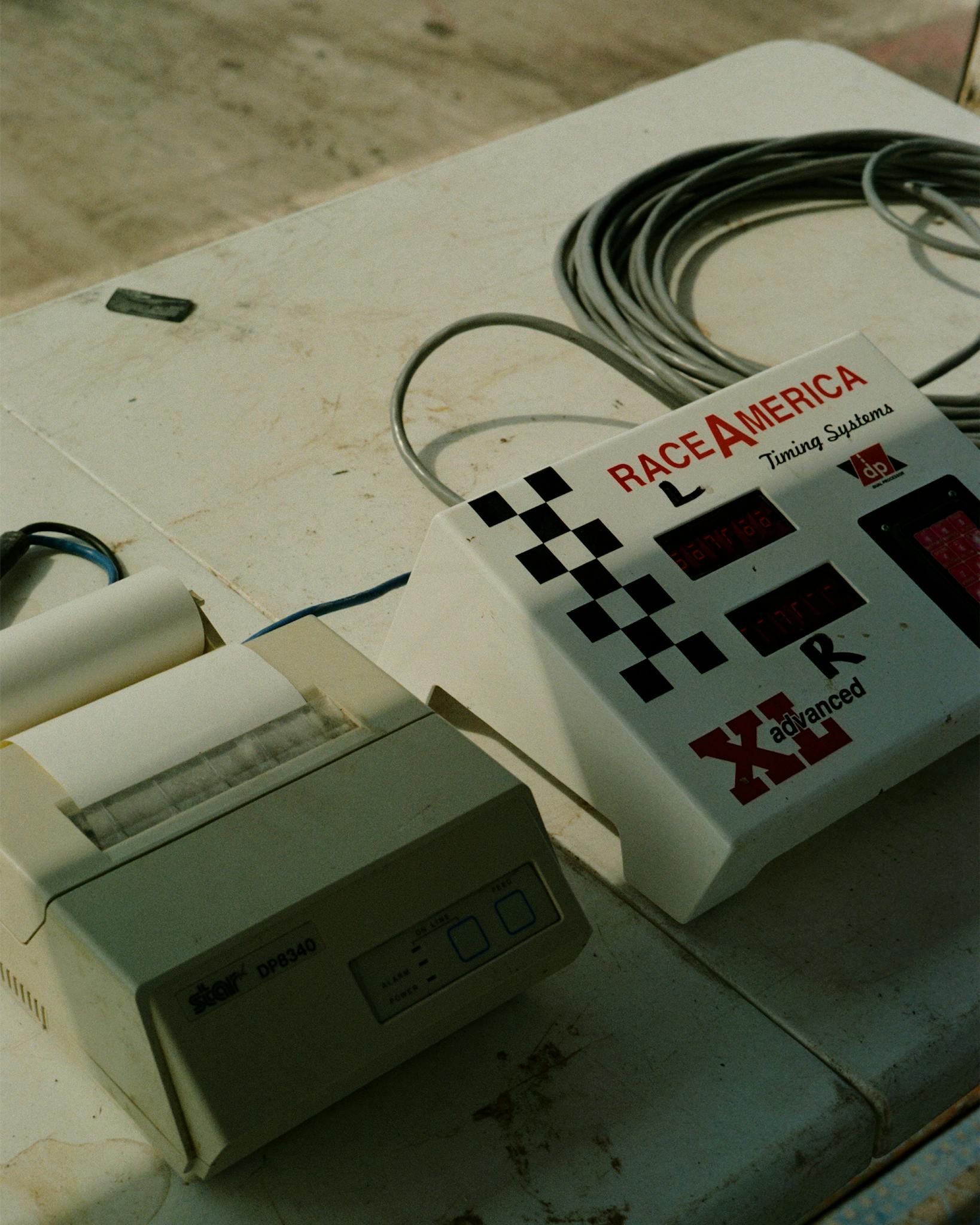

Behind the starting line at Presidio International Raceway.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

The heat wasn’t letting up, so Robert Romero and Alex Jimenez, pictured here, decided to delay the time trials a couple hours. They were worried about the racers’ engines, which could overheat.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

A team looks on as their car races down the track. Before taking off, each racer did a “burnout” at the starting line, spinning their tires in place over water to get rid of any debris. Burnouts also heat up the tires, making them more pliant, which provides more friction. Every time there was a burnout, the tires shrieked and clouds of smoke carried the smell of burning rubber.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

“Time trials start at six, and they’ll show up at eight or nine,” said Adrian Jimenez. “We’re pretty laid-back; we’re not strict like the big tracks.”

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Jonathan Leyva, 17, would be racing for the first time in his mom’s Tesla, parked nearby. “She told me she didn’t want me to,” Jonathan said. He was nervous about it too. His dad, Cesar, was helping him calm his nerves.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Benny Q. Benavidez, 31, recalled going to drag races across the border in Ojinaga as a boy with his father. His dad was racing against a truck called La Cardiaca—”the heart attack.” Nobody thought he’d win. “I can close my eyes and still see it,” he said. “I’ve always been really quiet, but I remember that day I was yelling and jumping.”

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

His father, Benny D. Benavidez, 61, pictured here, is a drag race legend. The elder Benavidez contracted COVID-19 in February 2021. The following month, he had a series of strokes while driving home from the grocery store. By the time the ambulance showed up, he’d had a heart attack. He gave his old race car to his son. He teared up when I asked if he was sad he couldn’t race anymore. “I’ll get over it,” he said.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

View of the track from the race control office above the track entrance. The elder Benavidez recalled paving the old racetrack with a friend. “We worked out here till dark one day pouring this concrete,” he said. “The concrete was so fresh we couldn’t put our cars on it because it would ruin it. So we said, ‘F— it, we’ll just have a foot race.’ I won! He wrecked! He fell and he broke his hand. He had to go to the hospital.”

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Juan Mena was at the races with his grandfather, Jesus Murillo. I found them riding a golf cart around the place. Juan told me his grandfather, who was a welder, used to fix cars too.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

The mayor of Presidio, John Ferguson, was deejaying the event. “Highway to Hell” by AC/DC blared over the speakers.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Men who make up a racing team look on as they wait for their turn to race.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Dafny Moreno in her race car. While I was interviewing the storied sixteen-year-old, a truck pulled up that was filled with her high school friends, who spilled out the windows and cheered her name. I finally got to ask Dafny if she had a license. “I have a permit,” she said.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Folks came out to tailgate with their whole families. They brought barbecue pits and coolers full of beer.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Cars peeling off the start line.

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

“My leg shakes as soon as I get up to the line to get ready,” the younger Benavidez said. “I’m shaking, and then as soon as you pump the clutch it’s just hang on and row the gears. And then it’s over before you even know it.”

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen

Born and raised in Presidio, Tony Arenivas loves the races. He likes that they bring people together, people you maybe haven’t seen in a while. He doesn’t race himself, but he likes to help out with the mechanics. “Usually everybody uses Chevy engines,” he said. “They take más punishment.”

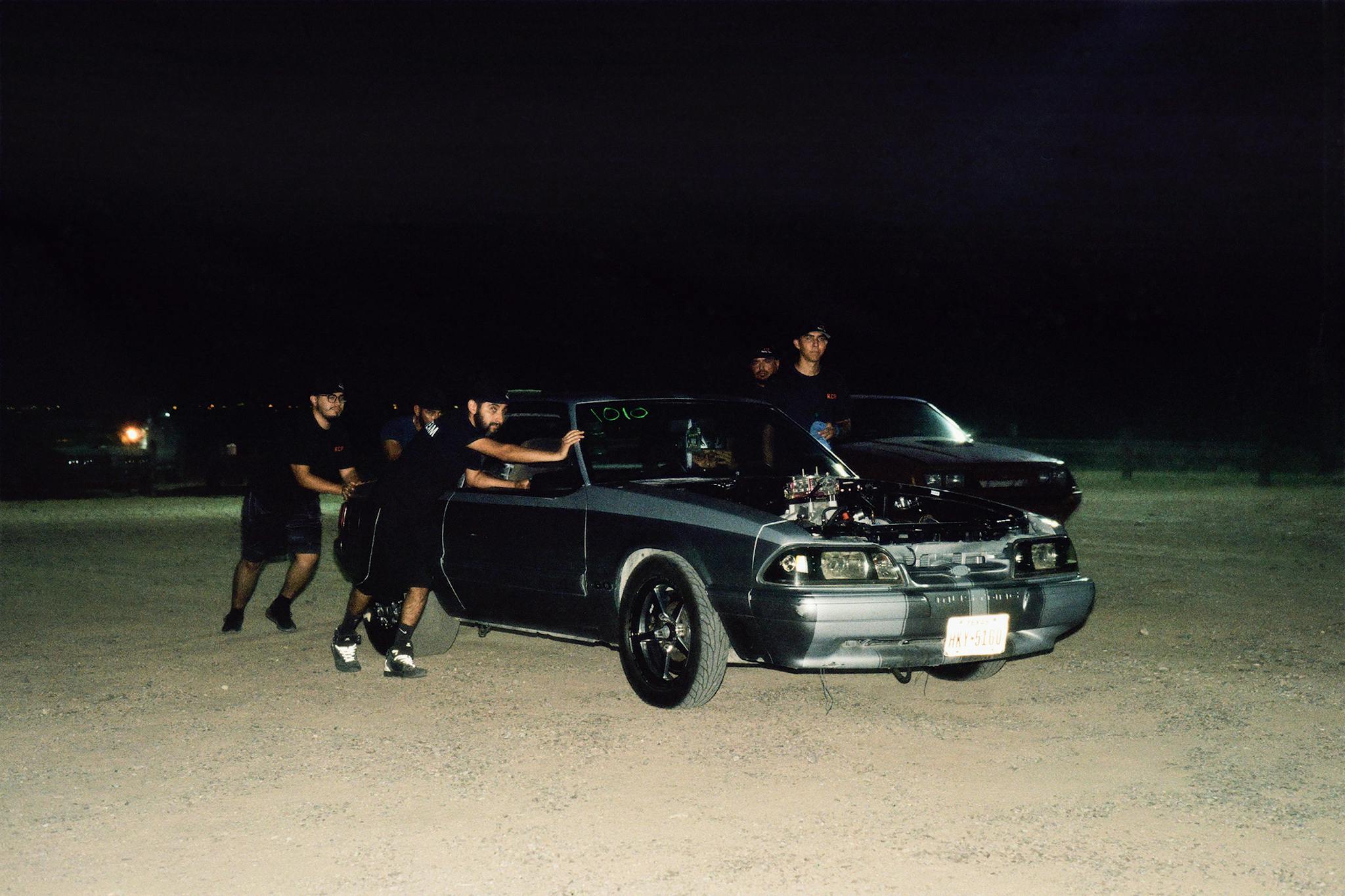

A team pushes its car to the start line. “It’s addicting,” said Jonathan Cobos, who came from Alpine. “You get that adrenaline and you don’t want to stop. It’s hard to get your foot off the gas down there.”

Photograph by Justin von Oldershausen