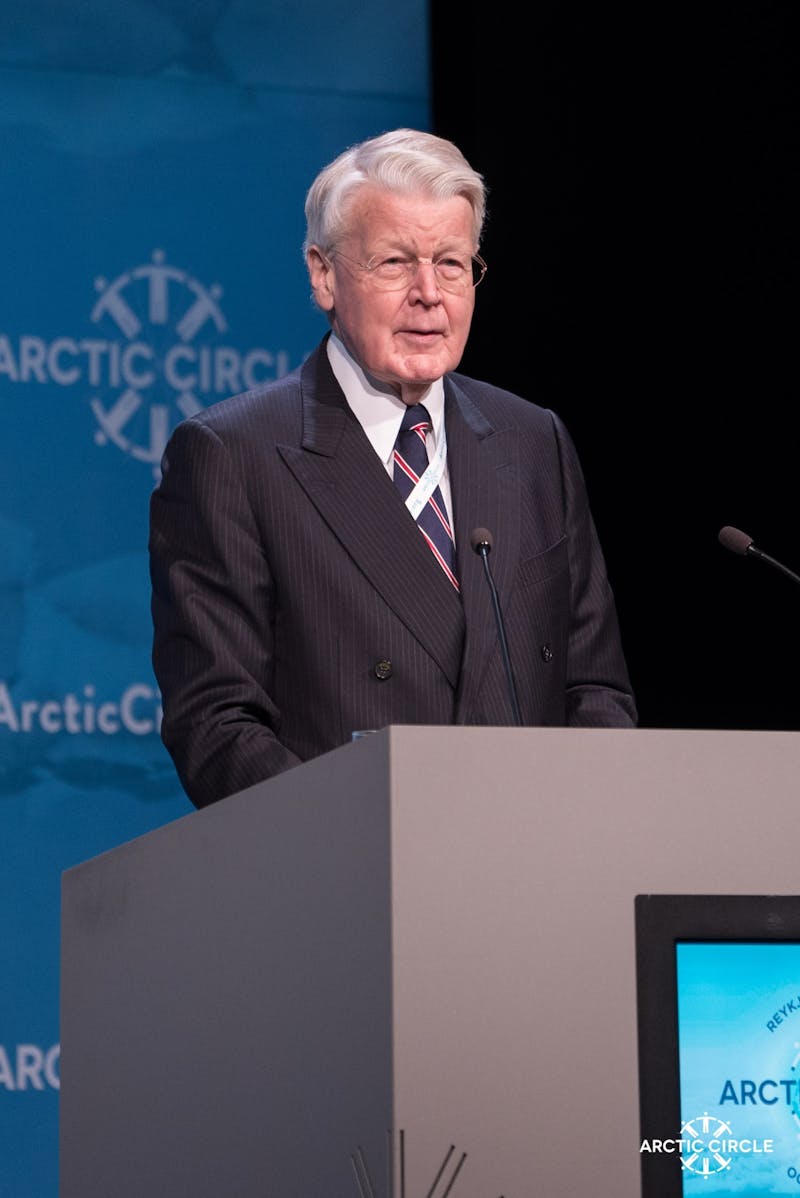

Editor’s note: After 20 years as president of Iceland, Ólafur Grímsson stepped down last year as the longest-serving democratically elected head of state in the world. Under his leadership, Iceland embraced its role on the world stage as a living example of both the impacts of climate change and the promise of climate action. Now as chairman of the Arctic Circle, a network of international dialogue on Arctic issues, and a Lui-Walton Distinguished Fellow at Conservation International, Grímsson is working to advance a new model of social change — one that relies more on mass mobilization than on government decree.

Tomorrow, marchers will gather in Washington, D.C. and across the United States to raise awareness about climate change. Human Nature sat down with Grímsson to discuss melting glaciers, 100 percent clean energy — and the changing nature of political movements and local action.

Question: How is the Arctic experiencing the effects of climate change? What evidence do you see in Iceland?

Answer: In Iceland, we have the largest glaciers in Europe, and we have been studying them for more than half a century. And so we do not need to go to international conferences to realize that climate change is happening. Prior to the Paris climate

conference in 2015, I flew the president of France, François Hollande, in a helicopter to one of our fastest receding glaciers. I let the helicopter land not at the edge of the glacier but where it was when I was born. And then I let the president

of France walk across the black sands and the wet rocks and this area for almost half an hour so that he could personally experience how fast that particular glacier had receded just during my lifetime.

Our neighboring country is Greenland, which together with Antarctica has the largest ice mass in the world. Greenland is half the size of Western Europe. And now you can see fresh lakes and rivers in the ice sheet and various other evidence of aggressive

melting. If only a quarter of the Greenland ice sheet melts, it would lead to a global rise in sea level of about 2 meters, which would be disastrous for all coastal cities in the United States and in fact everywhere in the world.

North of Iceland, we have the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic sea ice has been melting very aggressively, and there is less and less of the Arctic sea ice in the summer. The melting of the Arctic sea ice causes extreme weather patterns in Asia, in China, in

other parts of the world.

So when you come from my part of the world, you have the evidence of this aggressive melting of the ice all around you. I often say that the ice does not have a political viewpoint. It simply melts.

Q: What does that mean for the people of Iceland in the future?

A: The consequence for Iceland is related to what will happen all over the world. In the 1970s, American scientists and others discovered what is called the global conveyor belt of ocean currents. These huge ocean currents go all around the globe.

And they have a great impact on the weather systems and the climate on every continent on the planet.

The motor that drives this entire global conveyor belt is around Iceland, and it consists of the Gulf Stream coming up from the Gulf of Mexico, bringing warm, salty sea water up to my part of the world, and then the melting of the ice in Greenland brings

fresh water into the oceans around Iceland. So the mix of the Gulf Stream from Mexico and the melting of the glacial ice water is the chemical combination that drives the conveyor belt of ocean currents.

And with the increasing melting of the Greenland ice sheet, this chemical composition is changing. So it will slow down, which will mean colder winters, more extreme weather. It will in fact have a big impact not just on Iceland but on Britain, on Northern

Europe, as well as every other part of the world that is effected by this huge conveyor belt of oceans currents.

Q: Iceland is the only country to derive 100 percent of both its electricity and heating from renewable sources. How can Iceland be a model for the rest of the world?

A: If you go back to the early decades of my life, over 80 percent of Iceland’s energy came from imported oil and coal. If you told people then that we could reach 100 percent clean energy, I don’t think any of us would have believed

it. But we gradually executed this change from the bottom up, fundamentally because it was good business. It made great economic sense. And then in the last 10 or 15 years, during my presidency, we then took this model to other countries.

It is a common but highly misleading notion that there are only few places on the planet like Iceland that can have geothermal power. The United States, China and many other countries have huge geothermal potentials. We have been cooperating for more

than 10 years with the largest energy company in China, Sinopec, in building urban geothermal heating systems in Chinese cities, closing down the coal power stations. An MIT study from a few years ago estimated that the geothermal potential of the

United States, giving present technology, is twice the total energy needs at present of the country. So it’s not just the sun or the wind. It’s also the enormous heat that is under every house, every village, every town, every city, every

region on the planet.

Q: How is the Lui-Walton Fellowship helping in the work that you do?

A: The Lui-Walton Fellowship creates a link between the work I have begun with the Arctic Circle, which has become the largest annual international gathering on the Arctic, and the work of Conservation International and its partners. It’s

a way to take people like me who have gathered experience and contacts and insight throughout their career and to make that useful in a new way. We are now seeing a new model of constructive political cooperation emerging.

The old model consisted of simply leaving it to the governments and the formal negotiators and the big institutions to deal with the challenges and provide the solutions. But that model is very slow and to some extent broken. So what we need to do is

to bring into existence a new model where organizations like Conservation International and individuals like me come together in a dynamic constructive cooperation aimed at executing change quickly and in a comprehensive way. And I think the Fellowship

is an interesting contribution to the evolution of this model.

Q: Coming out of the December U.N. climate talks in Marrakech, you helped author the Roadmap. What does the Roadmap call for?

A: The Roadmap is a new attempt in activating a global coalition in order to execute the promise of the Paris climate agreement. Of course, the results of Paris were important, but if they are not implemented, they will simply be a dream or a vision.

The climate and clean-energy movement has never had such a simple text as the roadmap — one that both moves your heart as well as lists concrete steps that can be executed in a systematic way, whether by individuals, towns, cities, countries,

corporations or others. It’s about action. Not just action by whoever occupies the White House, but the actions by everyone, wherever they are on the planet.

Q: How do you think that governments can best aid in mobilizing private players and the public to take action against climate change?

A: Of course, governments can do many positive, constructive things. But the beauty of the new model of international transformation as well as national success, is that it can be achieved even without the government taking a part. We now have

the tools, through information technology as well as mass mobilization and the different techniques in clean energy. The big government programs that were necessary 30, 40, 50 years ago are no longer necessary in order to execute this change. We can

do it in our own homes, in our town, in our city. We no longer have to wait for Washington or Paris or London to take the lead. And having served as president for 20 years, it is perhaps paradoxical that I should say that presidents are no longer

necessary in order to bring about this positive change.

Q: What hope do you have for collective action on climate change in today’s political climate?

A: You might know that my country suffered hugely in the financial crisis when the banks collapsed in 2008, and it led to monumental social upheaval and protest. None of these were created in the old way of political parties or trade unions or

big organizations. They were instant phenomena created by young students or workers or friends who got together and then mobilized through this new information technology. That was the first time, almost 10 years ago, that I realized that there were

now forces at play, positive forces, that allowed individuals to become more relevant than the president or the prime minister or even the parliament.

Although legislation is still important, presidents are still important, they are no longer necessary in order to execute constructive global change. We already have the tools in our hands and the knowledge. Realize you have the tools in your hands. And

don’t operate the excuse that what happened in one election somehow paralyzes our possibility of acting.

A Distinguished Fellow through Conservation International’s new Lui-Walton Innovators Fellowship, Ólafur Grímsson served as President of Iceland from 1996 to 2016, during which time he made renewable energy and climate change key areas of focus. In 2013, he announced the formation of the Arctic Circle, a non-proft organization designed to address issues facing the Arctic as a result of climate change and melting sea ice.

Jamey Anderson is a senior writer for Conservation International.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Donate to Conservation International.

Cover image: Hikers under the northern lights in Iceland. (© Powerofforever)

Further reading