A steep sell-off in Japan’s yen risks dividing policymakers in Tokyo on whether to embrace a weaker currency or push back against it, raising the stakes ahead of this week’s Bank of Japan meeting.

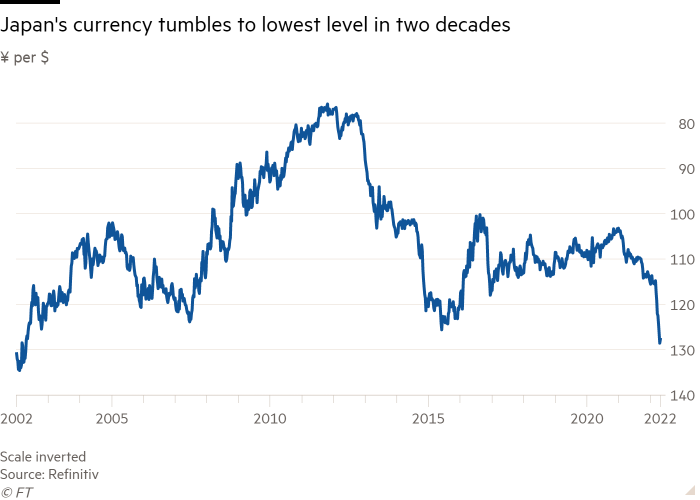

The yen has tumbled more than 11 per cent in less than two months to hit a 20-year low of nearly ¥130 against the dollar, as traders bet on an expanding gulf in monetary policy between the Bank of Japan and other major central banks that are rapidly removing stimulus measures. BoJ officials have shown no sign of deviating from their ultra-loose monetary policy ahead of a meeting on Thursday even as a worldwide surge in energy prices begins to generate some elusive inflation in Japan.

At the same time, the pace of the yen’s tumble — which included a record-breaking 13-day losing streak — has sparked growing speculation that Japan’s finance ministry will order the central bank to intervene in markets to prop up the currency for the first time since 1998.

The unease over the yen’s slide marks a shift from economic policy under former prime minister Shinzo Abe, whose “Abenomics” encouraged currency weakness as a boon to Japan’s export-focused economy.

“The Ministry of Finance won’t want to see the kind of panicky move we normally associate with emerging market currencies,” said Jane Foley, head of currency strategy at Rabobank. “We had a long period when everyone wanted a weak exchange rate because there was no inflation out there. Now it’s politically difficult to just sit there and do nothing when the cost of living is rising, even for Japan where inflation is still relatively modest.”

In the early stages of the decline, Japanese authorities stressed its benefits, including a boost to the profits of the large exporters often seen as the engine of Japan’s economy. But as the yen approaches the ¥130 level, at least one influential survey of business leaders has called those advantages into question.

Larger companies generally favour a weaker yen, which boosts their profits earned overseas. But importers typically see it as a negative, particularly the smaller groups which employ the overwhelming majority of the Japanese workforce.

With the yen now flirting with levels that provoked intervention in the late 1990s and in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis, “the risk of the BoJ entering the market on behalf of the MoF has risen significantly”, said Goldman Sachs FX strategist Zach Pandl, who noted the tone of recent comments from Japanese policymakers.

One reason that the yen is followed closely around the world is its usage in so-called ‘carry’ trades. Japan’s long experiment with ultra-loose monetary policy has allowed investors to borrow in the Japanese currency, in order to seek out assets that offer higher returns elsewhere.

Still, most analysts reckon market intervention would have at best a fleeting impact as long as the BoJ sticks with its so-called ‘yield curve control’, under which it pledges to buy unlimited quantities of Japanese government debt in order to hold 10-year borrowing costs below 0.25 per cent. This policy has caused the gap between Japan’s long-term borrowing costs and those in the US and Europe to balloon, piling pressure on the yen as the BoJ stands more or less alone in resisting a global debt sell-off.

“Any sort of FX intervention — verbal or otherwise — is unlikely to be effective unless and until the BoJ gives up on yield curve control,” said George Saravelos, global head of foreign exchange research at Deutsche Bank. “Either Japanese government bond yields will have to go up or the yen stays weak: Japan can’t have it both ways.”

In the course of its downward move from ¥114 to the dollar in early March, the yen has crossed a number of supposed ‘lines in the sand’ — levels at which market participants had previously imagined would draw some form of intervention from the Japanese authorities. But even when minister of finance Shunichi Suzuki and the BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda have shifted their position to warn of the negative effects of rapid yen depreciation, the market has largely ignored that attempt at verbal intervention.

With little indication of an imminent shift in monetary policy, some analysts expect the yen’s decline to deepen. Jonas Goltermann, senior markets economist at Capital Economics, said the high probability that the BoJ maintains its current stance implies a further percentage point widening in the US-10-year bond yield gap over the next six to 12 months, and a move to ¥140 by the end of 2022.

Mansoor Mohi-uddin, chief economist at the Bank of Singapore, said the concerns over the effectiveness of previous interventions were a factor and the Japanese authorities were likely to ratchet the verbal intervention if the yen weakens beyond ¥130.

“There isn’t the sense of panic that there was in 1998. It’s clearly a devaluation of the yen, but a fairly orderly one,” said Mohi-uddin, adding that it was unlikely that Kuroda at the BoJ would make any change in policy this Thursday given the possibility that Japan could finally achieve the 2 per cert inflation target that has defined his time as governor.

“It’s Kuroda’s last chance, and Japan’s once in a generation chance to get inflation up,” he said. “If they get inflation expectations embedded again then in theory you get Japan back to being the kind of economy it hasn’t been for 30 years.”