What kinds of shorebirds can you find in the United States?

Shorebirds are incredibly lively and exciting! Their showy mating displays and fierce defense of their territory make them fun to watch and observe.

Below, you will find pictures and descriptions of common shorebirds in the United States. I’ve also included some fun facts about each species. I think you will be surprised to learn that a few species of shorebirds don’t live by the shore!

Unfortunately, shorebirds can be hard to identify. First, many species look similar to each other. In addition, due to their migratory nature, they can show up in places they typically don’t visit. That said, you may want to consider purchasing the book below if you need additional help with shorebird identification.

Here are 20 COMMON Shorebirds In the United States!

#1. Semipalmated Plover

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults are brown above and white below, with one black band on the breast.

- The legs and bill are orange, and the bill has a black tip.

During migration, semipalmated plovers are often seen in various open habitats. They’ll visit sandy beaches, golf courses, and salt marshes. They breed in the north, typically close to bodies of water. Occasionally, they’ll nest in a developed area like a rooftop, gravel runway, or even inside an open building.

In the breeding season, males arrive at the nesting grounds first and begin display flights over territories. When females arrive, they engage in courtship displays. Then the female will select a breeding location. Once bonded, pairs stay together for several years.

Semipalmated Plovers forage on foot. They pause to listen and look for prey, then run a few steps to peck at the ground. Sometimes you can spot them holding one foot forward and shuffling it over the sand or mud to startle creatures into moving. They will wade into the water but rarely more than an inch deep.

In the late 19th century, the population of Semipalmated Plovers declined steeply due to overhunting but has since recovered. Despite this return, hundreds of thousands of Semipalmated Plovers are hunted in South America yearly. They also face threats from oil spills and climate change.

#2. Killdeer

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults are brownish-tan on top and white below, with two black bands on the neck.

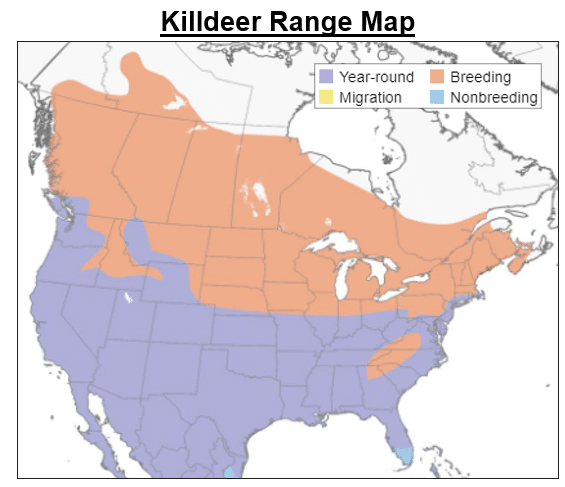

Unlike most shorebirds in the United States, Killdeer occupy dry habitats.

These birds feed primarily on small invertebrates, including earthworms, snails, and aquatic insect larvae. They also follow farm equipment, retrieving unearthed worms and insects. Killdeers are adept swimmers, even in swift water, despite spending most time foraging on land.

During the nesting season, the Killdeer is one of the best-known practitioners of the “broken-wing” display. They will feign an injury and attempt to lure predators away from their nest. They also puff up and charge at intruders such as cows to prevent them from crushing their eggs.

While rooftops attract nesting Killdeer, they can sometimes be problematic for the young. Chicks are often scared to leave the nest because of the high drop! Parents eventually lure chicks off the roof, but it can be dangerous. However, one set of chicks is known to have survived a leap off a seven-story building.

#3. Black-necked Stilt

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults are black above and white below with needle-like bills and rosy pink legs.

These delicate-looking birds favor open habitats with limited vegetation and shallow water. You may spot them in mudflats, grassy marshes, shallow lakes, and sewage or retaining ponds.

Like many shorebirds in the United States, Black-necked Stilts forage by wading in shallow waters. They typically grab food off the water’s surface with their bill. You might also see them catch flying insects or chase small fish into the shallows.

Nesting stilts may form a ring around an approaching predator, calling loudly, flapping their wings, and leaping up and down in what researchers call a “popcorn display.” They’ll even do this to humans who get too close! This species is also known to strike approaching humans from behind with their legs.

#4. American Avocet

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding adults have a rusty head and neck that turns grayish white after breeding.

- They have black and white wings, a white body, and bluish-gray legs.

These shorebirds spend most of their time in the United States foraging in shallow fresh and saltwater wetlands. These unique birds use a signature feeding style called “scything.” They sweep their slightly open bill from side to side as they walk forward, capturing prey in the water.

American Avocets have an incredible way to defend their territory. In response to predators, the American Avocet simulates the Doppler effect by giving a series of call notes that gradually rise in pitch. As a result, intruders are tricked into thinking the bird is approaching much faster than it is.

American Avocets have been known to practice “brood-parasitism.” They lay their eggs in the nests of other Avocets or species such as Mew-Gulls. Interestingly, Common Terns and Black-necked Stilts may parasitize Avocet nests, and the Avocets will raise the other species as their own.

American Avocets face the greatest threat from pollution. For example, in the western U.S., selenium leaching from the soil after rain causes low reproductive success and embryo deformities. Chicks are also susceptible to bird defects from Methylmercury, a pollutant from burning coal.

#5. Greater Yellowlegs

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding adults have a dense, dark checkerboard pattern on the breast and neck that fades after breeding.

- All adults have bright yellow legs.

Greater Yellowlegs occupy various fresh and brackish wetlands in the United States. They typically prefer areas with many small lakes and ponds, scattered shrubs, and small trees, including dwarf birch, pine, and willow.

These shorebirds have a boisterous mating display! They land, run around the female, and pose with upraised wings. Once breeding occurs, both parents tend to the young and noisily fend off predators.

#6. Lesser Yellowlegs

Identifying Characteristics:

- Coloration is grayish brown with fine gray streaking across the head and neck, white eye-rings, and white spots on the back and wings.

- They have vivid yellow legs.

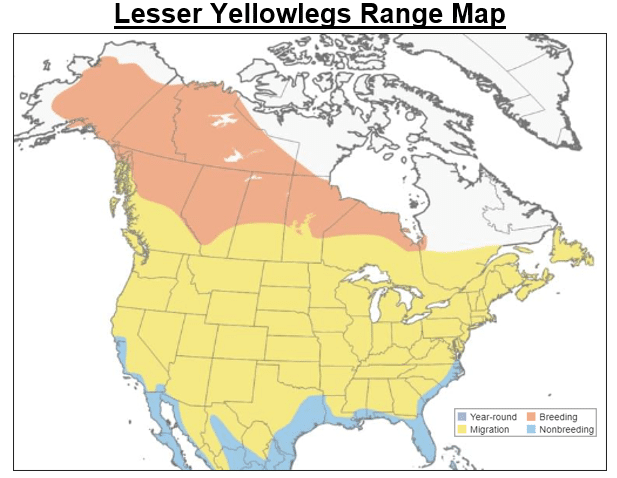

Despite the Lesser Yellowlegs’ similar appearance to Greater Yellowlegs, they aren’t close relatives. Instead, lesser Yellowlegs are more closely related to other types of shorebirds in the United States.

These birds travel in loose flocks and are often seen with other shorebird species during migration and winter. However, they become extremely territorial during the breeding season and will chase intruders away. Lesser Yellowlegs are well known for their noisy defense of nests and chicks.

Lesser Yellowlegs are listed on the Yellow Watch List by Partners in Flight. In the early 20th century, they were heavily hunted in North America. While this practice has ended thanks to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, hunting Lesser Yellowlegs is still common in parts of the Caribbean. They’re also heavily impacted by the continued loss of wetland habitat in their wintering range.

#7. Spotted Sandpiper

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults have a grayish-brown back, plain white breast, and pale yellow bill in winter.

- Breeding adults develop dark brown speckles all over their bodies.

Spotted Sandpipers are active foragers and have a distinctive hunting style. They walk in meandering paths, suddenly darting at prey such as insects and small crabs. They bob their tail ends in a smooth motion almost constantly.

Unlike most shorebirds in the United States, female Spotted Sandpipers perform courtship displays and defend territories.

Females are sometimes polyandrous and mate with more than one male. The males will form their own smaller territories within the female’s territory and defend them from one another.

While it is still a common species, Spotted Sandpiper populations have declined in the last several decades. The decline is primarily caused by compromised water quality due to herbicides, pesticides, and other run-off pollution.

#8. Willet

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults are mottled gray, brown, and black in the summer and a more consistent plain gray in the winter.

- They have bluish-gray legs.

Willets are often seen in coastal areas, with populations differing slightly in ecology, shape, and calls. They inhabit open beaches, bays, and rocky coastal zones.

Willets return to their breeding grounds in the spring, making a characteristic “pill-will-willet” call in flight.

Historically, Willets were over-hunted for food until the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. Today they are threatened by the conversion of native grasslands and wetlands to agricultural areas and coastal development. In addition, adult and fledgling Willets are susceptible to collisions with power lines in their wetland nesting areas.

#9. Ruddy Turnstone

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding males have a chestnut and black pattern on the back, similar to a calico cat.

- They have orange legs, which are brighter during the breeding season.

Ruddy Turnstones occupy different habitats each season. They nest along rocky coasts in the High Arctic during the breeding season. While migrating, they visit plowed fields and shorelines of lakes. Finally, they congregate on rocky shorelines and beaches in the winter.

These beautiful shorebirds have a unique feeding style that earned them their name. They insert their bills under stones, shells, and other objects, flipping them over to find food underneath. Several Ruddy Turnstones may work together to flip a large object.

They will also probe under seaweed and other debris. Their low center of gravity and special feet with short, sharply curved toenails allow them to easily walk on wet and slippery rocks. WATCH BELOW!

#10. Dunlin

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding adults have rusty backs and crowns, black belly patches, and white underparts.

- Non-breeding adults have brown upper parts, heads, and breasts and are pale below.

During winter and migration season, Dunlins roost in coastal habitats. You’re most likely to spot them on mudflats. In addition, they visit inland areas like lakeshores, sewage ponds, and flooded fields to forage.

Dunlins forage by picking up items from the surface or probing the mud with their bills. Sometimes, this species makes a “stitching” motion, probing the ground several times per second. Additionally, their ability to forage at night allows them to take advantage of tide cycles, grabbing prey usually covered by the surf.

Some estimates show that Dunlin populations in North America have declined more than 30% since 2006. The Audubon Society also notes that their populations have noticeably declined since the 1970s, though the reason is unknown. Destruction of wintering habitat could play a role.

#11. Least Sandpiper

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults have brown upper parts and white underparts.

- They have black bills and yellowish-green legs often covered in mud.

The Least Sandpiper is the smallest shorebird in the United States!

During migration, you can spot them in coastal and inland habitats. Eastern populations of Least Sandpiper are believed to migrate up to 2,500 miles non-stop to their wintering habitats in South America.

During the breeding season, males display for the females with noisy calls and fast circular flights that end in dives. While displaying, males will aggressively defend a display territory but become less aggressive once paired.

Both parents tend their young for a while, but the females depart earlier, sometimes before the eggs hatch. Males stay at least until the chicks can fly.

#12. Sanderling

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding adults are spangled black, white, and rich rufous on the head, neck, and back while non-breeding adults are pale overall.

- They have black legs, bills, and eyes.

The Sanderling is one of the most widespread shorebirds in the United States. Predominately a coastal species, you will likely see Sanderlings on wave-washed beaches and rocky shorelines. However, they may occasionally visit inland lakeshores during migration. In addition, non-breeding Sanderlings may remain in their winter habitat year-round.

These shorebirds appear to chase the waves when foraging. As a wave recedes, they run down the beach to find sand crabs and other invertebrates stranded by the wave. They may also probe the sand with their bill for hidden prey. After foraging, Sanderlings often regurgitate sand pellets, mollusk fragments, and crustacean shells.

#13. Long-Billed Dowitcher

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding adults have black, gold, rufous, and white upper parts with reddish underparts, while non-breeding adults are grayish above with a pale belly.

- Females have a longer bill.

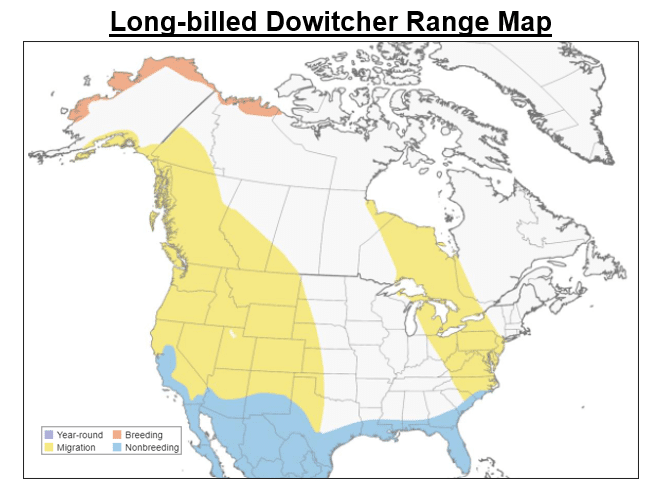

Long-billed Dowitchers are typically found in freshwater environments in coastal areas. They’ll visit lakes, flooded fields, and sewage ponds. They prefer foraging areas with muddy substrate and water less than 3 inches deep.

These birds forage by wading in shallow water or walking on wet mud, slowly and deliberately moving forward and probing deeply into the mud with their bill. Their bills have tactile receptors called Herbst corpuscles, allowing the birds to locate prey by touch. In addition, they often feed in darkness and have excellent night vision.

Due to their remote breeding range, little information is available on the populations of Long-Billed Dowitchers. Partners in Flight lists them as a species of low conservation concern. However, Long-Billed Dowitchers may be threatened by the loss of wetland habitat, climate change, and pollution.

#14. Short-Billed Dowitcher

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding adults have brown, black, and gold upperparts with pale and orange, dark speckled underparts.

- Non-breeding adults are plain, grayish brown above and pale below, with some speckling on the breast and sides.

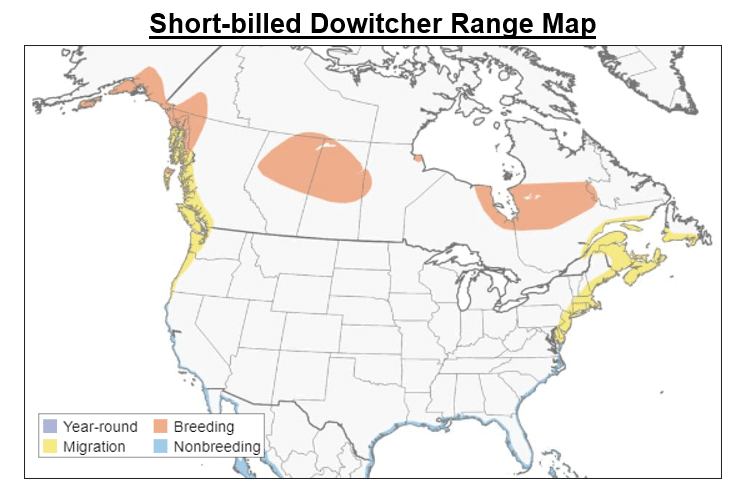

Wintering Short-billed Dowitchers are predominantly found in saltwater and brackish habitats. However, you may spot them on estuaries, lagoons, mangrove swamps, and manufactured ponds for shrimp farming.

Unlike most shorebirds in the United States, this species migrates in stages.

First, they leave their breeding grounds without molting. Then they stop at intermediate locations to complete their molt. Finally, they migrate to wintering grounds when their winter plumage is in. This is a strategy known as “molt migration.”

Short-billed Dowitchers move slowly and deliberately while feeding. They stand still, then walk forward in shallow water or on soft mud and probe their bills deep into the mud. This species is docile and shows little aggression towards other birds while feeding.

#15. Wilson’s Snipe

Identifying Characteristics:

- They are intricately patterned in buff and brown stripes with a white belly.

Wilson’s Snipes are stocky thanks to their extra-large pectoral muscles that make up nearly a quarter of their weight, which is the highest percentage of any shorebird in the United States. Their extra muscle means they can reach incredible speeds in flight, up to 60 miles per hour. Their fast, erratic flights make them difficult targets for predators.

These birds prefer wet, marshy habitats. You may spot them in bogs and flooded agricultural fields during winter and migration. They tend to avoid areas with high, dense vegetation.

Wilson’s Snipes are well known for their dramatic courtship displays. Typically males but sometimes females circle and dive over their breeding territory, and the air rushing over their outspread tail feathers creates a haunting, whirring “hu-hu-hu” sound. They may complete this display for courtship, advertising and defending territory, or warding off potential predators. WATCH BELOW!

Predators have difficulty sneaking up on Wilson’s Snipes because these birds’ eyes are set so far back on their heads. As a result, they can see almost as well behind them as they can to the front and sides!

#16. American Woodcock

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults are mottled brown, black, buff, and gray-brown.

- The face is buff with a blackish crown.

American Woodcocks are also known as Timberdoodles, Labrador Twisters, Night Partridges, and Bog Suckers. They occupy habitats with a mix of forests and open fields and spend their days in forests with moist soil. However, they often spend their nights in clearings such as abandoned farm fields, open swamp edges, pastures, and forest openings.

Woodcocks have a sensitive and flexible bill that allows them to find prey by touch. Sometimes they’re observed performing an odd rocking motion while standing. The vibration from this motion disturbs earthworms to make them easier to find. Researchers believe American Woodcocks may be able to hear prey moving underground.

Outside breeding and nesting season, American Woodcocks are usually solitary though they may group into clusters of 2 to 4 individuals. Surprisingly, the oldest American Woodcock recorded was 11 years and 4 months old.

#17. Wilson’s Phalarope

Identifying Characteristics:

- The coloration is grayish with cinnamon highlights.

- Breeding females are more colorful than males, while non-breeding adults are pale gray above and white below.

Wilson’s Phalaropes are very social throughout the year, nesting in small colonies and traveling in large flocks. You can spot them at salty lakes during migration, but they may also visit sewage treatment plants, ponds, and coastal marshes. They prefer to breed in areas with shallow freshwater like marshes, wetlands, and roadside ditches.

Wilson’s and other phalarope species have a polyandrous mating system where the females typically mate with multiple males. Females may vie for males with aggressive posturing that sometimes leads to fights. Females also perform courtship displays. Once paired, the female lays a clutch of eggs and then abandons the male to seek out another.

These shorebirds have a tremendous appetite and are known to eat so much that they sometimes double their body weight. Occasionally they get so fat they can’t even fly, and researchers can catch them by hand!

#18. Black-bellied Plover

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding males have eye-catching checkered upper wings and a black mask that extends down the belly.

- Non-breeding adults are pale gray above and whitish below.

Black-bellied Plovers live primarily in coastal areas on open sandy beaches and tidal flats during the winter. However, when their preferred foraging locations are underwater at high tide, they go inland to agricultural fields.

Black-bellied Plovers primarily feed on marine organisms and occasionally small fish. Before migrating, they may also eat ripe berries, seeds, and small amounts of sand or gravel. During migration, they feed on insect larvae and earthworms, cutworms, crickets, and grasshoppers.

Black-bellied Plovers are particularly wary and incredibly quick to sound alarm calls. In fact, they act as a sentinel for other shorebirds in the United States, as many species congregating in the same area together will take flight if a Black-bellied Plover sounds an alarm! Their wariness has helped them avoid a population crash due to overhunting that many other shorebird species have experienced.

#19. American Oystercatcher

Identifying Characteristics:

- Adults have a bright orange-red bill, yellow eyes, and red eye-rings.

- The back and wings are brown, the head is black, and the underparts are white.

American Oystercatchers occupy intertidal areas and barrier islands with few or limited predators. They prefer sandy and shelly beaches for nesting. During bad weather events like nor’easters and tropical storms, American Oystercatchers retreat to nearby open habitats such as agricultural fields.

As their name suggests, American Oystercatchers feed almost exclusively on mollusks, including several clams, oysters, and mussels. However, they will occasionally consume other sea creatures if food is scarce.

These specialized birds slowly walk through oyster reefs until they spot a slightly open one. They quickly jab their bill inside and then snip the abductor muscle that closes the two halves of the shell. Parents teach their young this hunting technique during their first year of life.

Surprisingly, oystercatchers don’t always win the battle against shellfish. Occasionally, a shellfish will manage to clamp down tight on an oystercatcher’s bill, which can kill the bird if the tide comes in.

#20. Red Knot

Identifying Characteristics:

- Breeding adults are orange below with a complex pattern of gold, buff, rufous, and black above, while non-breeding adults are brownish-gray above and pale below.

- The bill and legs are dark.

During the migration season and winter, Red Knots use marine habitats. Look for them on sandy beaches, salt marshes, lagoons, and mudflats. They prefer areas with an abundance of invertebrate prey. Occasionally, they visit inland locations, including shorelines of large lakes and freshwater marshes.

A Red Knot’s diet depends on its location. In winter and migration, they feed primarily on marine worms, mollusks, crustaceans, horseshoe crab eggs, and other small invertebrates living in the intertidal zone mud. On nesting grounds, they feed primarily on insects, especially flies.

Sadly, huge numbers of Red Knots were shot during migration in the 1800s. As a result, Partners in Flight have listed Red Knots on the Yellow Watch List, and the IUCN Red List describes them as Near Threatened. Red Knots are highly susceptible to pollution and loss of key food sources at migration stopovers. They’re also expected to be impacted by climate change and sea-level rise. And unfortunately, they’re still widely hunted for food and sport in South America and the Caribbean.

Which of these shorebirds in the United States have you seen before?

Tell us below in the COMMENTS section!