A few years ago FT Alphaville spent a happy day rummaging through the archives of asset management mag Institutional Investor. Even amid the strikingly modern covers, one from March 1969 stuck out.

Featuring a kid’s crayon drawing of “Mr Johnson’s Academy”, the magazine promised to reveal the secrets of the $4.5bn investment firm Fidelity, its founder Edward Johnson II and, his heir-in-making, the “boss’s son” Edward “Ned” Johnson III.

A few weeks ago Ned Johnson passed away, aged 91. Feted as the discreet but de facto king of Boston, he was the head of a family older than the Kennedys, wealthier than Croesus and more private than the NSA.

Charles Ellis, the founder of Greenwich Associates, was one of his many fans. “In an industry where sheer creativity and brilliance really does matter, no one ever doubted that Ned was ever one of the smartest people they ever met in the business,” he told us.

The Institutional Investor feature we stumbled across offers some fascinating clues on how the Johnsons turned Fidelity into one of the world’s biggest financial empires — hardly a foregone conclusion in the 1960s — and how Ned Johnson defied the curse of the boss’s son. But it also starkly highlights just how much the investment industry has evolved in recent decades.

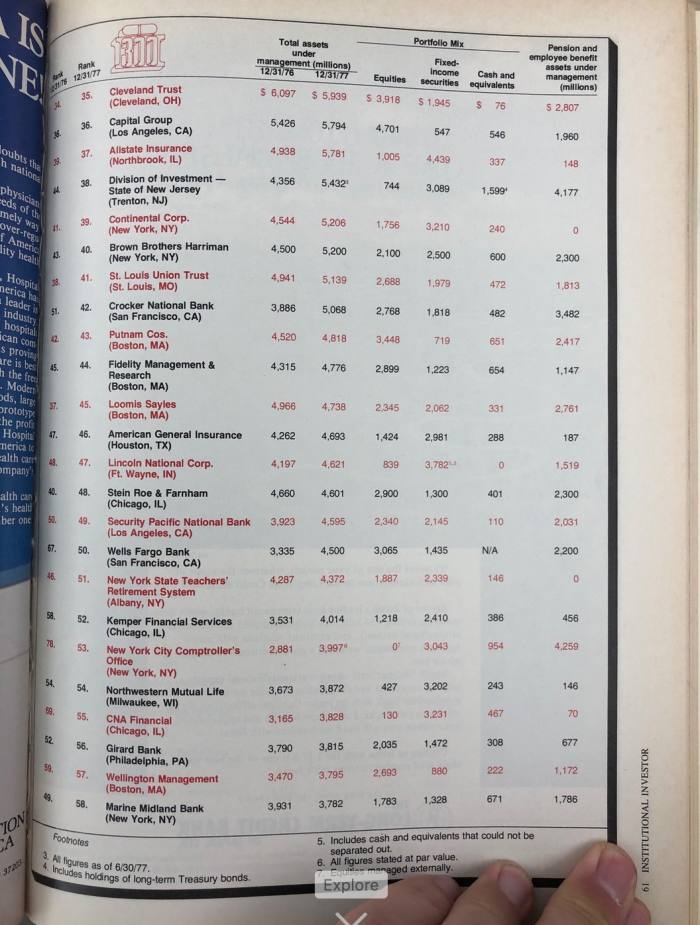

First, the raw data. When Ned Johnson formally picked up the reins as chief executive and chair in 1977, Fidelity had $4.8bn of assets under management. That made them the 44th biggest US investment group, according to a later copy of II we came across.

In other words, Fidelity was a major player but in terms of sheer size it was not even within touching distance of the big bank trust departments, insurance companies, or many direct, “pure” asset management rivals like T. Rowe Price. Even in its hometown of Boston, Fidelity was smaller than the likes of Putnam and MFS.

When Ned Johnson finally retired in 2016, Fidelity managed $2.1tn directly, and was the third-largest US mutual fund group, behind only Capital Group’s American Funds and Vanguard’s fleet of dirt-cheap index funds. Fidelity’s broader “assets under administration” — money on its brokerage platform, for example — had vaulted to $5.7tn.

So how did it happen?

Some of the credit must go to the patriarch. Born into a wealthy New England Family, Edward Crosby Johnson II started dabbling in the stock market in 1924, established the Fidelity Fund in the 1930s, and founded Fidelity Management and Research in 1946.

Back in 1969, Institutional Investor’s senior editor Heidi Fiske described him as a “spare, sprightly, 71-year old Boston lawyer of enormous but restrained energy and a boyish delight in ideas”. Here is how the magazine opened its feature:

Images is a difficult quality to define, but whatever it is, Fidelity has it. Its funds do not make up the largest pool of mutual fund capital, although at $4.5bn Fidelity is one of the most major of the majors. And while Fidelity’s funds have creditable long-term track records, it is not those records alone that are responsible for the Fidelity image. Perhaps one of the factors in the Fidelity image comes from the way Fidelity people — past and present — speak of it, as if it were not merely a money-managing organisation but some kind of academy for self-realisation.

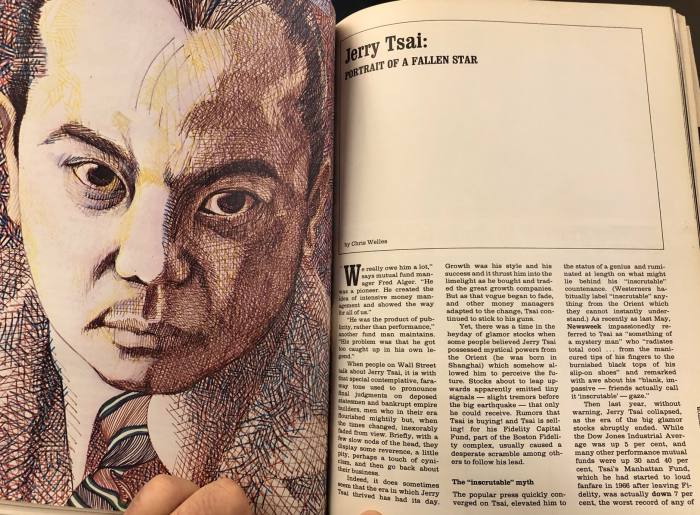

He built an organisation that sought out, nurtured and harnessed brilliant individualists, even bragging to the magazine that “I love primadonnas”. Fidelity’s first huge growth spurt came in the 1960s thanks to one of those hires: Gerald Tsai, arguably the first ever superstar mutual fund manager.

Tsai employed an aggressive, momentum and growth-oriented strategy with the Fidelity Capital Fund. This minted money in the 1960s bull market, where “Nifty Fifty” stocks like Xerox, Kodak and IBM were the FANGs of the era. It ended, however, as bubbles do. Here is a snapshot of a later II profile after the fund’s performance had fallen back to earth.

Nonetheless, despite the mainstream fame of Tsai, Fidelity was seen as a company built in the image of one man. “Fidelity is the lengthened shadow of Mr Johnson,” one Wall Streeter declared to Institutional Investor.

Imagine how hard it must have been for Ned to follow him. After all, many have caved under the pressure of running the family business. Successful generational handovers in investment management — where the main resource is talent that frequently walks out the door — are even rarer.

It helped that Ned Johnson was an adept investor himself, having first managed the Fidelity Trend Fund and later the Fidelity Magellan Fund. Yet it was still far from certain that the then-47-year old would successfully steer the company his father had founded and run for three decades, let alone transform it into an industry juggernaut.

That he did so probably comes down to just a handful of big decisions.

The first was his choice on who would succeed him as manager of the Magellan fund when he took over as CEO and chair in 1977. He selected Peter Lynch, who first joined Fidelity as an intern after caddying for some of the company’s senior executives.

Lynch would go on to notch up one of the most fabulous streaks of returns in investment history. In the 1980s and 1990s he become the public face of Fidelity just like Tsai had done decades earlier, bringing his signature style of picking “understandable stocks” to America’s Main Street:

Ned Johnson was also unusually innovative for a big fund house CEO. He bet big on money market funds in an era of high interest rates, and let investors write cheques against their money-market account. He introduced a toll-free sales number, and advertised heavily. He embraced the birth of Individual Retirement Accounts, which became one of the biggest money funnels in the history of the US asset management industry.

He was also cut-throat. Ellis recalls hearing from Johnson that when he first took over as new CEO he gathered a bunch of the company’s top executives — people that he was personally close to — and told them that within a year they needed to find employment elsewhere. New blood was needed to transform Fidelity from a mid-sized company into a big one, Johnson felt.

This pragmatism was married to enormous inquisitiveness. Like his father, Johnson was fascinated by Asia, and became particularly taken with the Japanese concept of Kaizen, or continual improvement, which Fidelity veterans say is still a thing at the company.

However, what had propelled Fidelity’s growth more recently would be an anathema to Ned Johnson.

At the end of 2021, Fidelity’s assets under management had climbed to $4.5tn — making it the third largest asset manager in the world — thanks largely to breakneck growth from passive index funds housed in its $1tn subsidiary Geode.

Ned Johnson started Fidelity’s index funds but it languished under a separate brand, Spartan, and was only fully brought into the Fidelity fold under his daughter and successor, Abigail Johnson.

Her father once famously said that he doubted index funds would ever take off. “I can’t believe that the great mass of investors are going to be satisfied with just receiving average returns. The name of the game is to be the best,” Ned Johnson once told the Boston Globe in the early days of passive investing.

Moreover, Fidelity under Abigail Johnson has started a cautious break with Fidelity’s superstar fund manager culture, and broadened its employer base from the white, male, middle-class, Catholic Red Sox supporters that dominated since its founding.

These moves appear antithetical to the company embodied by the first two Johnsons, and show how much the asset management industry has changed of late. The era of nurturing star investment managers before building them up into household names and watching the money roll in is over.

But perhaps the real secret to Fidelity’s success under the Johnsons dynasty is an under-appreciated ability to adapt. Back in 1969, Edward Johnson II made an oblique reference to the environment he tried to inculcate at Fidelity, which might help explain why his son and granddaughter have proven such disparate yet adept stewards of his legacy.

You want the greatest degree of laissez faire without chaos. Children know you love them and that you’re always there and otherwise you leave them alone and that’s it. That’s the way it is here too, I think.