Just because that plastic item you rinsed out and placed in your recycling bin is labeled as recyclable doesn’t mean it actually is.

In fact, according to a 2020 Greenpeace report, most types of plastics in the U.S. are not recyclable and usually end up in landfills or incinerators, if not polluting the environment. The vast majority of recycling facilities across the country can only accept two types of plastics, the report found, and even then only a small fraction of that plastic waste is actually processed.

How small? According to the Environmental Protection Agency less than 9% of plastic material generated in the U.S. Municipal Solid Waste stream was recycled in 2017 and 2018, the last years for which data is available. Another 15.8% was combusted for energy, while 75.6% was sent to landfills. Millions of tons also ends up in our oceans and rivers each year.

The National Academy of Sciences warned in a recent report that only way to stem the rising tide of plastic is for companies to make less of it and for recycling programs to be retooled so that more of what we throw away can actually be reused.

While recycling “is technically possible for some plastics, little plastic waste is recycled in the United States,” the report said, noting that materials put in plastics to change hardness or color make them too complex to recycle cheaply, compared to making new virgin plastic.

Many of the companies producing the majority of single-use plastic waste in the world have pledged sustainability-related changes in recent years while spending millions in marketing to convince the public that their plastics are recyclable.

“Instead of getting serious about moving away from single-use plastic, corporations are hiding behind the pretense that their throwaway packaging is recyclable,” said John Hocevar, Greenpeace USA oceans campaign director, in a press release announcing the report’s findings. “We know now that this is untrue. The jig is up.”

Howard Hirsch, an attorney with the public interest firm Lexington Law Group which has won plastics-related litigations against several consumer product giants, told NBC that there’s an “overall corporate effort” to make the public feel like they can consume without consequence so long as they throw everything in the recycling bin, regardless of whether it belongs there.

Hirsch pointed to a 2020 investigation by NPR and PBS’s “Frontline,” which found the makers of plastic — the nation’s largest oil companies — lobbied states in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s to mandate the “chasing arrows” symbol appear on all plastics. These petroleum companies and the industries that depend on plastic to bottle their products sold to the public the notion that the majority of plastic could be recycled, despite knowing otherwise and making billions of dollars in the process.

“Growing up, we all learn, ‘Reduce, reuse, recycle.’ And unfortunately, the first two R’s are often skipped over in favor of the third,” Hirsch said.

Only 8.4% of discarded plastic actually goes through the full recycling process to be transformed into other products. The rest ends up in landfills. So how are so many companies still touting their plastic products as recyclable? The New York Times explains.

Plastic resin codes: What those recycling symbols really mean

Most plastic products are imprinted with a number surrounded by a triangle of arrows, known as a resin identification code. Consumers have long assumed if a package contains one of these symbols that item is recyclable, but that’s not the case.

The plastics industry adopted the code in the 1980s as a way to standardize plastics manufacturing. According to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), the numbers are meant to indicate the type of plastic resin used in a product. And while they are not “recycle codes” for consumers, they are an aid to recycling.

There are seven main resin codes:

- Plastic No. 1, which is made of polyethylene terephthalate, or PET;

- Plastic No. 2, which is made of high density polyethylene, or HDPE;

- Plastic No. 3 is polyvinyl chloride, or PVC;

- Plastic No. 4 refers to low density polyethylene, or LDPE;

- Plastic No. 5 means the material is polypropylene, or PP;

- Plastic No. 6 is polystyrene, or PS;

- and Plastic No. 7 is a catch-all category referring to any materials not already listed.

Every county and municipality has a different recycling program, with varying rules and capabilities when it comes to plastics recycling. In most communities, items labeled with the Nos. 4, 6 and 7 will likely end up in landfills because they are difficult to recycle and most recycling programs in the U.S. do not accept them. Those numbers can often be found on plastic bags, Solo cups, styrofoam containers and toys. Plastics with the No. 3 — found on cosmetics packaging, shrink wraps and piping — are not only not recyclable, but their chemical composition can contaminate other batches of plastics.

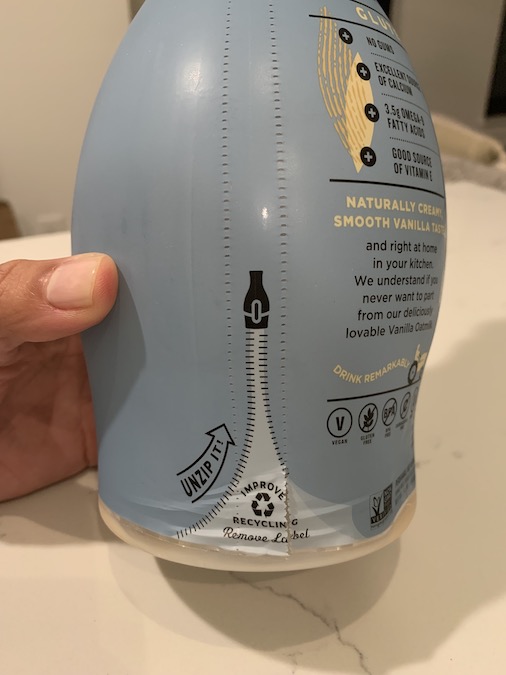

Greenpeace surveyed the nation’s 367 materials recovery facilities and found that only PET No. 1 and HDPE No. 2 plastic bottles and jugs can be legitimately labeled as recyclable in the U.S. since those are the only two types of plastics widely accepted at most sites. However, the report notes that full body shrink sleeves that are added to these plastic products make them non-recyclable if they are not removed for processing.

The shrink sleeve on a bottle of Califa Farms oat milk is pictured with directions to remove to improve recycling. According to the company, the blue plastic wrapping is also recyclable but Califa suggests taking it off for better color sorting.

The Greenpeace report also found that only 14% of facilities surveyed accepted plastic containers frequently used for takeout, 11% accepted plastic cups, about 1% accepted plastic utensils and straws, and none had the ability to process single-use coffee pods.

Nevertheless, at least 30 states still require plastics to be imprinted with the recycling symbol, “creating significant consumer confusion,” said Shannon Crawford, a spokeswoman for the Plastics Industry Association trade group, in testimony against a California law targeting recycling mislabeling.

The California bill, signed into law last year by Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, prohibits the sale and distribution of packaging that makes misleading claims about its recyclability. Senate Bill 343 sets the nation’s strictest standards for which items can display the chasing arrows.

“It shouldn’t be a difficult concept: if it says ‘recyclable,’ that means you should be able to put it in the recycling bin, and if it says ‘compostable,’ you should be able to put it in the composting bin,” said the bill’s author, Democratic Assemblyman Phil Ting. “Somehow companies have decided that they can get away with marketing that they know is deceptive because of the technicality that most things are theoretically recyclable or compostable.”

Industry groups who opposed the law argued the new bill will force companies to either be out of compliance with other state laws that require it or create California-only packaging products.

A coalition of more than 70 groups who support the bill, including the Sierra Club California, said in a joint statement that, “this will encourage producers to make sustainable packaging choices, and support companies looking for a steady supply of material to invest in recycling and reprocessing facilities in California.”

One of the major barriers for recycling is the economics of virgin plastic and subsidization of the fossil fuel industry

Margaret Spring, chief conservation and science officer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium

It’s too expensive to recycle: Bleak market with few buyers

For many Americans, recycling is a single-stream process, meaning plastics, glass, metal and paper all get lumped together in the same bin. The system was widely adopted in the early 1990s as a way to get more Americans to recycle, and took the national recycling rate from 10.1% in 1985 to 28% by the year 2000, according to the EPA.

The convenience of a magic bin made recycling easier for consumers; it also made sorting more difficult and created headaches for processors. If glass breaks in a bale of mixed plastics, for instance, the shards can contaminate that load and it will likely get discarded rather than recycled. Food contamination is another problem.

Of the materials that do end up getting processed, there is still the question of who wants it? That’s because what is and isn’t recyclable depends on what the market is willing to buy and repurpose. If no one wants it, it can’t be recycled. Since 2018, the U.S. has struggled to find a new market for its plastic waste after China stopped importing it.

For nearly two decades, China had been the top buyer of the world’s plastic recyclables, taking in more than 116 million tons of material between 1992 and Dec. 31, 2017, according to a study on the global plastic waste trade. Most of that plastic waste ended up in landfills or incinerated because the bales were largely contaminated and couldn’t be recycled. Beijing’s decision to crack down on imports of American waste led to a collapse in prices for recyclables and left the U.S. recycling industry scrambling to find new markets willing to buy our trash.

“The Chinese were actually paying for this material, so the prices for a lot of these materials plummeted,” said Anne Germain of the trade group National Waste & Recycling Association, in a phone interview with NBC. “And so the ability to have an economically viable recycling program was jeopardized.”

In the year after China’s ban was implemented, local recycling processors began scaling back plastics collection, with many accepting only plastics numbers 1 and 2 because there was “sufficient market demand and domestic reprocessing capacity,” according to Greenpeace’s report. Others started charging residents fees to cover the ballooning costs of their programs. Most, however, moved to dumping recyclables at landfills.

In the small town of Franklin, New Hampshire, the collection of recyclables were halted altogether in the wake of China’s ban, according to the Concord Monitor. Franklin used to sell its mixed recyclables for $20 per ton. After the market collapsed, it was shelling out $129 per ton just to send them to processors. For a community already grappling with budget shortfalls and where 20% of the residents have incomes below the poverty line, the extra cost to recycle became too burdensome.

In Pennsylvania, the City of Erie Department of Public Works informed residents that its vendor could only accept plastic numbers 1 and 2 due to low global market demand for “other plastic items” that “used to be shipped overseas, but are no longer being accepted.” All other plastics, it states in its recycling guide, “should be thrown in the trash.”

Still, only about 29% of recyclable PET plastic bottles and 19% of recyclable HDPE plastic bottles were actually recycled, according to the EPA.

Those numbers underscore a sad reality: Domestic manufacturers and private-sector recycling companies don’t see a financial incentive in plastics recycling.

The process of recycling is usually more expensive than making plastic products from virgin resin. Collecting, sorting, cleaning and preparing used plastics has become more labor intensive, requires more energy and is costly. And because plastics are made largely from oil, with fossil fuel prices fairly low over the years, virgin plastic are more profitable to produce.

“One of the major barriers for recycling is the economics of virgin plastic and subsidization of the fossil fuel industry,” said Margaret Spring, chief conservation and science officer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, and chair for the National Academy of Sciences report.

Most containers are made of a blend of plastics and other chemicals, which can make it harder to isolate a base material that can be recovered and reused. And even plastics that are easier to recycle eventually diminish in value because its quality degrades through the recycling process. From there, the material is generally downcycled to make carpet, plastic lumber or a bench, none of which are further recyclable.

California, in its effort to stem the rising tide of plastics, became the first state to mandate a minimum recycled content standard of 15% for most beverage containers starting in 2022, and increasing to 25% in 2025. The law’s objective is to create domestic demand for recycled resin and in turn, prop up the entire recycling system.

Germain applauded the law, noting that since its passing, the market value for plastics in California has jumped higher than anywhere else in the country.

“We can’t just be pushing material into recycling and hoping that somebody is going to buy it,” Germain said. “We need a buyer for all the materials.”

Making plastic producers pay foot the bill for recycling

One way states are looking to tackle the high cost of disposing the packaging material accumulating around the country is by shifting the responsibility for the waste from municipalities to the producers.

Lawmakers in Maine passed the country’s first “producer responsibility” bill last July, requiring manufactures of products that involve packaging material to pay for the cost of disposing the waste. The fees from these “producer payments” will go into a new state fund that will be used to reimburse municipalities for recycling and waste management costs.

“Right now, taxpayers are paying to manage packaging waste,” said state Rep. Nicole Grohoski, in a phone interview with NBC. “This is going to shift the cost from taxpayers onto the producers of waste, who are the ones that really control the decisions around what packaging is made of and how much packaging there is.”

With the market volatility increasing the cost of running recycling, Grohoski said many municipalities — especially rural ones — are struggling to maintain their programs.

Grohoski said the state has strived to meet a goal of recycling at least half of its waste stream since the 1980s. Because packaging is estimated to account for about 40% of Maine’s waste stream, Grohoski said the bill will help the state meet its long-time recycling goals.

The law aims to incentivize the industry to stop creating excessive or non-environmentally friendly packaging, Grohoski said. Under the legislation, companies can lower payments by using packaging composed of recycled material or without toxins, like PFAS, that are easier to recycle.

Nearly a dozen states — most of them Democratic-leaning — are considering similar legislation, including large influential economies like California and New York. Lawmakers in Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, Washington and Vermont have also introduced producer responsibility bills.

“It’s an opportunity to recognize the problem here at home here in America and be a part of the solution and create a more circular waste management system, rather than shipping it off and hoping for the best,” Grohoski said.

After opening all your Black Friday orders, you can just gather all that packaging on the floor and take it to the recycling bin, right? Not so fast — it’s not that simple. NBCLX’s Fernando Hurtado talked to a recycling expert about exactly what packaging can get recycled, and what is still destined for the landfill.