INDIANAPOLIS — When 19-year-old George Tompkins was found strangled and dead tied to a tree with his hands bound behind his back on March 16, 1922, in Cold Spring Woods in Riverside Park, his death was an embarrassment and political inconvenience to the people who ran Indianapolis.

”That was a political problem,” said Leon Bates, who studies the history of Indianapolis’ African-American community. “It was the kind of thing that if you bring in more business, more people, it’s not popular with everybody. They didn’t want that out there. It’s better in some peoples’ minds just to close the books on it and let it go, and that’s what they did.”

Even though the police officers on the scene and the deputy coroner who first examined the body determined the teenager from Kentucky died of lynching, his cause of death was later listed as suicide.

“Someone changed that death certificate, the official cause of death,” said Bates, referring to the handwritten changes on the Tompkins’ death certificate. “Once they officially did that, all investigations ended.”

Indiana in the 1920s was emerging from World War I, seeking to capitalize on its agrarian economy in the heart of America’s breadbasket. At the same time, Indianapolis was attracting multi-cultural transplants from Europe and the southern United States. Many were drawn to the city’s factories, as large automakers did their work in Marion County.

Just 60 years after the Civil War, it wouldn’t do to have Indianapolis known as a place that would be comfortable with hosting racial intolerance and murder north of the Maison-Dixon Line.

”This was in March of 1922,” said Bates. “The Ku Klux Klan comes to rise to power in June, and it starts to take off, and I think they didn’t want something like this hanging around. They wanted to do away with it and quickly. Indianapolis had other high-profile killings, and if they left the file open for too long, then it became a political problem for the city or the powers to be, so they closed the books on it.”

In the summer of ’22, just a couple months after Tompkins was buried in an unmarked grave in Floral Park Cemetery, D.C. Stephenson came to town and set about taking over the Indiana Statehouse and infiltrating Indianapolis and Marion County government.

”The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana had lots of political sway,” said Bates, who referred to Stephenson’s loose-knit network of quasi-law enforcement officers throughout the state who would dig up dirt and inform on any local officials with criminal corruption exposure who could then be coerced to literally carry the Klan banner in their communities.

Throughout the middle of the decade, Stephenson and the KKK controlled state and Indianapolis politics as the Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan, from a mansion in Irvington, plotted to spread his influence to Washington.

His vicious rape and murder of a young woman, a state employee he stalked and later kidnapped and attacked on a train bound from Union Station to Chicago, resulted in a 31-year prison sentence and the downfall of the Klan in Indiana, only to see the group seek to reassert itself with rallies at the Statehouse and the state Indiana in the 1990s.

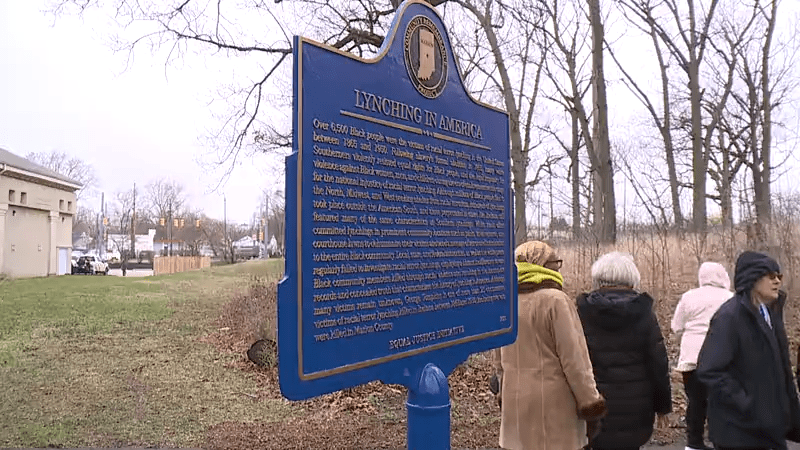

Following the unveiling of a historic marker memorializing Tompkins behind Municipal Gardens on Sunday, Deputy Mayor Judith Thomas said the tribute serves to, ”tell the truth of the City of Indianapolis that there were challenges over 100 years ago and beyond, and we’re overcoming them by talking to each other, collaborating with each other and telling those stories.

”We see in the early part of the last century that there were still racial challenges, things that we didn’t overcome because we weren’t honest with each other, laws that didn’t get changed, prejudices that were still out there, because we didn’t have those hard conversations.

”I think we have to have hard conversations no matter what the laws are, no matter who’s in a position of power, we have to all talk to each other about our challenges that we’re having, communicate with each other, and be honest.”

Tompkins’ grave in Floral Park Cemetery remained unmarked until 2022, when his life and death were uncovered by the Indiana Remembrance Coalition, and the Marion County Coroner issued a revised finding that he died of murder and not suicide.

”George Tompkins deserved better,” Coroner Alfie McGinty told attendees at the unveiling of the marker. “And while we cannot change the past, we can assure that his name is spoken and his story is remembered and his legacy will endure.”