The recent announcement that a “living building” will be constructed at the entrance to Picnic Point struck me as odd. The very phrase “living building” seemed a clever combination of words, softening the idea of brick, mortar and glass with the word “living,” evoking a natural landscape. The building, equipped with innovative technologies meant to lessen environmental harm, would become a visitor and education center — but to me, it seemed contrary to my understanding of a nature preserve.

I had never been to Picnic Point, but it was a must-see, my Wisconsin friends told me. My husband and I retired seven years ago and moved to Madison, drawn by the desire to be closer to family and live in a college town bustling with ideas. We eagerly explored the Ice Age Trail and discovered Wisconsin’s roly-poly beauty. My daughter was married here, and I read Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac during the week before the wedding. It was a daily journey immersed in nature’s stories, infused with love and joy.

The announcement of the living building coincided with research I was doing on the history of cardiac rehabilitation. I’d read that Picnic Point, as part of the Lakeshore Nature Preserve, was where early advocates for exercise brought their patients in the aftermath of heart attacks. A practice that had jumpstarted the development of successful rehabilitation programs for patients with coronary artery disease.

It was time for me to visit Picnic Point.

On one of the first days of spring, bright with sunshine but infused with cool winter air, I parked my car and walked across the street toward the entrance to the trails, navigating bits of salty ice covering the ground. Birdsong came from the thick forest beyond the entrance, merrily colliding with the crunch of my footfall, a call and response not unlike listening to jazz musicians trading musical improvisations: a solemn clarinet calling to the sprightly piano, a drone of the double bass blending with the beat of the drummer’s rhythms.

The entrance was a maze of knee-high fences zigzagging along a sandy path covered in melting snow. A woody, damp, mossy scent filled the air. A strip of trampled weeds was the only dry footpath into a half-frozen grassy area. Picnicking unlikely. The shadow of climate change hovered: Was Picnic Point sinking?

I walked along the soggy limestone path, giving up on finding dry ground. Around the first bend lay sacred burial grounds of Native Americans, marked off by an ankle-high black chain fence. Farther on, several large half-logs, resting on wooden blocks that cradled their roundness, marked a large fire pit. Blackened beer cans and shriveled candy wrappers peeked upward from the ash pile — a winter picnic, I supposed, in full view of this ancient cemetery. Later, I would learn that archaeologists estimated that the evenly arranged mounds I observed were built by Indigenous people more than 2,500 years ago.

In other locations around Wisconsin, burial mounds appear as effigies in the shape of animals and other sacred objects, while on Picnic Point, they are conical, oval and circular. On my visit, the mounds were hard to discern, covered by tangled brush and tall grasses, but I could trace their hazy footprints, astonished that they somehow withstood thousands of years of short-sighted progress.

My meditation collided with the sound of voices. A small crowd of runners leapt over puddles as if playing a game of hopscotch. The birdsong changed its register, as if alarmed, but soon resumed their distinct call and response. Mating season was to begin; new life was on the horizon.

As I walked further, the landform became narrower. The sound of ice breaking along the shoreline punctuated the persistent birdsong. I could almost hear small wavelets brushing alongside the edges of the peninsula, echoing from the left side of the path to right. Change was in the air; winter becoming spring, a favorite season for university students to ponder the end of a school year; some, I imagined, would become engaged serenaded by the sounds of Picnic Point.

When I arrived at the peninsula’s tip, I found a half-log and sat down. Across the vast blue of Lake Mendota, Maple Bluff was a foggy collection of houses and buildings framed by trees with just the first hint of green.

Later I would learn that 19th-century climate observers would row a boat from Picnic Point to Maple Bluff, bringing along a case of beer for friends on the other side of the lake while gathering data that indicated how soon the lake would freeze over. Those figures, now graphed and analyzed, offer a longitudinal look at the impacts of climate change. It seemed heroic, to row a boat in icy waters with the possibility of capsizing. Yet that’s the kind of action that has helped us understand the impact of a warming climate.

When I returned home, I re-read the press release. The living building will be built outside the stone wall on land already disturbed by human intervention. The construction plans include geothermal energy systems, enhanced access for walking and biking, and will not disturb the mounds. It will be a foothold for a sustainable future, a stepping-stone instead of a stumbling block. It feels like a promising idea — a bridge between what has been, what is, and what could be — a place that serves as a gateway to the living story of Picnic Point.

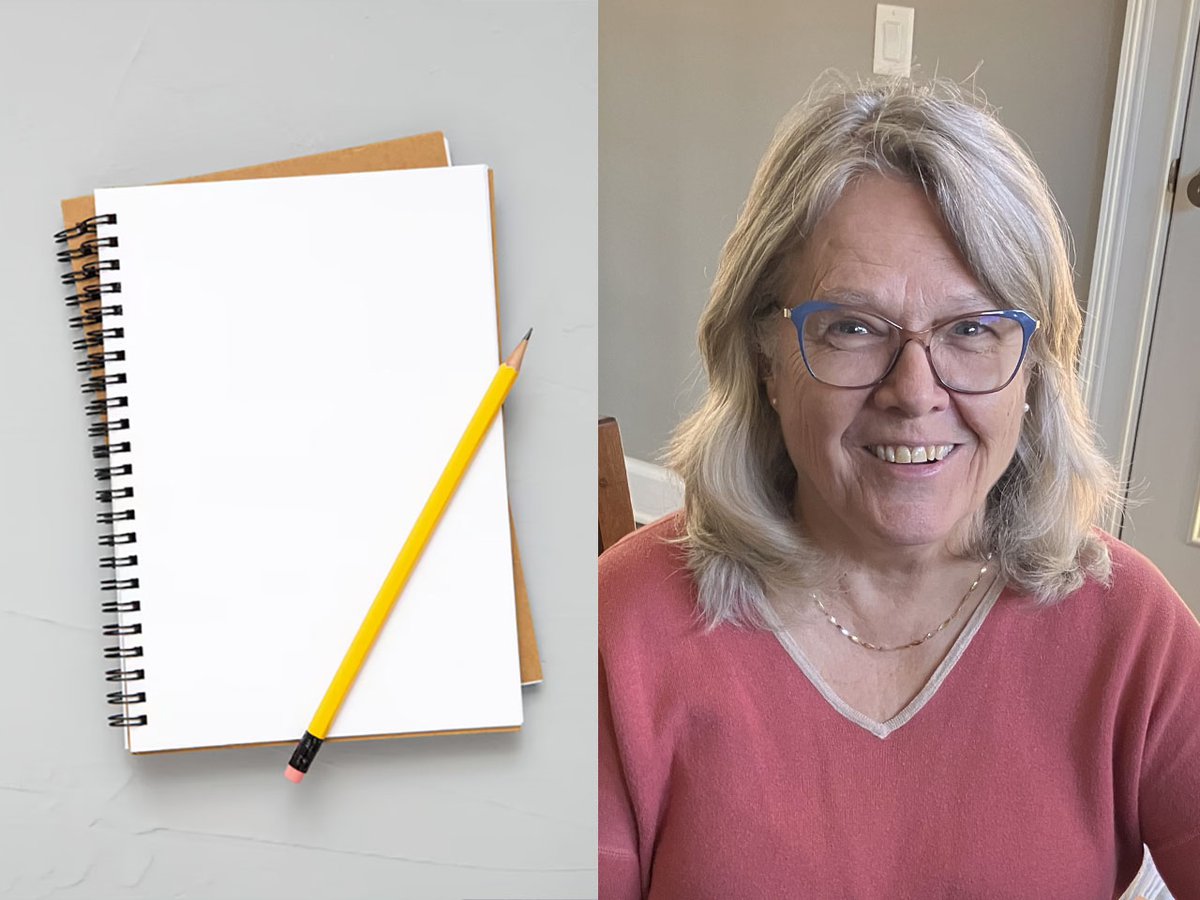

Janice Kehler is a freelance writer with a passion for telling untold stories that connect personal lives with cultural issues.